As a child, Tony Bernard didn’t really have any religious education. He would sit in the playground during scripture class. When he asked his father, Henry, what religion they followed, he was told nothing. That he could decide when he was 18.

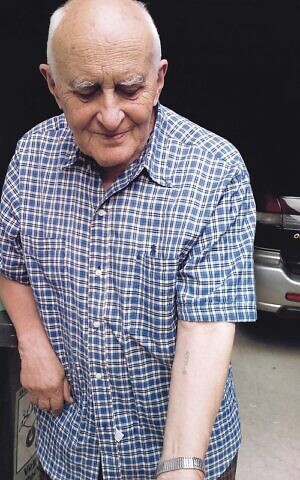

While Henry would talk to his children about the concentration camps – they could, after all, see his tattooed number – he never really talked about his family and what happened to them.

“He grew up in a secular Jewish family in Poland,” Tony explained, sharing his dad’s story with The AJN. “They did celebrate the main festivals, but they weren’t particularly religious. He occasionally went to synagogue, but after the Holocaust he just turned his back on religion. He was so scarred by antisemitism, particularly in Poland, and ongoing antisemitism after the war.”

According to Tony, Henry kept his religion a secret after the war, remaining in Poland for a few years to study medicine. It was a conversation that Henry overheard that was the final straw.

“They were talking about it [the Holocaust] at the university cafeteria, and some guy at his table made a comment, along the lines of ‘it’s such a shame he didn’t finish the job properly’,” Tony said.

“That’s why [Dad] came to Australia and that’s why he anglicised his name – he switched his middle name and surname around and gave us all English names.” He was trying to protect his loved ones from the antisemitism that he experienced.

As Tony grew up, Henry began to reveal the full extent of what happened during the Holocaust. Decades of research and conversations with his father have resulted in The Ghost Tattoo.

“When I was young, I’d ask him questions about his earlier life – what happened to his family, what happened to his girlfriend, what’s the scar on his elbow or even what happened to their town [Tomaszow]. He’d just say that he didn’t want to talk about it, so we respected that and just didn’t go there,” Tony recalled.

Henry was ashamed mainly due to his involvement with the Jewish police. It was only when Tony began talking to Professor Konrad Kwiet at the Sydney Jewish Museum that he realised what that all meant.

“I didn’t realise there was a stigma, I didn’t understand the negative side of it,” he said. “Professor Kwiet explained to me that in the past, my father would have been really criticised or condemned if he’d started talking.”

Tony believes that Henry was put into the Jewish police by his father, who, alongside other parents, were volunteering their sons to try and keep the organisation honest. But, despite this, Henry was still ashamed of his involvement, feeling like he had been inadvertently helping the Nazis.

“It was through writing this book that I really started to understand his position and his reserve in discussing the painful things but also the ambivalence he must have felt,” Tony said.

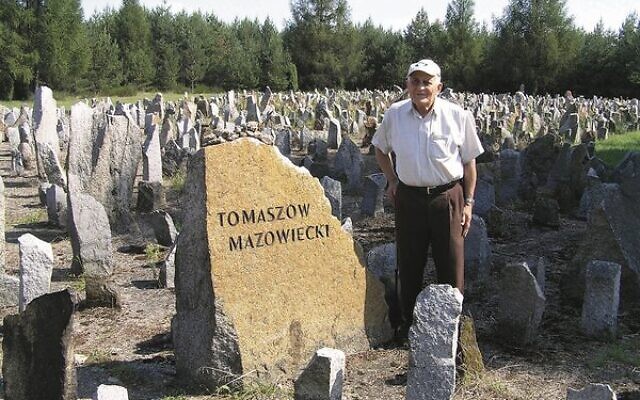

Tony travelled to Poland with Henry four times throughout his life, and with each visit, more and more was revealed.

A turning point came after Henry watched Schindler’s List. He moved from trying to conceal his past to wanting to share it with those around him.

Henry took part in director Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation interviews, and in 2006 he told Tony that he wanted to tell his story – no interruptions, no questions, just his own story.

“I printed it out as a rough draft, and he went through it and put in his corrections,” Tony recalled.

The biography was taken to the Sydney Jewish Museum and Professor Kwiet encouraged Tony to take it even further, explaining that as those involved with the Jewish police often did not put things on the record, the biography was an important piece of history. So, Tony began to gather evidence to support his father’s story.

He wanted to tell his story – no interruptions, no questions, just his own story.

In the War Crimes Trial Archive, Tony found his father’s entire audio testimony which he describes as “absolutely precise and clear”, explaining that Henry had an astonishing memory.

He described one trip to Poland during which his father took him around Tomaszow, describing things in such detail it was like he was almost reliving it, even down to the location of bullet holes, and describing a giant underground factory building jet aircraft, which was proven to be true.

Indeed, it was Henry’s evidence that convicted Gestapo executioner Georg Boettig, who refused to confess to any crimes. As Tony explained, the judges described Henry as “a unique witness in the trial that they believed above all others”.

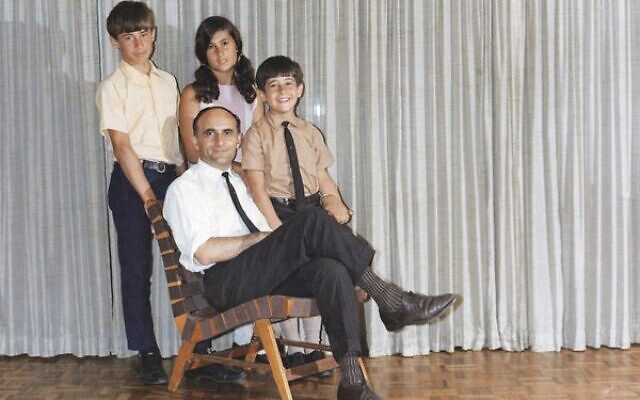

Despite all the horrors that Henry experienced, he gave his family a wonderful childhood growing up in the Northern Beaches of Sydney, which is something Tony is forever grateful for.

“He had all these near-death experiences. I’ve got great respect for him, his resilience, his toughness to survive all of that and have a reasonably normal life,” Tony said.

While at the end of the book, Tony says he continues to find and piece together bits of the puzzle, he hopes The Ghost Tattoo can stand as a record of what happened to the community of Tomaszow.

He also wants readers to understand that many of those who were forced into leadership positions in the ghettos and camps faced huge dilemmas, that caused ongoing angst and shame.

It was, after all, what Henry wanted when he eventually shared his story.

The Ghost Tattoo is published by Allen & Unwin, $32.99 (rrp)

comments