175 years young: Hobart Shule’s landmark anniversary

Hobart Synagogue is turning 175 years old, but coronavirus restrictions have caused the cancellation of the celebrations. The AJN speaks to key figures at the historic shule.

IT’S not commonplace to celebrate a 175th anniversary, so it was heartrending when COVID-19 restrictions scuttled plans by Hobart Synagogue – consecrated on July 4, 1845 and one of Australia’s oldest surviving synagogues – to mark its milestone in the Apple Isle.

Hobart Synagogue’s president Jeff Schneider tells The AJN the July 3-5 weekend was to have seen services, a concert, tours of historic sites, and a panel discussion. “Our members past and present, descendants of our historic members, several rabbis and members of the greater Australian Jewish community were to be attending.”

But there is a silver lining. Soon after the lockdown began, the Tasmanian State Archives, which holds Hobart Synagogue’s historic records, digitised its meeting minutes back to 1841.

“It was amazing to see these documents in a digital format,” says Schneider, “however, since they were handwritten, it was challenging to read. Given that the virus kept us all at home, we thought there may be some people interested in volunteering to transcribe the meeting minutes”.

“To our surprise, there were several congregation members, descendants who were meant to attend the 175th anniversary, and volunteers from the Australian Jewish Genealogical Society who kindly donated their time to transcribe these documents.”

Schneider says the shule also took advantage of the synagogue’s temporary closure to do restoration work on the building and Jewish cemetery.

Throughout their history, the Van Diemen’s Land colony and the Tasmanian state have welcomed Jews from Czarist pogroms, the Holocaust, apartheid South Africa and Soviet repression. Many Tasmanian Jews are from somewhere else.

Originally from the US, Schneider grew up in a Masorti family in Baltimore. He met his wife Lisa, a Sydneysider, in Washington, DC, and a visit the couple made to Tasmania in 2014 convinced them to move there.

Schneider notes there were Jews in Van Diemen’s Land dating back to the earliest convicts. (There were 233 Jewish convicts in the colony.) In the late 1830s, free-settler merchant Louis Nathan (later Hobart Synagogue’s first president) arrived from Sydney via London. Nathan and his business partner and brother-in-law Samuel Moses set the example of observing Shabbat and rituals, and were generous contributors to the synagogue’s building fund.

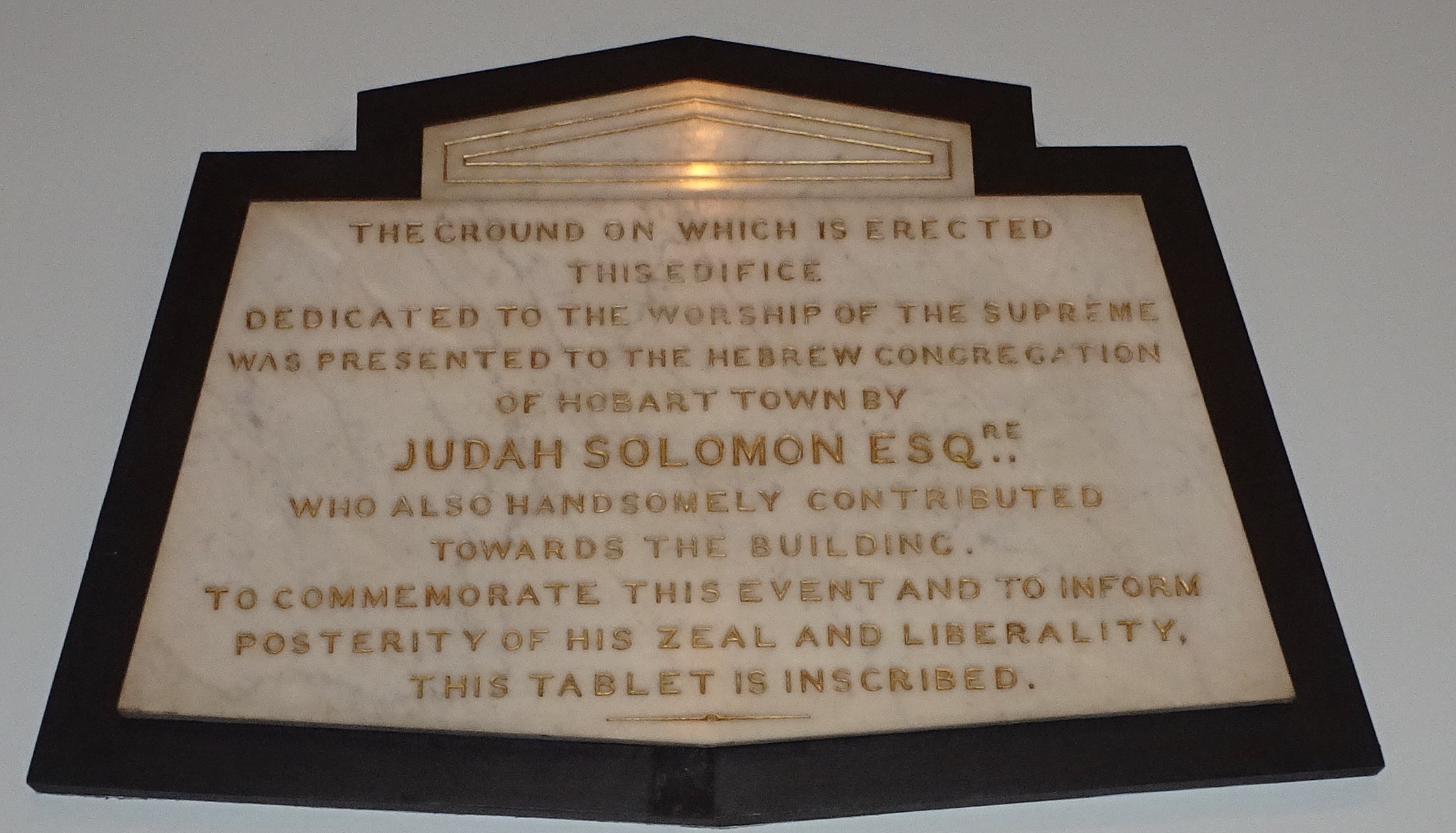

“Prior to the synagogue’s consecration in 1845, services were held in various places in Hobart, including [transported former convict] Judah Solomon’s Georgian Mansion, Temple House, next door to the synagogue, and restored in the 1990s by the Tasmanian government,” recounts Schneider.

