Behind new film ‘Operation Mincemeat,’ the true story of WWII’s greatest deception

The movie tells how Britain used the body of a dead vagrant to trick Hitler into dropping Nazi defenses in Sicily, enabling its capture and turning the tide of the war.

LONDON — It was the greatest act of wartime deception. In the early hours of April 30, 1943, the British submarine HMS Seraph surfaced from the darkness, slipped towards the southwest coast of Spain, and dropped the body of a homeless vagrant who had died of rat poisoning gently into the sea close to the fishing village of Punta Umbria.

Dressed as a British airman and furnished with an elaborate cover identity, the corpse contained copies of top-secret papers purportedly outlining the Allied plans for the invasion of southern Europe.

The fake documents — designed to convince the Nazis the attack would take place on Sardinia and Greece — eventually reached the desk of Adolf Hitler. Convinced by German intelligence that they were genuine, he fatally ordered his forces to reinforce the supposed targets, thus shifting attention from Sicily, where the Allies successfully landed just under two months later.

The subject of a new film of the same name starring Colin Firth, Matthew Macfadyen and Penelope Wilton, Operation Mincemeat was masterminded and driven by Ewen Montagu, a British intelligence officer and scion of a prominent Jewish family. Montagu, who is played by Firth, later relished his role in deceiving Hitler.

“Joy of joys to anyone, and particularly a Jew, the satisfaction of knowing that they had directly and specifically fooled that monster,” Montagu said.

Although its impact is impossible to calculate precisely, the deception is seen by many historians as having played a critical role in securing the Nazis’ defeat. “The framers of Operation Mincemeat dreamed up the most unlikely concatenation of events, rendered them believable, and sent them off to war, changing reality through lateral thinking,” writes journalist Ben Macintrye in his account of the hoax upon which the film is based. “Operation Mincemeat was pure make-believe; and it made Hitler believe something that changed the course of history.”

Despite now receiving the Hollywood treatment, the cast of characters involved and the operation’s multiple heart-stopping twists and turns would hardly have seemed credible if they had been shoe-horned into a work of fiction.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the elaborate ruse behind Operation Mincemeat is believed to have originated from the pen of Ian Fleming, later the creator of the fictional British MI6 agent James Bond. In a September 1939 memo shortly after the outbreak of war, he laid out 51 suggestions for “introducing ideas into the heads of the Germans.” The 28th — “not a very nice one,” admitted Fleming and his boss, the director of naval intelligence, Admiral John Godfrey — was that “a corpse dressed as an airman, with dispatches in his pockets, could be dropped on the coast, supposedly from a parachute that had failed.” The memo confidently — and, it later became evident, falsely –asserted that there was “no difficulty in obtaining corpses at the Naval Hospital.”

The “not very nice” ploy was left to marinate for three more years before it was revived by Charles Cholmondeley, an eccentric 25-year-old RAF officer seconded to the security service MI5. It would eventually become a key element in Operation Barclay, which was designed to convince the Germans — against their best instincts and all military logic — that the strategically important island of Sicily would not be the next and first step in the Allied effort to recapture mainland Europe. As British prime minister Winston Churchill himself put it: “Everyone but a bloody fool would know it was Sicily.”

The genius of Operation Mincemeat was that it would be double deception. It aimed to persuade the Germans that Greece would be the focus of the invasion. At the same time, it would also attempt to fool them into thinking that the build-up of forces that appeared to be targeting Sicily was, in fact, simply part of an elaborate decoy.

Nonetheless, Operation Mincemeat was loaded with peril and fiendishly complicated. Indeed, if fake documents failed to find their way into the hands of the Germans once they washed up in Spain or if the hoax were rumbled, the consequences, Montagu warned, could be “far-reaching” and of “great magnitude.” As Macintyre writes: “If [Mincemeat] failed, then all the other elements of the deception might be revealed as part of an enormous fraud, allowing the Germans to reinforce Sicily.”

But, as Macintyre also notes, as a means to convey the deception, a corpse had an indisputable appeal: “Human agents or double agents can be tortured or turned, forced to reveal the falsity of the information they carry. A dead body would never talk.”

That did not mean, of course, that the dead body — and the documents it carried — could be in any way unconvincing. And this, perhaps, was Montagu’s greatest contribution.

