Pirkei Avot – Ethics of the Fathers

Pirkei Avot tells us that ethics, honesty, and advice regarding interpersonal relationships are intrinsic to Judaism.

A WELL known minhag that apparently dates back to Saadiah Gaon in the 10th century is the study of Pirkei Avot – Ethics of the Fathers – on Shabbat afternoons between Pesach and Shavuot.

Its six chapters – five Mishnaic chapters plus an additional chapter of similar origins – allow for study of one unit on each of the six Shabbatot during this period. And in many communities that study carries throughout the northern summer right up to Rosh Hashanah meaning completion of not one but four cycles each year.

What is Pirkei Avot?

The six orders of the Mishnah are a compendium of halachah – the earliest such compendium – compiled in the second century, just a few generations after the destruction of the Second Temple. Edited by Rabbi Judah the Prince, its purpose was to maintain for all generations the oral traditions that were in danger of being lost in the chaos and confusion of the post Temple era.

The six orders in which all laws were arranged are: Zeraim (agricultural laws preceded by the laws of prayer), Mo’ed (appointed times – Shabbat and festivals), Nashim (literally “women” but referring to all laws associated with marriage and divorce), Nezikin (damages – civil and criminal law), Kodashim (temple-related matters but also including shechitah etc) and Taharot (laws of ritual purity).

Pirkei Avot, dealing with ethics rather than halachah in the purest sense, was incorporated into Nezikin as its penultimate tractate (the last being Horayot dealing with the principles of teaching and ruling in regard to law).

Obviously the sages saw a need for ethical behaviour beyond the letter of the law as an essential component of the relationships between people prescribed in the rest of Nezikin.

And it is in that context that for us study of these ethical principles during this period serves as an introduction to Kabbalat haTorah – receipt and acceptance of the Torah – on Shavuot. One of the most oft quoted rabbinic aphorisms is “derech eretz kadma laTorah – derech eretz precedes Torah”.

The term derech eretz, in Chazal’s parlance, has multiple meanings but first and foremost, it refers to the notion of menschlichkeit – decency, common courtesy. Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch (Commentary to Avot 2:2) explains how the term is used in reference to “the paths of discipline with manners and refinement that social life require, and to everything that touches upon the development of humankind and civility”.

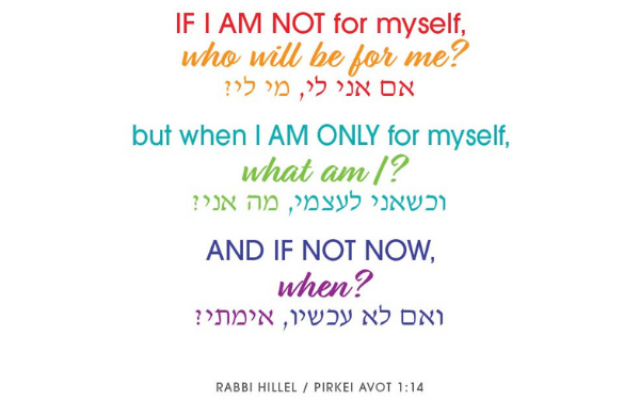

To many, emphasis on derech eretz so defined would almost seem trite, though in this day and age where some emphasise ritual and legalistic minutiae at the expense of such principles there is much to be said for referring back to derech eretz as a religious essential. However there is another element to note regarding the presentation of these principles in Pirkei Avot. The tractate begins by emphasising the Sinaitic origins of the oral law and all it encompasses, as well as the reality of mesorah – the fact that since Sinai there is an unbroken train of tradition through the Judges, Elders, prophets and the Men of the Great Assembly. As we then enter the era of the Sages we actually name leaders in each generation who accepted the tradition and through teaching continued the chain. And for so many of them we cite an aphorism particularly associated with their name. No wonder that this study is so broadly viewed as an essential prerequisite to all that Shavuot stands for with its emphasis on Torah law.

But there is also another aspect to be considered. Yes morality has a broader following than just among Torah-aware or Torah-observant Jews. But among Torah-connected Jews it is a fundamental principle that even moral principles – and the widely accepted basics of civil and criminal law (some of which are incorporated in what are broadly termed the seven mitzvot of B’nei Noach applicable to all humanity) are part of what we received at Sinai. The underpinning of all we do that is right can be traced back to that fundamental moment of Jewish history.

And perhaps just because every element of our lives is associated with Torah we end each session of study of Pirkei Avot with the well-known words of Rabbi Chananya ben Akashya: “The Holy One blessed be He sought to provide many (opportunities for) merits for Israel and therefore He gave them much Torah and many mitzvot.” If indeed every element of that which we practise in our lives is Torah related then indeed we have a constant opportunity to acquire merits. Hence also, given those opportunities, as we say in the introduction to each study session: “All of Israel has a share in the world to come.” For as the sages said elsewhere, (with every action a potential mitzvah) each Jew (even those termed sinners) is as full of mitzvot as a pomegranate has seeds.

Even if you have not followed this custom since the Shabbat after Pesach when the current cycle began, this Shabbat take the opportunity to study some Pirkei Avot and continue doing so in coming weeks. And if you worry about starting something you might not complete remember that: “Lo alecha hamlacha ligmor, v’lo atah ben chorin l’hivatel mimena – You are not expected to complete the task, but neither are you free to avoid it” (Rabbi Tarfon, Pirkei Avot 2:21).

Shabbat shalom,

Yossi

Yossi Aron OAM is The AJN’s religious affairs editor

comments