A lesson from a broken letter vav

The Torah is indeed an endless spring gushing forth “mayim chaim” – living waters – that spread in all directions.

It was Mincha time on a wintry Shabbat afternoon. Sitting perusing a chumash after the Sefer Torah had been placed on the bimah ready for reading I suddenly noticed an unusual sight – the sefer was being dressed and taken back to the Aron Kodesh before reading had even begun. I wondered what was happening when a second sefer was brought and opened – and then the baal koreh suddenly loudly expostulated: “This is ridiculous, it also is no good.”

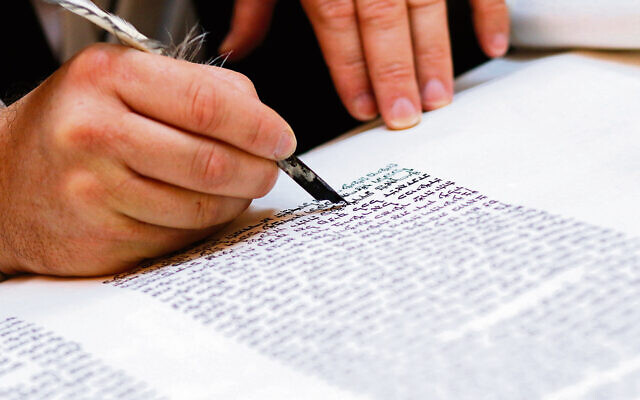

Given my decades of experience in reading the Torah during which time I have experienced most of what can go wrong I walked up to the bimah to see the problem. In a moment all was clear. A letter “vav” was split so the baal koreh had assumed that given an imperfection in its script the sefer was pasul – unfit for use. I immediately explained that while his concern was understandable in this case all was well and leining proceeded.

Before enlarging on this event and the reason for my view let us understand a few basic principles.

Firstly, to be useable, a Sefer Torah must be perfect. Certain words may or may not incorporate those letters “yud” and “vav” that serve as semi vowels, but in every sefer the particular instance of any such word will be identical. With one possible exception which I will leave for now, every word in every sefer is spelt the same way. A particular script generally embellished with “crowns” is mandatory (though inevitably there are stylistic differences – Ashkenaz, Sefard, Chassidic etc). However misspellings aside, broken letters, smudges etc make a Sefer Torah unfit till it is corrected (if possible). If it cannot be corrected (perhaps owing to serious water damage or simply decline with age) the sefer is either maintained in the Aron Kodesh and simply brought out for hakafot on Simchat Torah, or it is respectfully buried.

Yes there are letters that for particular reasons are smaller or larger than the balance of the text. For example the “ayin” of “Shema” and the “dalet” of “Echad” in the well known sentence “Shema Yisrael Hashem Elokenu Hashem Echad – Hear O Israel the Lord is our God, the Lord is One” are large. These two letters create the word “ed” (witness) as that sentence bears testimony to our basic belief.

Additionally the large “dalet” ensures we do not confuse it with a “resh” which would make the word “echad” read as “acher” meaning another, implying that the Lord is “another” – there are two Gods. There are many other examples, each with a purpose. The small aleph in “Vayikra – and He (God) called to Moshe” (Vayikra 1:1) was apparently intended by Moshe when he wrote the Torah as dictated by God, so that the word could be read “vayikar – and He happened upon Moshe.” This was a sign of humility as Moshe sought to minimise the suggestion that God deliberately called and spoke to him.

But how did it come about that over millennia of manuscript copying that could reasonably be expected to suffer from human error, the text with all its “peculiarities” is identical in every sefer of every community worldwide.

Because a key to the text is “mesorah” the tradition that takes us back to Sinai.

Think about it. Despite what you see in your chumash the Torah itself has no vowels (nikud) and no cantillation notes (trop). So how do we read it? All of these are an originally oral tradition. During the 10th century the Masoretes based in Tiberias developed the system of vowels and notes we use today to record those sounds that long preceded writing down of the notes. Given the danger that over centuries the wording/spelling of manuscript texts might have been corrupted they also created a reference text now referred to as Keter Aram Tzova (the Crown of Aram Tzova) that was referred to even by Rambam, which resided for centuries in the Great Synagogue of Aleppo and is now in Yerushalayim (albeit, sadly, now incomplete).

So now after all that introduction, what was the issue that Shabbat afternoon when the reading was in fact the first part of the reading for this Shabbat, parashat Pinchas?

The preceding parasha Balak read last week ends with the story of public indulgence in flagrant immorality led by Zimri, a prince of the tribe of Shimeon and Cozbi, a princess of Midian. A plague broke out and led to 24,000 deaths, stopping only when Pinchas took the initiative and executed those key violators of Israelite modesty.

This parasha then begins with Pinchas being rewarded for that action by God with “briti shalom – my covenant of peace”. And it is here that we find this unique spelling issue. “Shalom”, the word we all know as denoting peace is spelt “shin” “lamed” “vav” “final mem”. Yet in this case the vav is broken – and in fact must be broken – against all the principles of writing a Sefer Torah. Why? One explanation I once heard is to teach that even if necessity dictates, true, complete, unbroken peace cannot emerge from violence however much it may be considered necessary in certain circumstances. Indeed there is an eternal lesson in this little broken vav.

And, I might add such is just one tiny example of why we cannot truly understand Torah by just reading a translation, however good. A translation would never give you the information implicit in the unique way that a word is spelt. That “vav”, like all of Torah, may point in many directions. Every word, every letter and even every cantillation sound is filled with depths of meaning that cannot possibly be fully incorporated in any such translation.

Shabbat shalom,

Yossi

Yossi Aron OAM is The AJN’s religious affairs editor.

comments