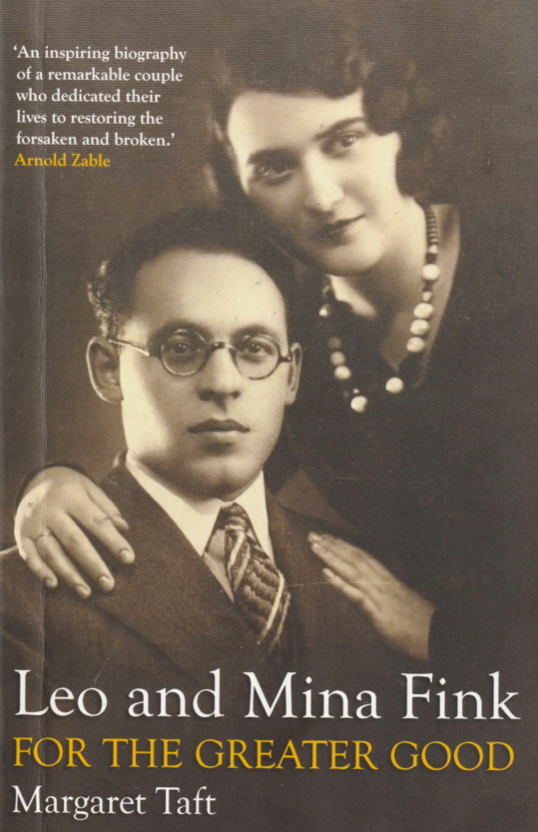

AUSTRALIAN Jewish academic Dr Margaret Taft’s odyssey into the life and times of Leo and Mina Fink – while she was in lockdown in 2020 – has culminated in her important biography, Leo and Mina Fink: For the Greater Good.

Researching Yiddish-speaking Melbourne with former colleague Dr Andrew Markus, Taft, the Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation’s research associate – and a child of Yiddish-speaking Holocaust survivors – became fascinated with the Fink name that pervades the Jewish community. “It really spiked my interest,” she says.

Her later research, while the COVID pandemic kept her within her four walls, revealed the Finks as a model of the courage and energetic chutzpah that characterised post-World War II Jewish communal pioneers.

Interviewed by The AJN, the Melbourne researcher describes Leo and Mina as “a power couple”. The phrase rings oddly for a husband and wife who lived their lives before that terminology became vogue. But it fits. “Part of Leo and Mina’s leadership skills was their ability to bring people along with them,” explains Taft.

They worked as a team, lobbying to bring homeless Holocaust survivors to Australia, building a support base to nourish this new cohort, and promoting Shoah remembrance. And Mina’s work with the National Council of Jewish Women of Australia (NCJWA) fostered a nascent Australian Jewish feminism.

Taft’s probing took her back to Poland at the dawn of the 20th century. Born in 1901, Leo grew up in Bialystok, then the most fervent centre of Jewish life in the world, with its heady blend of Yiddish culture, and a rainbow of synagogues and yeshivot.

In 1920, Leo journeyed to Mandatory Palestine, joining a pioneers corps building kibbutzim and digging irrigation channels. Returning to Europe, he studied civil engineering in Germany, then joined his family’s textile business in Romania.

Taft’s narrative then veers to left field – from Bialystok on one page of her biography, we are transported to Berwick, Australia on the next.

In 1928, inspired by an article on Australia, Leo and his brothers emigrated, establishing a Jewish farming settlement on the fringe of Melbourne. But later they returned to fabrics, setting up United Woollen Mills.

In 1932, during Leo’s visit to Bialystok, his mother played matchmaker, and he married a Bialystoker. Born in 1913, Mina Waks had been orphaned at eight and raised by her grandparents. “It was quite an extraordinary match, but they were great partners. I think they saw in each other what they needed in a relationship,” reflects Taft.

Returning to Melbourne, they prospered financially, and found time for the Jewish community. Leo became treasurer of Kadimah in 1938. The Yiddish cultural organisation was a platform from which he tried to democratise the Victorian Jewish Advisory Board (now Jewish Community Council of Victoria), at the time dominated by three Melbourne synagogues.

That year, Leo and Mina – by now parents of two young children – travelled back to Europe, and Mina revisited Bialystok. To the west, Hitler had annexed Austria. In hindsight, Mina’s visit had given her precious time in a world soon to vanish into the Nazis’ camps and crematoria.

“Poland was already crippled by antisemitism; it was not the country she had left,” says Taft.

With European Jewry sealed off, Taft says Mina “felt guilt-ridden” at what she did not – and could not – do: pluck out young members of her extended family and bring them to Australia.

During the war, Leo, now in the army reserve, became even more involved in Jewish life. Running the United Jewish Overseas Relief Fund, he merged it with the Australian Jewish Welfare Society to create the Australian Jewish Welfare and Relief Society, predecessor to Jewish Care. As pockets of Europe were liberated, Australian Jewish relief efforts joined those of other Jewish communities, with links to global Jewish aid organisations.

