Seventy-five years ago this week, the United Nations General Assembly voted by 33 votes in favour, 13 against and with 10 abstentions, to partition the land between the Mediterranean Sea and Jordan River into two states, Jewish and Arab.

We know the history of what happened next; the State of Israel was subsequently declared in May 1948 and immediately forced to defend itself against five Arab armies, ultimately prevailing with increased territory. Today Israel is a thriving, high-tech, economic powerhouse.

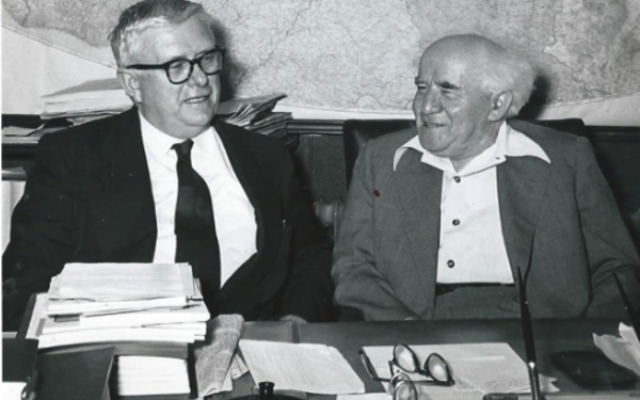

But history may have been very different if not for Australia’s Labor foreign minister at the time, Dr Herbert Vere ‘Doc’ Evatt, who was instrumental in seeing both the partition plan and recognition of the fledgling Jewish state through the UN.

In 1947, as chairman of the Ad Hoc Committee on Palestine, Evatt strongly favoured partition over the UN Special Committee on Palestine’s (UNSCOP’s) other stated alternative – preferred by the Arab nations – that a single state be formed in the land which had, since World War I, been administered by British mandate.

“Evatt wanted to become president of the United Nations,” Australia-Israel Labor Dialogue co-convenor Adam Slonim said.

“He didn’t get it till later. What he was given when he first had a go in 1947 was chairmanship of the Ad Hoc Committee on Palestine. That was considered a hot topic, and a consolation prize.”

And while he initially knew little about the Middle East, “because of his legal background he was an admirer of Louis Brandeis. And that became influential in his views on Zionism,” Slonim said.

Two subcommittees were formed, one to argue each case to the Ad Hoc Committee.

Evatt said at the time, “We really have to choose between recommending a scheme of partition on the one hand and a complete Arabian unitary state on the other; the latter state puts 600,000 Jews at the mercy of the Arabs.”

His advocacy saw the partition proposal – with Jerusalem to be administered as an international city – adopted after a vote of the Ad Hoc Committee.

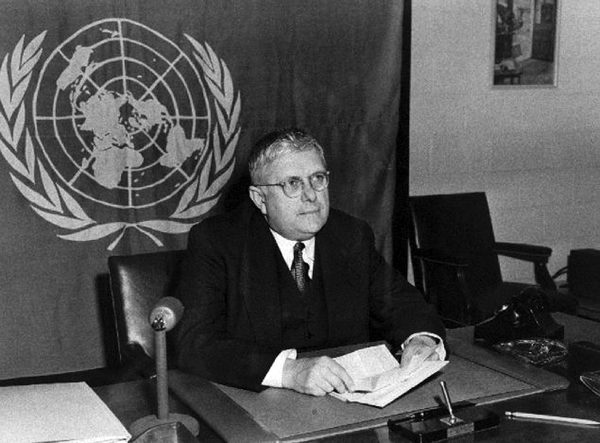

A two-thirds majority of the UN General Assembly – at a meeting chaired by Evatt – then ratified the plan.

A telegram to Evatt from the Jewish Agency for Palestine on December 2 stated, “We beg to convey to you our grateful appreciation of your wise and untiring guidance in the deliberations of the Ad Hoc Committee which prepared the ground for the United Nations’ historic decision for the re-establishment of the Jewish Commonwealth in Palestine.”

Evatt told a Zionist Federation of Australia and New Zealand dinner in Sydney a month later of the deliberations: “There was much lobbying and a certain amount of carping.

“Last-minute efforts were made to have the decision deferred, but this would have been as bad as a straight-out admission of defeat.

“This UN decision will certainly bring hope and relief to the Jewish people, who have suffered so greatly for so many centuries, and more particularly in latter years under the barbarity of Hitler.”

Under Evatt, Australia was also one of the first nations to fully recognise Israel.

