Books shed light on bravery in battle

This past year or so has seen the publication in Australia of three books covering a range of military subject matter of particular interest to the Jewish Australian reader.

A message from Dr Keith Sullivan

President of the Federal Association of Jewish Ex-Servicemen and Women (FAJEX)

When talking about The Great War of 1914-1918, it was often referred to as “the War to end all Wars” but it was never going to be. World War II and so many other devastating wars since then, have been, and are being, fought. And now the invasion of Ukraine.

Inevitably, whenever there are Jewish citizens, they are caught up in their nation’s conflicts one way or another, and certainly so in military service, whether as volunteers or conscripts.

This past year or so has seen the publication in Australia of three books covering a range of military subject matter of particular interest to the Jewish Australian reader.

Patterson of Israel by Henry Lew, Humanity in Medicine: The Life of Dr Stanley Goulston by Kerry Breen, and Ratbag Soldier Saint: The Real Story of Sergeant Issy Smith VC by Lian Knight, are based on widely separated geography, different eras and distinct experiences.

But in all three, there is a strong military flavour, with both an active service and an ex-service component, and a special Jewish Australian connection.

All three books tell of genuine heroism, of commitment and belief, and they exemplify the eternal values of decent society that always needs to be safeguarded, fought for, and which can never be taken for granted.

Lest we forget.

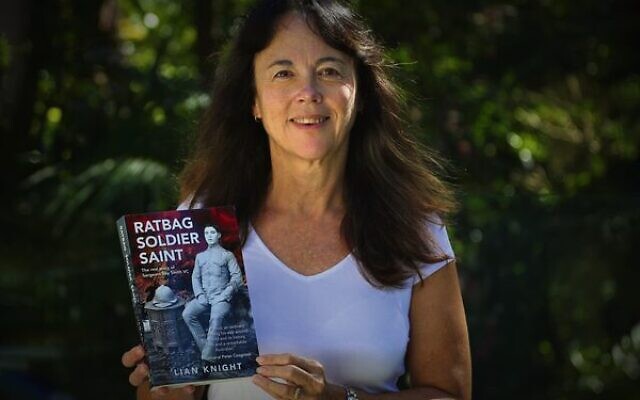

A granddaughter’s tribute to a VC hero

In Melbourne on September 10, 1940 – just a week before he would have turned 50 – World War I hero Issy Smith tragically died from ongoing ill-health, associated with his exposure to chlorine gas in the Western Front battlefields 24 years earlier.

But what the first Jewish non-commissioned officer to be awarded the Victoria Cross – the Commonwealth’s highest award for valour – packed into his short, yet remarkable life, is astonishing.

So much so that Smith became the stuff of legend, and the focus of about 2000 newspaper articles around the world, mostly published just over a century ago.

Yet hardly any of those reports were consistent, even about basics such as his birthplace and age, where he lived and what he did.

After doing extensive research – assisted by her father Maurice in his final years – Issy’s granddaughter Lian Knight wrote a comprehensive and moving biography about him, called Ratbag Soldier Saint: The Real Story of Sergeant Issy Smith VC.

It was officially launched in Melbourne last week in the lead-up to Anzac Day, by Patron-in-Chief of the Victorian Association of Jewish Ex-Service Men and Women, Major General Jeffrey Rosenfeld, and Essendon RSL Sub-branch president Ange Kenos.

Knight said, “It was an incredible experience to be able to write the book, and the more I got into it, the more I discovered.

“It keeps the memory of Issy’s life, contributions and sacrifices alive. But more than that, it’s a valuable record for future generations as to what he, and many others, had to struggle through, not only during the Great War, but afterwards too, particularly with health issues.”

The book clears up some muddy waters surrounding Issy – who was actually born Ishroulch Shmeilowitz in Constantinople in 1890, where his parents had fled from a Russian-controlled part of Eastern Europe, where Jews were being persecuted.

We learn of Issy’s daring and adventurous spirit, that was to serve him well in battle, but get him into loads of trouble as a child. When just 11, he ran away from home, and hid in a ship bound for London, where an older brother was living in the impoverished East End.

