Dressed in matching purple hoodies and shirts, with gold fringes attached to the bottom in observance of Deuteronomy 22:12, hundreds of members of a controversial Hebrew Israelite group marched through the streets of Brooklyn last month.

“Hey Jacob, it’s time to wake up,” they chanted, using a term for people of colour who have yet to embrace their “true” identity as descendants of the biblical Jacob, later called Israel. “We got good news for you: YOU are the real Jews.”

The march and a demonstration that followed at the Barclays Centre were organised by Israel United in Christ (IUIC), in solidarity with Brooklyn Nets star Kyrie Irving, who was suspended for eight games after he posted a link to an antisemitic film on social media last month and then was slow to apologise. But IUIC has also used the controversy to promote its incendiary ideology and recruit new followers into what it calls “God’s army”.

After the demonstration the group’s founder posted a message on his Twitter account. “We are not here for violence,” Bishop Nathanyel Ben Israel wrote. “We are here for the spiritual war.”

Before 2019, those American Jews who were even aware of the once-obscure Black Hebrew Israelite spiritual movement likely associated it with the loud but nonviolent street preachers who would harangue pedestrians in city centres. In December of that year, however, extremists professing Israelite beliefs attacked a kosher grocery store in Jersey City, New Jersey and a Chanukah party in Monsey, New York. Two Jews were killed in Jersey City, and a 72-year-old rabbi who was stabbed in the head in Monsey died from his injuries three months later.

With the memory of those attacks still fresh, and against the backdrop of a surge in public expressions of antisemitism combined with threats of violence against Jewish communities emanating from other extremist corners, the militant posturing of IUIC has alarmed many Jews already on edge.

Rabbi Mordechai Lightstone of Crown Heights observed on Twitter that the Israelites who regularly preach near his home on Shabbat have been “particularly aggressive” of late, heaping verbal abuse on both him and his children.

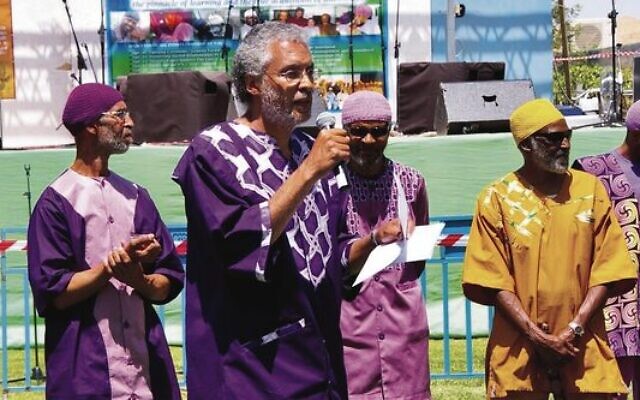

Photo: Corinna Kern/Flash90

The recent IUIC rallies give the impression that the radical wing of the Hebrew Israelite movement is large and riled up. Meanwhile, recent comments by rapper Ye (also known as Kanye West) and Irving that align with elements of Hebrew Israelite doctrine suggest the movement has broad support among powerful Black celebrities.

But how big is the movement in reality? What percentage are extremists who assail Jews as impostors who stole their heritage from them? And if Black Israelism has entered the marketplace of mainstream religions in the United States, should Jews be concerned?

The numbers

The only available statistics were collected as part of a small survey conducted by evangelical Christian research firm Lifeway in 2019. For that survey, which sought to capture African-American attitudes towards Israel, 1019 African Americans were asked, “Which of the following best describes your opinion of Black Hebrew Israelite teachings?”

Sixty-two per cent said they were not familiar with the teachings, but 19 per cent said they agreed with “most of the core ideas taught by Black Hebrew Israelites”, and four per cent considered themselves Hebrew Israelites. The 2020 US census put the Black population at 41.1 million, so extrapolating from the survey, there are approximately 1.6 million Hebrew Israelites and 7.8 million people who may not identify as such but who agree with its main teachings.

For lots of these people, the attention that West and Irving have brought to their belief system has been validating.

“The suspicions that a lot of folks have toward the Jewish community, they think they’re vindicated now,” Christian activist and author Vocab Malone told JTA.

Lifeway executive director Scott McConnell told JTA, “I know there are some pastors at African-American churches that have concerns about some of their parishioners being led astray by the teachings of the Hebrew Israelites.”

Malone, who uses an alias in keeping with hip-hop culture, is a close observer of the Israelite world. The Phoenix resident frequently engages in debates on the street and online with members of groups described as hateful by the Southern Poverty Law Centre in hopes of convincing them to follow what he considers to be the true path of Christianity.

Founded in 2003, IUIC has proven the most adept at creating public spectacles and garnering media coverage. The group operates 71 US chapters and 20 internationally, according to the Anti-Defamation League. Malone estimated that national membership has grown from around 5000 in 2015 to around 10,000 today. Other radical groups likely have much smaller memberships but don’t share any figures, preferring to “play their cards close to their chest”, Malone said.

These estimates suggest the extremists comprise a very small percentage of the 1.6 million Hebrew Israelites living in the United States.

Ultimately, IUIC has a goal of recruiting 144,000 Black, Latino and Native American people who will be spared by God during the end time, as foretold in the book of Revelation. In order to achieve this goal, the group sends representatives to proselytise overseas, including in parts of Africa and the Caribbean.

An online movement

The camps have greatly expanded their reach in recent years, taking their message from street corners to the entire globe thanks to the internet and social media. IUIC members run dozens of YouTube, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter accounts where they post a constant stream of videos and memes, many containing antisemitic tropes. One recent Instagram post shows a startled-looking Chassidic Jewish man holding his hat above the words “The Synagogue of Satan”. Louis Farrakhan, the leader of the Nation of Islam, uses similar language about Jews. A video he recorded last month defending West and Irving has been viewed millions of times.