A meeting was held in the home of Isaac Friedman, the first Hungarian free settler in Australia, where it was decided to construct a synagogue. Solomon granted the land, and a tender to build the synagogue for 717 pounds was accepted. But as insufficient funds had been raised, an appeal was made to the president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, Sir Moses Montefiore. He responded positively, as did many others in Britain. The overseas interest in the synagogue is reflected in the donation lists on panels near the ladies’ gallery.

Hobart Synagogue was designed by James Alexander Thomson, a Scot transported in 1825 for attempted jewel robbery. Members of the congregation wanted the building finished for the High Holy Days in 1845, but the shule, on Argyle Street in Hobart’s CBD, and constructed in an Egyptian Revival style with a biblical Exodus motif, was completed ahead of time.

“We are proud that despite being a very small community, we have managed to keep Judaism alive in the same building as so many who preceded us have used,” says Schneider.

“In 1848, the Jewish population in Van Diemen’s land was 435, and that was essentially our peak. Starting in the late 19th century, several mentions of our congregation notes the small numbers. In 1918, after our Diamond Jubilee of the laying of the foundation stone, our secretary Nat Edwards wrote that the congregation is ‘probably the smallest congregation in the civilised world’. In 1933, a newspaper article stated that there were ’10 Jewish families’ in Hobart.”

The congregation’s Sifrei Torah are mostly as old as the shule. It has not had a permanent rabbi since the 1950s, notes Schneider [the last one was Reverend George Reuben], “but yet we have managed to keep an active group”.

“These past few years have seen growth and optimism,” says Schneider. “Our membership has seen a flurry of activity as we have welcomed several new families with children. We are taking steps to establish a cheder for the congregation for the first time in decades. Our board of management has a new makeup, with a combination of long-serving and new members that reflect the diversity of our congregation.”

The shule has had support from mainland Jewish communities for decades, and Chabad is very active. Rabbi Raymond Apple, emeritus rabbi of Sydney’s Great Synagogue, recalls to The AJN being invited there as a student convenor of a Jewish children’s correspondence school under Melbourne’s United Jewish Education Board.

He remembers being “taken aback to see people standing up and sitting down while I was speaking, not realising how hard the seats were and being so disconcerted that my sermon came to a hasty end”. In an arrangement believed unique in the world, these timber benches had been used to seat Jewish convicts marched in under arms for prayers.

Hobart Synagogue’s status as a shared shule since the 1980s, hosting alternating Orthodox and Progressive minyans (with the ACT Community the only other shared shule), is now a settled arrangement. But it was still controversial at the time of its 150th anniversary in 1995. Writing later in OzTorah, Rabbi Apple commented, “I upset the women by insisting that they sit separately from the men.”

Rabbi Dr John Levi, emeritus rabbi of Melbourne’s Temple Beth Israel (TBI), has for many years visited on landmark occasions and for some Shabbatot, also addressing Tasmanian organisations and schoolchildren.

He became the shule’s consulting rabbi – an extension of his role as senior rabbi of TBI – from the mid-1960s onwards. First visiting Tasmania on his honeymoon, he still says, “Launceston’s a gem and Hobart’s a diamond.”

In 2003, attending the launch of A Few From Afar, an anthology of Tasmanian Jewry edited by historian Dr Peter Elias, Rabbi Levi made a chance encounter with a curator from the State Library of Tasmania, who mentioned some obscure sheet music in the archives. It turned out to have been written for the shule’s 1845 dedication service. The rabbi assumed the composer was Jewish, but it turned out to be Joseph Reichenberg, a Roman Catholic bandmaster of the Hobart Town Regiment.

Rabbi Levi gave a copy to Joseph Toltz, a cantor at Sydney’s Emanuel Synagogue, who created an arrangement performed in Hobart Synagogue in 2005 at a Shabbat service marking its 160th anniversary. “To find the music from the shule’s opening service is an extraordinary experience,” the rabbi reflects.

Stephen Graetzer, 77, a father of three, has been a congregant of Hobart Synagogue since his youth. His family fled Germany in 1937, arriving in Melbourne, before his father found work in Tasmania. The family moved to Hobart where his father joined the synagogue board.

In the 1980s, Stephen began as treasurer, serving for 28 years. During that time, the shule raised funds to renovate its National Trust-certified premises, hiring an architect who had restored the historic Port Arthur penal settlement.

Graetzer also coordinated the reinterment of Jewish settlers and convicts in the Jewish section of Hobart’s general cemetery after a colonial-era cemetery faced redevelopment.

Recalling the shule’s 150th anniversary celebrations in 1995, he reminisces about “one of the few times I’ve seen the synagogue full”.

But a favourite memory is more small-scale, “I always liked the Friday evening services followed by pot-luck dinners at the homes of various congregants, especially in winter when it was a nicely heated home.”

Graetzer compares Hobart Synagogue’s longevity with the Chanukah oil miracle. “What was meant to last only a day lasted a week. The synagogue here is doing much the same.”

Get The AJN Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

comments