Before he turned 14, Issy was remarkably accepted into the 1st Manchester Regiment of the British Army, serving in it, mainly in India, until 1912, when he met his future wife, Elsie.

They moved to Melbourne together, but as soon as war broke out, Issy rejoined his old regiment, and by March 1915, he was fighting in the trenches near Neuve Chapelle in France.

His heroic deeds the following month, in the Second Battle of Ypres, are described in breathtaking detail by Knight in chapters 11 and 12.

As the Anzacs were landing at Gallipoli on April 25, 1915, Issy’s battalion was in the middle of a three-day march towards Ypres, but they were not told of their destination.

“So they assumed they were going to be sent to Gallipoli,” Knight said.

At Ypres on the afternoon of April 26, during a delayed attack on German positions, Issy chose to run – despite facing constant enemy fire – to injured Second Lieutenant Arthur Robinson, carrying him to a first aid post.

He then, again amid heavy fire, simultaneously rescued Sergeant James Rooke and Lieutenant Walter Shipster, who both had gunshot wounds, by carrying them, in turns, 230 metres back to his battalion’s trench.

After just an hour’s rest while suffering exhaustion and the effects of gassing, Issy joined an after-dark search for missing men in rough terrain. He came across more wounded comrades, and brought each one back to safety. In his own account, Sergeant Rooke wrote “the fact Issy escaped being hit was a sheer miracle … no-one ever deserves a VC more thoroughly than he does”.

Issy was indeed awarded a VC for that “most conspicuous bravery” four months later, becoming an instant celebrity in Britain and Australia, and a hero within both nations’ Jewish communities.

“What is less known, compared to the Western Front,” Knights said, “was what happened in battles in Mesopotamia [now Iraq] in 1916 and 1917 ,where the worst surrender in British military history, at that point, occurred in the Siege of Kut.

“There, 23,000 Allied troops were lost trying to rescue 13,000 trapped soldiers – and then many more were killed in the capture of Baghdad.

“You would have thought they’d send a VC recipient somewhere safer, and how Issy wasn’t killed there, I don’t know.”

Issy occasionally encountered blatant antisemitism while still in England, but always fought it. He sued a taxi driver in London who wouldn’t give him a ride because he was Jewish. And when a Leeds café owner refused to serve him for the same reason, articles and letters were published in newspapers across the world, expressing disgust at his treatment.

In 1927, Issy and Elsie moved back permanently to Australia, with their first child, Olive. Plagued by long periods of ill-health, Issy worked at every opportunity, but struggled on a meagre military pension when he couldn’t.

Nonetheless, he continued to support charities and involve himself in communal work, whether it be as a founding member of the Jewish Returned Soldiers’ Circle, or the Judean League of Victoria Auxiliary.

Even within two months of his death, he travelled to country Victoria to speak at World War II recruitment rallies, and volunteer at the Auxiliary’s fundraising events.

Rosenfeld said, “Issy Smith was tough and courageous, and a risk-taker as a soldier … putting the lives of mates ahead of his own.

“As with other VC winners, he had an uncanny ability to cheat death [in combat].

“Despite Issy’s own challenges in life, he advocated for veterans and personally helped many.”

Due to a procedural matter when Issy signed up in Melbourne for military service in 1914, he was considered an Imperial Reservist, so never got the opportunity to wear the Australian uniform.

But Knight said she is sure if Issy “had been able to, he would have proudly done so – he called Australia home”.

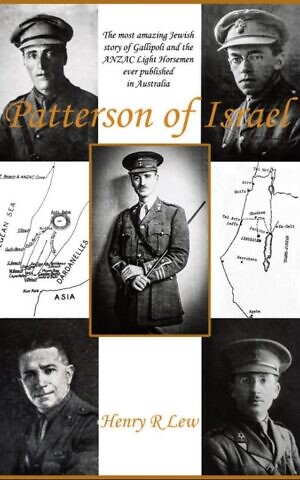

Diving deep into Patterson’s Jewish legion

When we think about Gallipoli as Australians, we automatically think about the courage under fire shown by the Anzacs.

As Jewish Australians, we should also think about the Zion Mule Corps – a 500-strong Jewish force formed as a part of the British Army, as envisioned by Vladimir Jabotinsky, which effectively became the first Jewish army unit in 2000 years.

