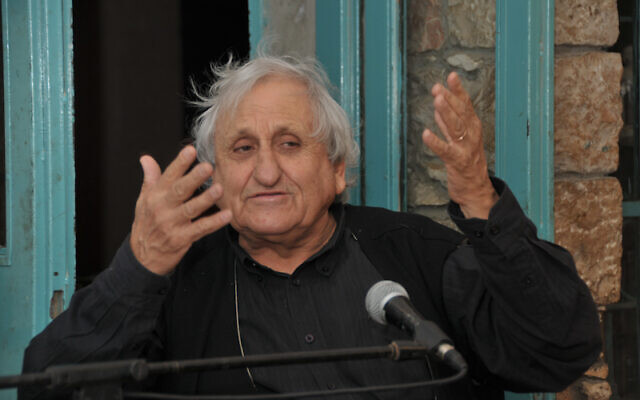

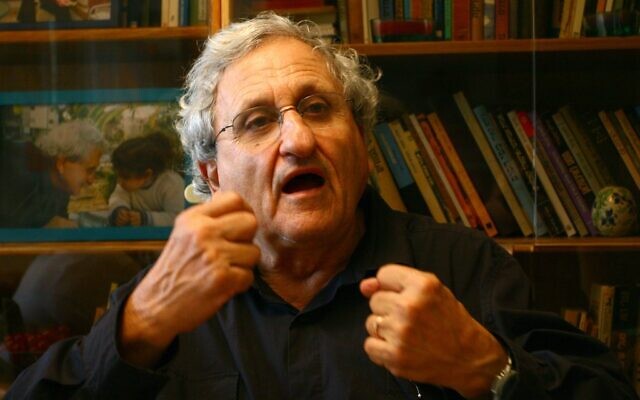

Israeli literary giant dies aged 85

Influential author, recipient of the Israel Prize and dozens of other awards, A.B. Yehoshua was also known as a sharp-tongued orator and staunch Zionist.

Abraham Gabriel Yehoshua, known to many Israelis as Buli, a fiery humanist, towering author, and staunch advocate of Zionism as the sole answer for the Jewish condition, died Tuesday.

He was 85 years old.

A writer, essayist, and playwright, Yehoshua was the recipient of Israel’s top cultural award, the Israel Prize, in 1995, along with dozens of other awards, including the Bialik Prize and the Jewish National Book Award, and his work was translated into 28 languages.

Eulogising Yehoshua, President Isaac Herzog called him “one of Israel’s greatest authors in all generations, who gifted us his unforgettable works, which will continue to accompany us for generations.

“His works, which drew inspiration from our nation’s treasures, reflected us in an accurate, sharp, loving and sometimes painful mirror image. He aroused in us a mosaic of deep emotions,” Herzog added.

Prime Minister Naftali Bennett mourned Yehoshua as “one of the pillars of Israeli literature, a man whose words were read by many. He has left a crowd of readers full of admiration for the person who took a part in shaping the culture of the State of Israel. May his memory be blessed.”

Yehoshua’s work was structurally innovative and narratively traditional. There were no chapter-long sentences in his novels and no preposterous quests sapped of all plot.

Instead, one was likely to meet a raw exploration of a flawed but likable protagonist, a patient, humour-laden style, and a dark storyline that deftly held the reader to the page. The sentences were long and complex, nested with meaning, and the heart of the stories could often be found in dialogue. He spoke frequently and adoringly of William Faulkner as an example of an author he admired.

President of Zionism Victoria Yossi Goldfarb spent time with Yehoshua when he visited Australia.

“A.B Yehoshua’s passing is an enormous loss for the State of Israel, the Jewish world and indeed for the global literary community. He was a literary giant, often spoken about as a possible Nobel laureate, an activist and someone I’d consider as part of Israel’s moral conscience,” Goldfarb said. “I was privileged to spend two weeks with him in the 90s when he toured Australia, and I can also say that Buli was just one of the loveliest, funniest and smartest people I have ever met. A total mensch.”

Communications director at the Zionist Federation of Australia, Emily Gian, said, “I was first introduced to the works of noted Israeli author AB Yehoshua in my first year at University, and have spent my entire adult life writing about him.

