A child survivor’s story

Through the kindness of strangers, toddler Francine Lazarus was able to survive World War II, and recounted her amazing story to Yael Brender.

Through the kindness of strangers, toddler Francine Lazarus was able to survive World War II, often separated from her family. She recounts her amazing story in her new book. Yael Brender reports.

“THE very first thing I remember is my parents going to beg people to hide me,” recalled Holocaust survivor Francine Lazarus (née Kamerman). It was 1942; I was four years old. I remember it so clearly – first they went to a bakery.”

The Kamerman family had already tried to escape from Belgium to France in 1940, but by the time they arrived in Dunkirk, it was closed to civilian transport. They then paid a people smuggler to take them to Spain via Switzerland, but the trip didn’t eventuate because Francine had contracted whooping cough and the smuggler refused to take them.

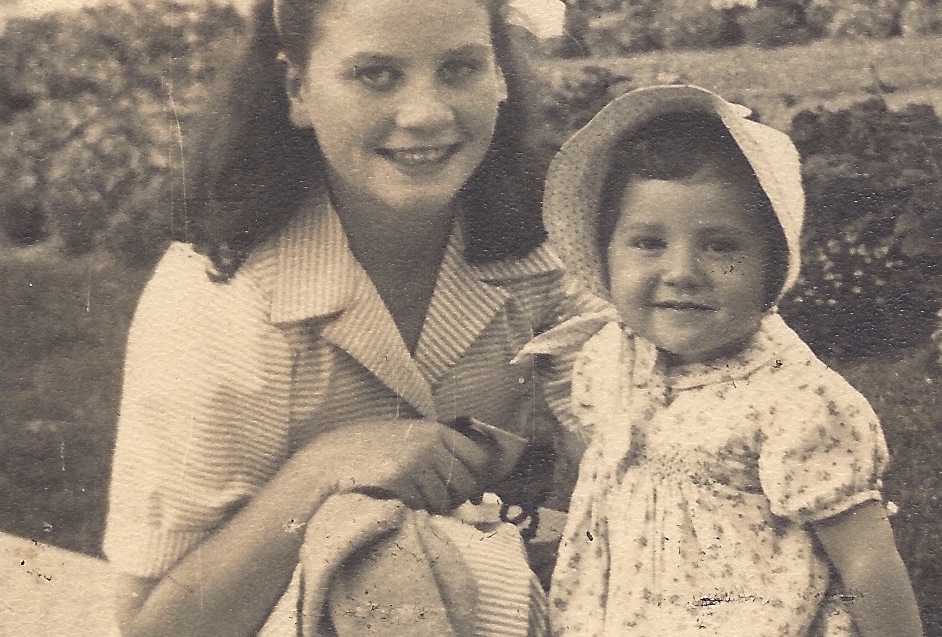

The bakery couldn’t help them, but the family’s landlord was a Belgian brothel-owner named Madame Jule who organised for four-year-old Francine to spend 18 months hiding on a farm with two married couples.

“I was left there completely by myself,” said Francine. “No parents, no brothers. Nothing.”