It was commanded by an Irish Protestant, Lieutenant Colonel John Henry Patterson, who had never met a Jew before, but ended up becoming one of the most ardent Zionists.

It was commanded by an Irish Protestant, Lieutenant Colonel John Henry Patterson, who had never met a Jew before, but ended up becoming one of the most ardent Zionists.

In his book Patterson of Israel, Henry R Lew writes “without Patterson and his equally brave Zionist Mule Train, the Gallipoli campaign could not have survived eight weeks, let alone eight months”.

Lew goes into great detail – often utilising Patterson’s own reflections – regarding the Zion Mule Corps formation, its dramatic landing at W Beach in Gallipoli, and its vital role in distributing supplies across the peninsula, often under heavy fire.

Patterson described the battalion’s captain, Joseph Trumpeldor, as so gallant, that the heavier the gunfire he faced, “the more he seemed to like it”.

The book explores in detail Patterson’s appointment as leader of the Judean Battalion – a Jewish legion formed on August 23, 1917 to take part in combat in the Palestine campaign against the Turks.

In one vital battle centring on Umm esh Shert over the Jordan, Patterson’s battalion was stationed in the unforgiving heat for seven weeks.

In Patterson’s words, it was imperative “to convince them [the enemy] that we were much stronger than we actually were … this policy succeeded admirably – we harassed them so continuously that deserters started to come over to us”.

Patterson was also a vehement opponent of antisemitism, which he witnessed constantly being meted out to his men. He often risked his own position to protect them from that scourge.

The book also refers several times to Jewish Australian Eliezer Margolin, who after the war, on January 20, 1920, replaced Patterson as commander of the Judaean Battalion for several years.

Margolin received a Distinguished Service Order when in an Australian battalion at Gallipoli, and in the Palestine campaign, he accepted command of the 39th Royal Fusiliers Battalion, another Jewish battalion.

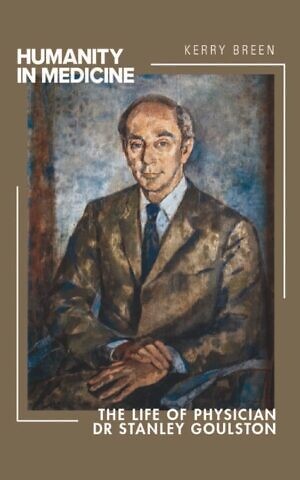

A doctor who thrived in danger

In April 1940, soon after graduating in medicine and enlisting in the Australian Army, Sydney’s Dr Stanley Goulston was appointed as the sole doctor for the 1500-strong 1st Pioneers Battalion – a joint engineering and combat force – that ended up in Tobruk in Libya in January 1941.

As Kerry Breen wrote in his book Humanity in Medicine: The Life of Physician Dr Stanley Goulston, the then 24-year-old took immense pride in becoming one of the famous Rats of Tobruk, who held out against German and Italian troops in an eight-month siege.

As Kerry Breen wrote in his book Humanity in Medicine: The Life of Physician Dr Stanley Goulston, the then 24-year-old took immense pride in becoming one of the famous Rats of Tobruk, who held out against German and Italian troops in an eight-month siege.

Goulston established four Regimental Aid Posts (RAPs), and was awarded the Military Cross for his bravery when treating wounded men under constant fire at a post in the Pilastria Sector near Fig Tree Hill, along a major defensive line.

His award citation reads: Captain Goulston has set a splendid example of devotion to duty, and courage under fire. On one occasion [at Pilastria], the enemy heavily dive bombed our battery positions in the vicinity of which was the RAP. Despite the attack and the fact that wounded men in the RAP were affected by the proximity of the bombs, this officer remained cool and carried on with his work, and by example, held the men together until they could be evacuated.

The book also tells Dr Goulston’s post-war impact in medicine, including becoming one of Australia’s first gastroenterologists.

A database with a difference

The Australian Jewish Historical Society maintains a database of details of more than 6500 Jews who served in the Australian military between the Boer War and World War II. It also has links to each person’s record at the National Archives of Australia.

To visit the database, got to ajhs.com.au/ajmd

comments