“While my PhD on his writing has been sitting half-completed for a number of years, I could never really let go of him, and I always hoped I would get the chance to interview him and finish my tribute to his brilliance. He was a true literary giant and his passing is a huge loss for Israeli literature.”

Yehoshua was not always destined for greatness as a writer. In 11th grade, his only failing mark on his report card, a recent documentary revealed, was in composition.

But 10 years later, he released his first collection of short stories and was promptly hailed as a writer of great insight and skill. Amos Oz, at the time still an unpublished author, wrote in a biweekly literary journal, Min Ha’Yesod, that “Yehoshua’s unique trait is expressed in his ability to create scandalous situations… and situations akin to those in a crime novel… without ever slipping into the sensationalism that lies in wait in such situations.”

Oz, later to become a friend and colleague, summed up Yehoshua’s skill as an author by saying, “While the hammer is in hand, and its weight and strength are surprising, the anvil is still too narrow.” He urged him to widen the scope of his stories.

Which is precisely what followed, with his 1968 collection Facing the Forests.

Several of his greatest works arguably came to define the era in which they were published. Facing the Forests, released in 1968, at the apex of the post-Six Day War euphoria, is to this day widely seen as the most arresting exploration of the Palestinian Nakba in Hebrew literature, signalling an awakening among his generation. And his first novel, The Lover, published in 1977, managed to herald the seismic shift in Israeli society with the rise of the Likud party to power and the decline of the Labourite and largely Ashkenazi left.

His novels — The Lover, A Late Divorce, Five Seasons and Mr. Mani — were written either as a Rashomon or in sections, like a pack of tightly bound novellas, and were undoubtedly some of his best works.

The English-language cover of Mr. Mani, a five-part novel that moves backward in time, carries a succinct quote from Ted Solotaroff’s magisterial review in The Nation: “The Nobel Prize has been given for less.”

Mr. Mani, which is stunningly composed of five one-sided conversations, forces the reader to fill in the blanks in the dialogue. It also marked the beginning of Yehoshua’s exploration in earnest of Sephardic identity in his fiction, which was, at first, a theme he avoided.

Until he was told by S.Y Agnon – who was twice awarded the Israel Prize for literature and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1966 – that Yehoshua would do well to hew more closely to stories of his own kind, perhaps an old iteration of ‘write what you know’.

Yehoshua later explained on a podcast, that he was only able to delve into his Sephardic roots in his fiction after the funeral of his father. Standing there on the Mount of Olives, interring in the earth the man who had devoted so much of his life to preserving the stories of the old Sephardi families, he began to feel the story stir within him. “My cousin came up to me at the funeral and said he was ‘sleeping with his fathers,’” he relayed. The strange, nearly erotic biblical phrase, he said, is what “gave me the drive.”

Several years later, he released A Journey to the End of the Millennium.

Yehoshua was criticised for his take on Jews in the diaspora, saying all those who live outside the state of Israel were “partial Jews”. In 2006, he wrote: “I have no doubt that in the future when outposts are established in outer space, there will be Jews among them who will pray ‘Next Year in Jerusalem’ while electronically orienting their space synagogue toward Jerusalem on the globe of the earth.”

Tellingly, toward the end of his life, he chose to again address the theme of Diaspora Jewry in two works of fiction that have not yet been translated into English. In both HaBat HaYehida (The Only Daughter) and HaMikdash HaShlishi (The Third Temple), the story revolves around families, one in Italy and the other in France, that are part Christian and part Jewish.

His final work, The Third Temple, is written more like a play than a novel, portraying the daughter of a convert trying to convince the local rabbi to testify against her old rabbi in France. It ends with the woman placing a photo of the Old City of Jerusalem on the rabbi’s wall and pinpointing the exact spot where she’d like to have an alternative temple established, a place where “anthems of hope and redemption are sung” rather than what exists now: “a desolate wall, sprouting vegetation, a useless and un-glorious relic that stymies and obfuscates our path.”

And yet, the final line of the novel, a stage direction, shifts away from the centrality of the Temple and suggests that redemption perhaps lies elsewhere.

“He shuts the light. Complete darkness. But then at the far end, in the distance, the grocery store glows.”

It was, from the elusive Yehoshua, a wink and a final farewell.

With Times of Israel

comments