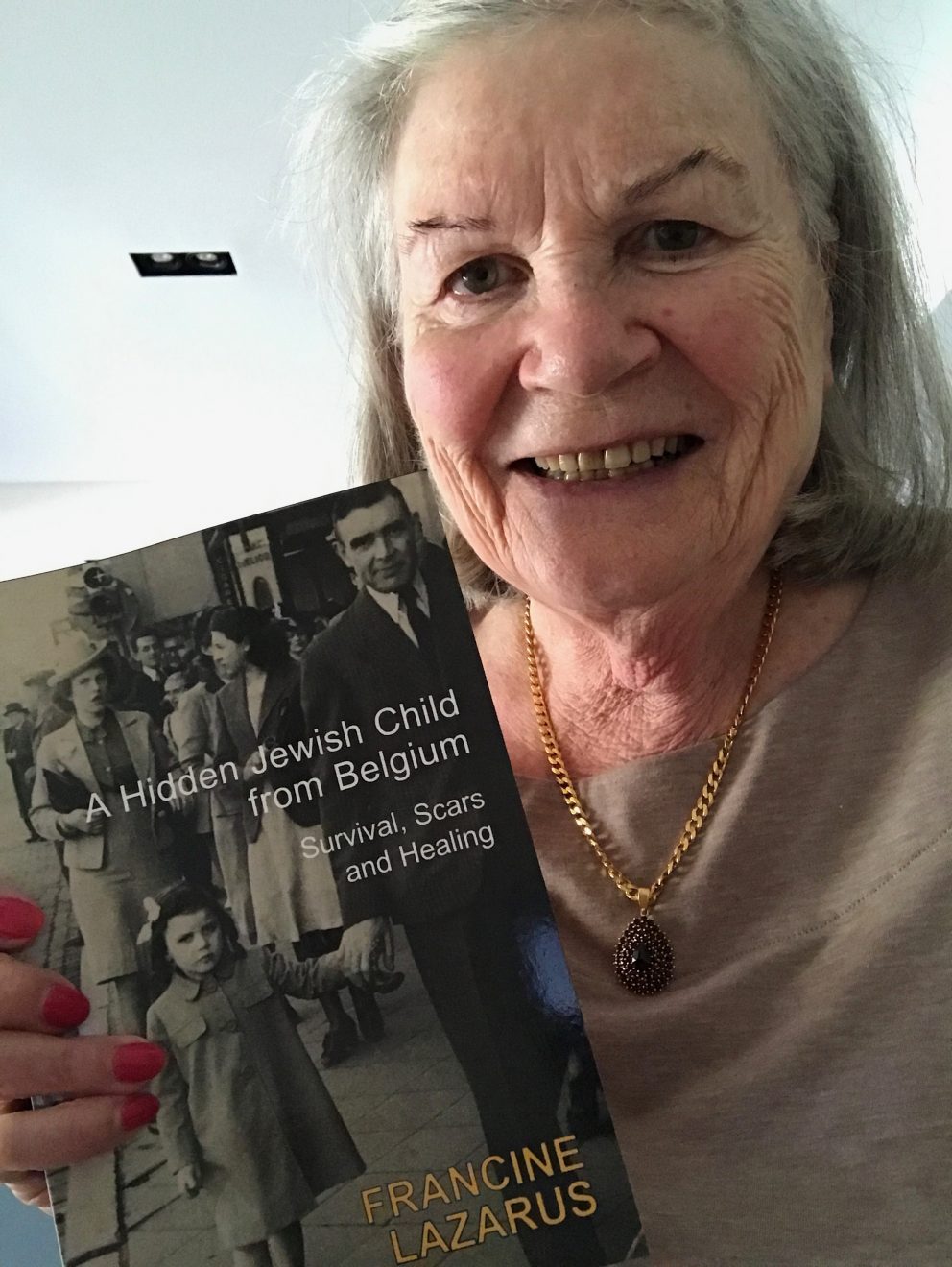

Francine has written about her life in her book, A Hidden Jewish Child from Belgium, which was launched recently at the Sydney Jewish Museum by former NSW governor Marie Bashir.

Her story of survival is both uplifting and heartbreaking. When the Belgian farmers were caught by the Gestapo, Francine was hiding in a haystack. She heard gunshots and never saw the men again. The women couldn’t run the farm on their own and Francine was sent back to the city.

“I walked along the streets with my father,” said Francine. “I remember him pushing me suddenly into a doorway and holding me inside his coat. I could hear boots marching, I could feel his heartbeat, I could smell his coat and then he was gone, and I was sent to a so-called safe-house.”

Aged five, Francine was shuffled from house to house every few days with a group of children. As they grew, their clothes and shoes became too small, so items were exchanged between children of different ages even though the fabric was riddled with lice. By the end of the war, she was hiding in her grandparents’ house with her brother Charly, waiting for liberation.

“The Allies landed on June 6, 1944, and although the Nazis had taken the radios, there was always a loose radio somewhere,” said Francine. “My dad would have known that the Allies were on the way and we were going to be liberated any minute.”

But in July 1944, Francine’s father got caught in a round-up and was sent to Malin, a town between Antwerp and Brussels, and then sent to Auschwitz on the last convoy out of Belgium.

“I think he must have been out on the street scrounging for food when they caught him,” she said. “There was absolutely no other reason to go outside.”

Francine’s father never knew if his family survived the war, and he wasn’t the only family member that Francine lost in the death camps. Hundreds of her paternal relatives were murdered, while her maternal family all died in the decimation of Biala Podlaska in Poland.

“Auschwitz has absolutely no record of my father arriving,” said Francine. “The Allies were at the door – they didn’t need records any more. That’s why I was always hoping that he was going to come back. It took a long time before we knew and an even longer time before we believed.”

Fewer than 1000 Belgian Jews were still alive by the time Allied forces liberated the camps.

With her mother unable to look after her, Francine was placed with a revolving door of foster families. She started school aged eight, and was accepted into the highest stream of high school education only four years later. But her mother forbade her to go, instead sending her to a typing school to learn shorthand.

“I was trying to prove to my mother that I was a good girl,” said Francine. “I hoped that one day she would say she loved me, but she never cared much for me.”

When Francine was 11, her mother remarried and had a daughter named Helen. At 13 Francine worked in a typing pool in winter and helped her mother and stepfather sell clothes in the summer. She hated the work, but did not dare disobey.