“Australia’s decision to fully recognise Israel was as inevitable as it was just. The legal basis of Israel’s existence was unassailable and rested on a decision of the assembly, and it is the established policy of the Australian government and the Australian labour movement to give unwavering support to the decisions and principles of the United Nations,” he said.

“There was much lobbying and a certain amount of carping. Last-minute efforts were made to have the decision deferred, but this would have been as bad as a straight-out admission of defeat.”

As General Assembly president, in 1949 he advocated for Israel’s admission as a UN member state, later calling it the “most significant moment” of his presidency.

He was later given a medallion by the State of Israel as a mark of gratitude.

In 1960 he gave it to Sydney’s Moriah College as a gift, where it is on display alongside a plaque.

Former senior vice-president of the NSW Labor Party and Labor Israel Action Committee member Michael Easson said that without Evatt’s “decisive” influence, “it may have been a very different outcome”.

“I think there was a moment of time where massive sympathy for the creation of Israel was the very significant thing in Australia, [it] was bipartisan,” he said.

Within the “insular-thinking” labour movement, Easson said it was a rare moment of “thinking more broadly and internationally”, noting the tragedy of the Holocaust, which “was relevant to forming Evatt’s views about what he should do”.

Also relevant, Easson said, was Evatt’s association with New South Wales Labor MP Abe Landa, a member of the Jewish community who travelled with Evatt to New York and San Francisco as he sought support for the creation of a Jewish state and who observed some of his committee meetings at the UN.

“And it’s interesting that the labour movement itself, as well as Australia generally, have forgotten the role that we played in the formation of Israel,” Easson said.

“All of this history is forgotten, and needs to be recalled … by the labour movement in particular, because it’s among our proudest moments.

“That achievement of Evatt needs to be celebrated.”

Easson argued that many of Evatt’s achievements have been forgotten because of the subsequent history after Labor went into opposition in December 1949, overshadowing his achievements as foreign minister.

“Evatt is a tragic figure in Australian political life. He was destined for great things,” he said.

After the Chifley government’s defeat in 1949, Evatt became opposition leader, a post he held at the time of the famous 1955 split in the Labor party that divided allies, ended friendships and consigned the party to opposition until 1972.

“His whole career is overshadowed by the split and all that happened after that,” Easson said.

“Most people in the Labor Party wish they’d never heard of Evatt and see him as a disaster. But when he was foreign minister has was an amazing figure.”

He noted that in three of Australia’s most significant foreign policy achievements – Australia’s contribution to the Allies’ victory in World War II, the creation of Israel and the creation of Indonesia – Evatt was in the thick of things. “What other person can we say had that impact?”

Speaking of impact, the partition plan Evatt championed remains at the heart of Labor’s thinking today, according to Slonim, especially in light of the fact that the Arab half of the partition has never been realised.

“The origin of the Jewish people is in the hills of Judea and Samaria. We’ve got the archaeological record,” he said.

“We may have had continuous presence over the course of 1900 years, but at the end of the day, it became part of the Ottoman Empire and then a land that had generations of local inhabitants.

“The indigenous people started returning and it created conflict, and therefore was given to the League of Nations, and then, of course, the mandate was given to the United Nations to resolve, and the resolution occurred after the Shoah.

“And one of the enduring issues that actually represents today is in Labor, Israel was created as a function of white man’s burden from the guilt of the Shoah … but the price was the local Arab population.”

Slonim said Evatt “knew that the Jews were indigenous”.

But due to the “irreconcilability between the Jews and Arabs” at the time, he also knew partition was the only solution.

“Evatt was bright and smart in seeing that there needed to be this division. And it needed to be done properly, and it needed to be done within the legal mandate,” Slonim said, adding, “Everybody’s policy today is exactly the policy of 1947. Partition, separation.”

He said Evatt also recognised “the irreconcilability of the contest over Jerusalem”.

“So Jerusalem is decided to become an international city,” Slonim said, noting that the reverberations of that decision echoed right up to the federal government’s decision last month to reverse its predecessor’s recognition of west Jerusalem as Israel’s capital.

“It’s a reversion to the status quo … which is Jerusalem, east and west, and the Old City in particular, are to be negotiated,” he said.

“So Labor is actually holding the line. Unfortunately in Labor, there are elements which, of course, because of intersectionality, [believe] the oppression of Palestinians is the oppression of all people, and we know where that’s led.

“But Evatt’s vision is more relevant today than it’s ever been.”

comments