The second son of Lord Swaythling, a wealthy financier and political activist, and his wife, Gladys, a member of both the Goldsmid and Rothschild banking families, Montagu became an attorney after serving in World War I. When war returned in 1939, he was too old for active services. He nonetheless joined the naval reserve.

With Godfrey’s approval, the fiercely bright and quick-witted Montagu was quickly promoted through the ranks of naval intelligence. He was soon appointed to run the “special intelligence” Section 17M, which Godfrey termed “a brilliant band of dedicated war winners,” and later took charge of all double agents involved in naval deception. Together with Cholmondeley, Montagu was then set to work on Operation Mincemeat. The pair, writes Macintyre, would “develop into the most remarkable double act in the history of deception.”

‘You can’t get dead bodies just for the asking’

Despite Fleming’s earlier assurances, purloining a corpse for a secret operation in wartime London was not a simple affair.

When Montagu first approached Bentley Purchase — an old friend and the coroner for the northern district of London — seeking to obtain a body for “a warlike operation,” he was given short shrift.

“You can’t get dead bodies just for the asking you know,” Purchase replied. “I should think bodies are the only commodities not in short supply at the moment [but] even with bodies all over the place, each one has to be accounted for.”

Reassured, however, that Churchill himself had approved the “warlike operation,” Purchase proved rather more accommodating. Having promised to look out for a suitable candidate, he informed Montagu of the arrival at the morgue of Glyndwr Michael, a 34-year-old homeless man with no family, who had died on January 28, 1943, after ingesting rat poison. The poison, Purchase predicted, would leave few traces as to the cause of death. It would thus be unlikely to contradict the presumption that, when it washed up on a Spanish shore, the body was the unfortunate victim of an air accident.

Montagu recognised, however, that the hard work was just beginning and the dead body now had to be given a convincing persona. “The more real he appeared, the more convincing the whole affair would be,” he later recalled. “Every little detail would be studied by the Germans.”

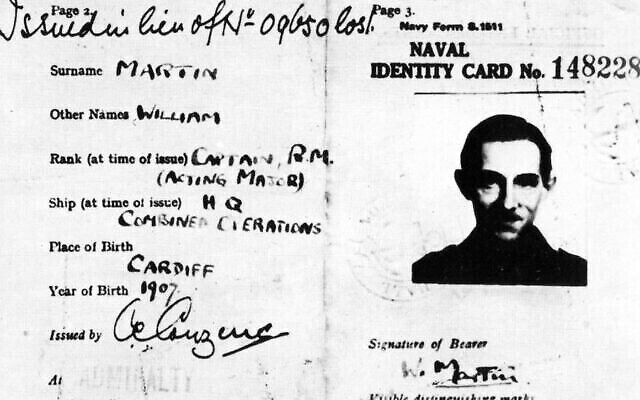

The credibility of the secret documents he was carrying thus rested on the credibility of the transformation of Glyndwr Michael into Captain William “Bill” Martin. “We talked about him until it did feel as if he was an old friend,” Montagu said of the hours spent with Cholmondeley constructing Martin’s personality. “He became completely real to us.”

Martin was furnished with much more than a uniform and military ID card. Through letters and “wallet litter,” a picture was painted of a public school-educated “thoroughly good chap”: a member of Pall Mall’s Army and Navy Club, who purchased his shirts from Gieves, smoked Player’s Navy Cut cigarettes, and frequented the Cabaret Club. A letter from his irritated bank manager concerning his overdraft — about which his father also fretted in another letter — hinted that Martin liked to live beyond his means. Pam, Martin’s supposed fiancé, was revealed in a photograph (in reality of Jean Leslie, a member of the naval intelligence unit), some rather cloying correspondence, and a bill for an engagement ring.

But, as Macintyre argues, the story of Bill Martin was, in some regards, perhaps “too perfect,” and presented a risk if the Germans began to look too closely.

“In Martin’s pockets there was nothing stray or inexplicable, nothing unlikely or meaningless,” he writes. “Everything tied together, everything added up… In the warped intelligence mentality, something that looks perfect is probably a fake.”

Equal care and attention were given to the official correspondence that was to be planted in the briefcase and attached to Martin’s body using a leather-covered chain. The most important document was a personal letter from Lt.-Gen. Sir Archibald Nye, vice-chair of the Imperial General Staff, to Sir Harold Alexander, a senior general based in North Africa.