The cycle was broken when her grandmother, whose children had escaped to Australia before the war, booked tickets for Francine and herself by ship to Sydney, which arrived in the week of Francine’s 21st birthday.

“The sun was just starting to shine, and it was so beautiful. And I knew that I would love it. I knew that I had never seen anything so beautiful,” said Francine.

Her family met them at the dock, and she went to live with an aunt. For the first time in her life, she had a bedroom to herself. Thanks to her knowledge of French, she worked as secretary to the Belgian ambassador, at one stage serving as the acting chancellor at the Belgian embassy.

“For someone who’d had four years of schooling, it wasn’t bad,” recalled Francine. “I joined Alliance Francaise. Life was good.”

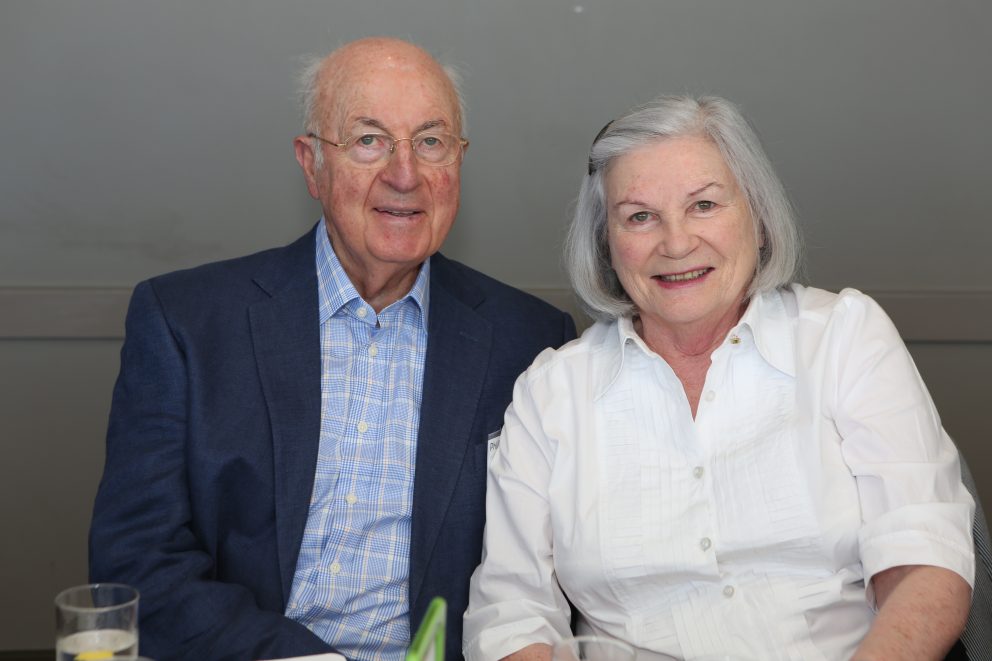

Francine met her husband Phillip at the Belgian embassy in 1962, was married in December 1963 and now has three children and three grandchildren. She took the HSC at TAFE when she was 40 and now has a Bachelor of Sociology and French and a Masters degree in French.

In 1977, Francine went back to Belgium for the first time, but she felt lost there. She couldn’t remember anyone she had met during the war and couldn’t find any of the houses where she had lived.

She has also visited Auschwitz twice, where she wandered the remains of the camp and spoke to her father in Yiddish.

“It was a hellish time,” said Francine. “People imagine the gas chambers like little rooms, but they are enormous. You can’t visualise it until you’ve seen the size of it. These people were pushed, standing room only, thousands of them. Machinery working, hour after hour after hour … I can only imagine.”

Before she wrote A Hidden Jewish Child from Belgium, Francine visited archives in Poland, Russia, Germany and the Ukraine. She found some records of her grandparents’ births and marriages, as well as her father’s transport manifesto, but it wasn’t easy.

“The Jews used to keep their records in the synagogue,” Francine explained. “But the Nazis came into many towns and villages and gathered the Jews, locked them in the synagogue, barred the doors and set them on fire. They burned the Jews, prayer books and records.”

She now dedicates her life to researching her family, visiting her husband in the Montefiore home and donating to a variety of Jewish charities, including WIZO, UIA and Magen David Adom.

“I can’t bear to think of a child in need, a child crying,” said Francine of her philanthopy. “A child that will never reach its potential unless it is helped. A child like me.”

YAEL BRENDER

A Hidden Jewish Child from Belgium by Francine Lazarus is published by Vallentine Mitchell. It is available from the Sydney Jewish Museum (www.sydneyjewishmuseum.com.au), $30.

comments