The welfare merger “was really a takeover by European-born Jews who had a different perspective on what welfare had to be and how quickly they had to move”, reflects Taft. “These were life lessons Leo and Mina had learned growing up in Bialystok, which was devastated in the First World War but was rebuilt by other Bialystokers … Jews had to help other Jews to survive. Leo and Mina believed they were links in a Jewish chain.”

Indeed, Leo and his contemporaries became a new voice for Australian Jewry. He engaged robustly with Arthur Calwell, immigration minister in Ben Chifley’s ALP government. The pugnacious Bialystoker pushed against a restrictive immigration policy.

After World War II, Australians understood the urgency to “populate or perish” in a region in which future invasion was a distinct possibility. But public xenophobia slapped boundaries around this.

“Calwell had an eye on his party, on the Parliament and on the public,” says Taft, noting the minister’s professed preference for “blond Balts” to swell Australia’s population.

So, for a democracy, Australia’s postwar immigration policy carried curious quotas. As ocean liners ploughed their way south from Europe, three quarters of each ship’s manifest had to be paying, non-Jewish passengers. The Jewish community had reluctantly agreed to no more than 3000 Jewish arrivals annually.

But Leo practised a plucky brinkmanship, pushing back at Calwell. In 1947, the Dutch steamship Johan de Witt knowingly and significantly exceeded its Jewish quota, but Fink gambled that Calwell would not turn back a ship carrying destitute Holocaust survivors. He won, drawing no more than a fierce rebuke from the immigration minister.

However, Leo had ruffled the feathers of the Anglo-Jewish establishment and had trodden on Victoria-NSW fault lines. In Sydney, Executive Council of Australian Jewry president Saul Symonds admonished him for insinuating himself into the Jewish community’s relationship with the government.

But this new breed of Australian Jewish leader had no patience for the genteel approaches of yesteryear. Leo was ready to scrap for the rights of survivors. Relieving the crowded DP camps and finding the homeless a home in Australia was urgent business, and he made it his own.

Bringing in Jewish refugees was only half the battle. Finding accommodation and paid work was a challenge. Housing was a thorny issue because of a shortage that saw returning Diggers waiting for a roof over their heads.

The Jewish community would look after its own, Leo assured Canberra, aware that much of the public’s fear – exacerbated by sensationalist, xenophobic media coverage – was that migrant Jews would become a public burden.

Mina Fink, meanwhile, had raised a corps of some 900 female volunteers she dubbed “my army”, which assembled relief packages for Jewish survivors in Europe. And she took a personal interest in the new arrivals, especially young orphans. Understanding personally what it meant to be an orphaned child, she arranged picnics and parties for these children, sometimes at the Finks’ seaside holiday house.

In the 1950s, as professional social workers became more common in Jewish welfare, she turned to another passion. In 1957, Mina became the first European-born head of NCJWA (Victoria). As national president in 1967-73, she pioneered projects in Israel. In 1987, she was elected as an honorary executive member of the International Council of Jewish Women.

Leo and Mina visited Israel numerous times. In 1963, his textiles venture in Ashdod became the first of its kind in Israel by an Australian businessman.

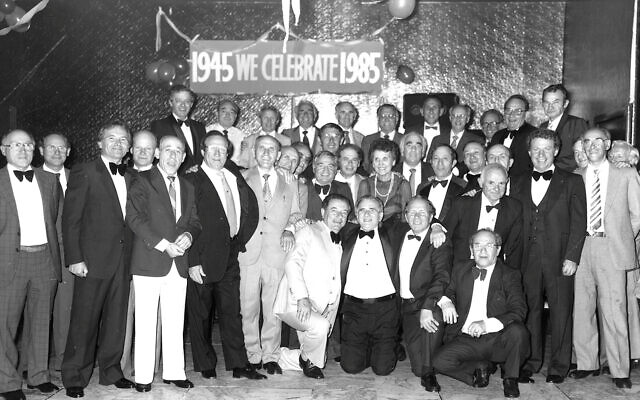

In later years, inspired by Melbourne survivor Sheva Glas-Wiener’s harrowing story of how she looked after Jewish girls at the Marysin orphanage in the Lodz ghetto, published as Children of the Ghetto, Mina became a major donor and passionate fundraiser for the Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC) in Melbourne, which opened in 1984.

“But Mina was insistent that the guides had to be professionally trained and that beyond remembrance, the museum had to carry a message to future generations, a message of tolerance and understanding,” says Taft.

Leo died in 1972 – and Mina survived him by 18 years, during which her role at the JHC flourished.

Working with a mass of documents and her notes from interviews with descendants, Taft first established a timeline of the Finks’ story. “But that was only the beginning of my research. I was intrigued by the ‘why’ of it. They had a comfortable life. What drove this couple to do the work they did? And how did they keep so much in lockstep with each other?”

Understanding that context “was the most satisfying part of the project”.

Leo and Mina Fink: For the Greater Good is published by Monash University Publishing, publishing.monash.edu. It was launched in March this year.

comments