Attempting to frame the deception, Montagu suggested, was “a crooked lawyer’s dream of heaven.” He determined that the falsified target should be “casually but definitively identified” and that the tone of the letter should have “personal remarks and evidence of a personal discussion” to indicate why it hadn’t been set by an encoded signal or diplomatic courier.

A painstaking, heated process of drafting and revision ensued until it was decided that Nye himself should be asked to draft the letter to make it as natural and convincing as possible. A single eyelash was planted in the completed correspondence in the hope that if it eventually found its way back to Britain, the intelligence services would be able to see if it had been tampered with by the Spanish or Germans.

The trap is set

Officially neutral but with a German spy network that was given almost free rein by Franco’s fascist regime, Spain was the natural location for attempting to get the fake plans into the Nazis’ hands. Moreover, Huelva was identified as suitable not simply because the tides and currents were most likely to wash the body up in the correct place, but due to the particularly pro-German bent of the fishing port. Adolf Clauss — “a very active German agent… who had excellent contacts with certain Spaniards, both officials and others,” according to Montagu — was, moreover, seen as just the kind of Abwehr agent who would quickly pick up any rumor of a dead British airman carrying documents and ruthlessly follow the scent.

On April 15, 1943, Churchill, laying in bed and smoking a cigar in his quarters at the Cabinet War Rooms underground complex, gave the plan the green light, subject to the approval of the Allied commander, Dwight Eisenhower. The prime minister was characteristically enthusiastic about the planned deception and sanguine when warned of the risk that the Spanish authorities might simply recover the body and documents and hand them straight back to the British. “In that case, we will have to get the body back and give it another swim,” Churchill responded.

Two days later, having been forced to defrost Michael’s frozen feet with an electric fire to get the boots on, Montagu and Cholmondeley accompanied the corpse as it was driven from London to a naval base in western Scotland. The body had been placed in a special tubular canister designed to preserve it during its submarine journey. As it was hauled aboard the Seraph, the submarine’s captain, Lt. Bill Jewell, told his crew it contained a top-secret meteorological device.

The action now turned to Spain where the operation faced perhaps its most delicate stage. Once the body was safely in the hands of the authorities, British intelligence engaged in a fine balancing act: London, the UK embassy in Madrid and the vice-counsel in Huelva, Francis Haselden, swapped increasing fraught messages by phone and cables which they knew the Nazis could intercept in order to stoke interest in the lost documents. Haselden had to appear keen to recover the briefcase but his efforts should not be so great as to lead the Spanish to hand them straight back to him before the Germans had had a chance to peek at them. The fact that the Spanish navy — the branch of Franco’s armed forces most sympathetic to the British — had taken possession of the documents added a further complication.

Haselden, a retired engineer and businessman with no espionage experience, performed the role adeptly. He persuaded the Spanish to cut short a planned autopsy due to the stench from the decomposing body and adroitly side-stepped an offer from the naval judge overseeing the process to hand the briefcase straight over to him.

With their antennae piqued, for over a week the Germans made multiple attempts to get their hands on the documents. After the canny Clauss repeatedly tried and failed to persuade the Spanish to let him view them, the Gestapo and the Abwehr in Madrid stepped in. Eventually, thanks to the assistance of Col. Jose Lopez Barron Cerruti, the head of Spain’s secret police, the Nazis were given an hour to view the contents of the elusive briefcase — just as the British had been hoping for. The documents were then returned to the Spanish who, in turn, attempted to cover their tracks before passing them to the British Embassy. Once they reached London by diplomatic bag, the eyelash was found to be missing, suggesting the fake letters had indeed been opened. Further scientific tests confirmed this initial finding.

Unexpected assistance

Of course, none of this proved that the Germans had bought into the deception. However, the British were now given some unexpected assistance. The documents were rushed to Berlin by Karl-Erich Kühlenthal, a senior intelligence officer in Spain and favourite of the Abwehr head, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. Kühlenthal was, however, a “one-man espionage disaster area,” according to Macintryre, whose mix of “eagerness and gullibility” had left a trail of missteps in its wake.