The main IUIC YouTube channel has 126,000 subscribers and 29.4 million video views. A series of videos posted three years ago on the channels of local chapters provide some insight into how members hear about IUIC and why they join.

The most common way these members say they found their way to the camp was via videos they watched online. “Prior to actually coming to IUIC, I did do some Israelite window shopping,” recounts Officer Joshua of IUIC Tallahassee. “I always questioned myself, why is it that our people are at the bottom? How come we get the worst jobs and so forth? I knew Christianity wasn’t answering my questions, so what I did was I just started soul searching.”

Joshua says he stumbled upon a video of Bishop Nathanyel and other IUIC leaders preaching on the street. “I was like man, these brothers really know what they’re doing, they really have our history,” he says. “That’s what actually made me do more research on IUIC and the truth.”

In another video, Sister Ezriella from the Concord, North Carolina, branch explains that as a young adult, she felt uncertain about her life’s purpose. Then her mother shared information with her about IUIC. “She was so happy it changed her life, I had to take notice and I had to come check it out for myself,” she says. “I fell in love with it. I fell in love with finding out who I am.”

A number of Black, male celebrities have also been drawn into the wider Israelite orbit in recent years, including rappers Kendrick Lamar and Kodak Black, TV host Nick Cannon, boxer Floyd Mayweather and retired NBA player Amar’e Stoudemire.

Lamar, who famously rapped “I’m a Israelite, don’t call me Black no mo’” on a 2017 song, learned about Israelism from a cousin who was involved with IUIC. Black began identifying as a Levite in 2017 after studying scripture with an Israelite priest while serving a jail sentence in Florida. Stoudemire has said his mother taught him he had “Hebraic roots”. He officially converted to Judaism in 2020, a step most Israelites reject because it contradicts their claims of already being authentic Jews.

Isabelle Williams, an analyst at ADL’s Centre on Extremism, said celebrity endorsements can have a big impact because they come from figures who are widely respected.

“If people came upon an extremist Black Hebrew Israelite group street preaching, it might be easier to dismiss it and recognise the extreme ideology behind it,” she said. “But when it’s being shared by these influential figures, people might be less likely to recognise the really insidious ideology and dangerous antisemitic conspiracy theories that are behind these statements.”

“Israel and Judaism must figure out a way to better accommodate these communities. This is not going to fade away, and it shouldn’t. It will intensify as the awakening continues.” – Ahmadiel Ben Yehuda

Rabbi Capers Funnye is the most prominent Israelite leader in the US. He serves as chief rabbi of the International Israelite Board of Rabbis, an organisation that provides spiritual guidance to about 2500 people in the US, along with tens of thousands of Israelites in southern and west Africa.

In an interview, Funnye condemned West, Irving and the radical Israelite camps that have rallied around them. “God is never about divisiveness,” he said. “God is never about hatred.”

A member of the Chicago Board of Rabbis and the leader of a Chicago synagogue with a mixed membership of around 200 Jews and Israelites, Funnye was at pains to differentiate his community from IUIC and its ilk. His follows the Torah and supports the state of Israel, he said, while others follow both the Old and New Testaments, worship Jesus and reject Israel’s government as illegitimate.

“Whatever army that Kyrie is speaking about, we are not a part of his army,” he said, referring to a comment Irving made about how he has “a whole army” behind him.

But Funnye said another of Irving’s recent statements – “I cannot be antisemitic if I know where I come from” – resonated with him and his congregants.

“We are Semitic,” he said of Black people who identify as Israelites, “so now we really have to draw a line when antisemitism is only defined by one’s complexion or ethnicity. We were not the ones that racialised Judaism, and we will never racialise it because Jews are not a race.”

Outside the US, the largest organised group of Hebrew Israelites is located in Israel. The African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem are a Dimona-based community of more than 3000 African-American expatriates and their Israeli-born offspring.

African Hebrew Israelite youth serve in the Israel Defence Forces. After 53 years in Israel, the community has never been fully accepted, in part because they are not Jewish according to halachah, or Jewish law. Currently, some 100 community members are being threatened with deportation for living in the country illegally.

Ahmadiel Ben Yehuda, the African Hebrew Israelites’ minister of information, said he interpreted Irving’s remarks as a reference to “the global awakening of people of African ancestry to their Hebraic roots”. He said the backlash Irving has faced shows that the conversation around this awakening must involve qualified representatives of communities who can cite reputable sources – not documentaries such as the one Irving boosted, Hebrews to Negroes: Wake Up Black America – in support of their claims of Israelite ancestry.

“What is certain is that Israel and Judaism must figure out a way to better accommodate these communities,” Ben Yehuda said. “This is not going to fade away, and it shouldn’t. It will intensify as the awakening continues.”

How this awakening will affect Jews and established Jewish communities remains to be seen.

In September, George Washington University’s Program on Extremism released a report titled Contemporary Violent Extremism and the Black Hebrew Israelite Movement. The report noted that the “predominant threat” today comes not from Israelite groups themselves but from “individuals loosely affiliated with or inspired by the movement”.

Malone, the Christian activist, cautioned that as the extremist wing of the Israelite movement grows, more violent lone wolves may emerge.

“There’s a big funnel with any movement, and the bigger the funnel is, you get certain things down at the bottom,” he said. “This is not Buddhism. This is a different kind of thing with a different kind of rhetoric.”

IUIC did not respond to requests for comment.

JTA

comments