Another horrendous chapter of the Jewish story

STEP into the Steri Palace and you are immediately plunged into the abyss of one of history’s most blood-soaked episodes – one which saw Jews persecuted, tortured and publicly burnt at the stake.

A massive bell, now weather-beaten and discoloured, was repeatedly rung to announce the timing of their execution and invite the hordes to witness the barbaric ritual, conducted with ultimate hypocrisy in the presence of men of the Catholic faith sanctimoniously clutching an open Bible.

Known also as the Palazzo Chiaramonte, the intimidating Steri Palace functioned as the headquarters of the Spanish Inquisition in Sicily’s capital of Palermo from 1601 to 1782. A chilling testament to yet another of the horrendous chapters of the Jewish story, it evinces unspeakable cruelty, unfathomable grief.

Enter its cells where Jews and the many others whom the Inquisition regarded as heretics were imprisoned and you cannot but go cold as a remarkably detailed etching of Jerusalem pleads with you to pause and reflect on the tormented souls who were there before you – a drawing likely scratched into the concrete wall with a Jewish prisoner’s handcuffs, using blood, urine and candle-wax for colouring.

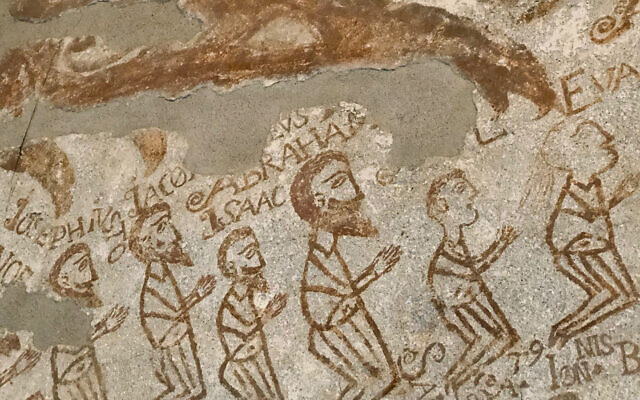

Another, equally compelling, diagram depicts Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Isaiah, Joseph and Aaron, while elsewhere, Hebrew lettering indicates the desperate thoughts of men about to be burnt to death in the nearby public square.

Believed to have had a presence in Sicily since the first century, the Jewish community eventually numbered an estimated 37,000, scattered throughout 50 towns and cities in communities ranging in size from 350 to 5000. Significant numbers settled on the island after the Romans overran Jerusalem, integrating into Sicilian society in such pursuits as farming, manual labour, medicine and philosophy.

Jews likely comprised as much as five to eight per cent of the island’s population until being either banished by the 1492 Edict of Expulsion decreed by Spain’s King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella or forced to convert to Catholicism.

A visit today tells a very different – and tragic – story. The story of a once-proud but destroyed Jewish community. Pore over maps of the Sicilian towns of Siracusa and Trapani and Cefalu and Palermo, and if you look hard enough you will find a street named Via Della Giudecca – the Street of the Jewish Quarter – or a variation thereof, indicating the former existence of what was once a vibrant and bustling Jewish Quarter. Take a walk to this Via Della Giudecca and you will quickly find yourself immersed in charming centuries-old cobbled alleyways, frequently narrow enough for visitors to simultaneously touch both sides with outstretched arms, the street signs in Italian, Hebrew and Arabic, and B&Bs still retaining “Giudecca” in their signage.

The walls speak to you simultaneously of tradition and history and persecution and destruction – yet another profoundly dark chapter in the Jewish story.

Keep walking and you discover a sign tellingly indicating the presence of a “Bagno Ebraico” – “Jewish Bath”; located beneath the Residence Hotel Alla Giudecca and accessible by descending scores of slippery steps, the mikveh is remarkably intact and functioning, with natural water still draining into and out of it hundreds of years later.

Poring over these maps, one cannot avoid being struck by the proliferation of crosses, indicating the ubiquitous location of cathedrals and churches across the island. What the maps do not tell you is that until the Jewish community was destroyed by the Inquisition, some of those self-same churches were once synagogues; indeed, at least one of them still houses a subterranean mikveh – today a well-advertised tourist attraction.

On January 12, 2017 the Archbishop of Sicily formally transferred to Palermo’s tiny Jewish community, believed to number a mere 70 people, a facility owned by the Church of St Nicolo Tolentino – but built on the ruins of what was once the Great Synagogue of Palermo – to function as the island’s first synagogue since the Inquisition. The chosen date was significant, January 12, 1493 being the deadline for the expulsion of Jews from the island 500 years earlier. How successful it proves to be in breathing a semblance of life into what was Sicilian Jewry remains to be seen.

Footnote: Our final stop before departing Italy was a centuries-old area of Rome – where, inadvertently, we came across half-a-dozen Stolpersteine, the so-called stumbling blocks which have been inserted into pavements outside apartment blocks across Europe to indicate the identities of Jews who were deported and murdered during the Holocaust and the locations from where they were seized. A terrible continuum from the story of the Inquisition.

Vic Alhadeff is CEO of the NSW Jewish Board of Deputies.

comments