Kühlenthal, who didn’t appear to even consider the possibility the documents might not be kosher, had a pathological desire to please his bosses with a stream of intelligence revelations. This was born of a paranoia and insecurity which stemmed, in part, from the fact that — as some of his jealous colleagues were well aware — he had a Jewish grandmother but had been protected by Canaris, who had had paperwork issued which effectively “Aryanised” him. Kühlenthal was, Macintyre writes, the “ideal courier” for the forged letters.

In the Reich capital, the Abwehr delivered an initial, slightly hedged verdict. “The genuineness of the report is held as possible,” it declared as the documents were passed to the ultimate authority: the FHW, the intelligence branch of the German army high command. Its assessments were passed straight to Hitler, who had great faith in, and had handpicked, its head, Lt.-Col. Alexis Baron von Roenne. Von Roenne proceeded to deem the letters “absolutely convincing,” issuing not a word of caution about their reliability.

What Hitler was unaware of at this point, however, was that von Roenne, who had been appalled by atrocities he had witnessed in Poland, was a fervent anti-Nazi and was purposefully passing on information he knew to be false. Hitler, who had initially asked whether it was possible the corpse might have been “deliberately planted on our hands,” cast any doubts he may have harboured aside once von Roenne’s assessment was delivered to him. The Allies were, moreover, pushing at an open door in Hitler’s mind: he had long believed that an attack would come through Greece and the Balkans and that Sardinia would also be targeted.

Mussolini, who clung to the notion that Sicily was the most likely place for an Allied landing, was pushed aside. Greece, Sardinia and Corsica must be defended “at all costs,” Hitler ordered. Among the Nazi high command, any doubters — such as Josef Goebbels, who quietly confided his skepticism about the documents to his diary — kept their thoughts to themselves. The German military machine began to reorient its focus in just the manner the British had hoped: an 18,000-strong Panzer division was transferred from France to Thessaloniki; German troops and aircraft flowed into Sardinia, Greece and the Balkans; and torpedo boats were switched from Sicily to the Greek islands. By contrast, little effort was made to reinforce Sicily’s defenses.

Thanks to its code-breakers at Bletchley Park, British intelligence picked up the first signs that the Germans had fallen for the deception on May 14, 1943. “Mincemeat swallowed, rod, line and sinker by the right people and from the best information they look like acting on it,” a delighted Churchill was informed. For Montagu, the ensuing days as intelligence picked up further proof of the Operation’s success were “wonderful.”

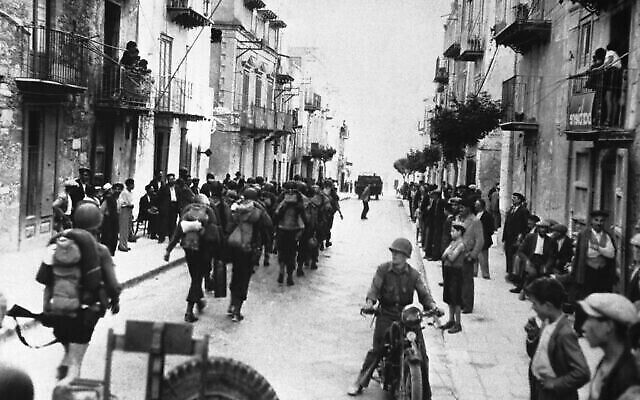

On July 9, 1943, the Allied invasion of Sicily was launched. But, even as it commenced, the Germans appeared to remain convinced that this was perhaps a ploy. Four hours after the attack began, 21 German aircraft departed the island in order to reinforce Sardinia.

As Macintyre details, British casualties were a fraction of those that had been predicted, as were the loss of naval ships. The campaign to capture Sicily, which was expected to last three months, was completed in 38 days. Moreover, Hitler, fearing that an invasion of the Balkans was still to come, rushed troops from the Eastern Front, where the Battle of Kursk was raging, to shore up his forces in the Mediterranean. The move allowed the Red Army to gain the initiative and the Soviets never looked back.

The role of Operation Mincemeat cannot be isolated from the other factors — not least Hitler’s existing fixation on the Balkans and his distrust of the Italians — which contributed to the Allied victory in Sicily; a vital staging post in the campaign to defeat Nazism. But the deception undoubtedly both played its part and helped save the lives of thousands of British and American troops.

For this, Macintyre says, Montagu deserves huge credit. “Without his combination of ‘extreme caution and extreme daring,’” he writes, “Operation Mincemeat could never have happened.”

comments