IT was less than three months into David Friedman’s tenure as US Ambassador to Israel and he was already thinking big – about using his position to transform the Middle East.

He shared his plan with then-US president Donald Trump during a brief visit back to Washington in July 2017: “I want to move the goalposts back to where they belong with regard to the conflict and work with [senior White House adviser] Jared [Kushner] to perhaps make peace from the outside in – beginning with Israel’s natural allies. While the Palestinians are dysfunctional, there are Arab neighbours that may be ready to normalise with Israel.”

“Okay, go for it then. Good luck,” Trump replied, and with that Friedman returned to Israel and got to work, playing a central role in the president’s subsequent decisions to recognise Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and move the US embassy, recognise Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights and introduce an Israeli-Palestinian peace plan. All of these steps helped lead the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Morocco to agree to normalise ties with Israel in Trump-brokered agreements known as the Abraham Accords.

That’s the narrative Friedman builds in his new memoir Sledgehammer. But it’s one that contradicts other firsthand accounts and reporting on the formation of the Abraham Accords, which recall them as a last-minute change of course by the Trump administration after its controversial peace plan led then-Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu to declare that he had US backing to immediately begin annexing large parts of the West Bank.

Netanyahu’s announcement sparked furious reaction from across the Arab world. Fortunately for the Trump administration, it also gave Abu Dhabi the needed space to offer normalisation in exchange for halting annexation.

In Friedman’s telling, though, the accords were less a lucky break than a natural outgrowth of his years as Trump’s man in Tel Aviv and then Jerusalem. He succinctly explains how each accomplishment led to the next, thanks to his no-nonsense approach, which viewed the State Department he worked under as the heart of the “Deep State”, the Palestinian Authority as inept and full of empty threats, and the Arab world as a unit that “instinctively gauge[s] the strength of their opponents.”

To get things done under such circumstances, one needs to take a sledgehammer to old norms, the author says, explaining the title of the book.

The Trump administration indeed smashed through old norms, attempting to rebuild the contours of the Middle East’s messiest conflicts by fiat rather than consensus.

Friedman’s book takes the same approach, pulverising the more familiar narrative of the administration’s chaotic Middle East diplomacy into a flattened, linear and convenient account that’s not altogether convincing.

Along the way, Friedman sometimes clobbers through inconvenient facts to offer a view of his time as ambassador that portrays him in the best possible light.

To shed light as to why Trump so trusted his Israel envoy, Friedman begins the book with how they met in 2004. Friedman was at the height of his career as a New York bankruptcy lawyer and a mutual friend put him in touch with Trump to assist in “extricat[ing]” the real estate mogul from his casino albatrosses in Atlantic City.

Friedman managed to save Trump tens of millions of dollars, and while the businessman wasn’t thrilled about being charged a $5 million fee, he eventually paid up, telling Friedman, “You are the best lawyer I ever met and I should have known I could never get the better of you. Keep the money and thanks!”

An Orthodox Jew, Friedman places himself prominently within the view of Trump as a messenger of heaven, popularised by Evangelical Christians and other supporters.

“Looking back on those days, I can’t help but think that perhaps God was boosting my reputation with an individual who he knew would one day place me in a position of authority where I could perform God’s will,” he writes.

In a recent interview with The Times of Israel, Friedman said he asked Trump for a role in formulating his Middle East policy during the 2016 presidential campaign with the goal in mind of becoming Trump’s ambassador if he won.

His confirmation process was rocky, and in an effort to receive bipartisan support Friedman was forced to either soften or walk back some positions.

That meant apologising for having once called supporters of the dovish Middle East lobby J Street “worse than kapos”. Reflecting in Sledgehammer, Friedman refers to it as a “tactical mistake”.

Once in office, he describes setting out to shake things up against a cadre of State Department “elites”.

“I would have to fight against this establishment for every big win we had,” he claims.

With Friedman as envoy, the administration indeed changed considerably – often ignoring the advice and doomsaying of more seasoned diplomats and policy wonks – including by realising Israel’s dream of US recognition of Jerusalem as its capital.

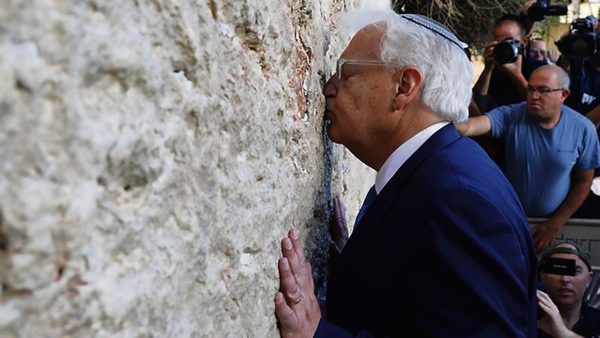

The US also closed its longtime consulate in Jerusalem, which for decades served as Washington’s de facto conduit for diplomacy with the Palestinians. Friedman and others have characterised the decision to close the consulate as necessitated by the embassy transfer, but he writes that he targeted the mission for closure years earlier, after one of its officials allegedly told a Shin Bet counterpart that the Western Wall is on occupied territory during preparations for Trump’s visit to the site in May 2017.

Friedman had a close relationship with Netanyahu, whom he describes working in tandem with to thwart PA President Mahmoud Abbas in a battle for Trump’s support during the president’s 2017 visit.

According to the former envoy, Abbas passed along a message to Trump that Ramallah would be willing to make major, never-before-agreed-to concessions in order to reach a peace deal.

Upon arriving in Israel, Trump asked President Reuven Rivlin why it was Netanyahu who was refusing to make peace. “That last comment knocked everyone off their chairs,” Friedman writes.

In an attempt at damage control, Friedman notified Netanyahu of the development and suggested the premier prepare a short video of remarks made by Abbas in which he allegedly incited violence against Israel.

The Israelis ran with the idea and Netanyahu showed it to Trump in their first meeting. The president was shocked and would go on to berate Abbas over the tape when they met in Bethlehem later that week.

Abbas, for his part, was said to have countered that Trump was being played: “You have the CIA. Ask them to analyse the film clips and you’ll discover that they were taken out of context or fabricated with the aim of inciting against the Palestinians.”

Throughout the book, Friedman appears to delight in pointing out the inaccuracies of others. But the book suffers from what appear to be errors or questionable claims on Friedman’s part, many of which end up undercutting the reliability of his other accounts.

Friedman writes that during his confirmation hearing, J Street spent nearly $100,000 on compiling a dossier of opposition research on him. But the left-wing group told The Times of Israel that it “did not spend a cent” on the research.

He refers to the West Bank settlement of Adam near Jerusalem as “perhaps the most liberal community in all of Judea and Samaria,” while speaking about a terror attack there.

In fact, voting records show Adam to be as supportive of right-wing parties as other settlements, if not more so.

He claims that US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declared settlements were legitimate, when Pompeo said that they were “not per se inconsistent with international law”.

Friedman mischaracterises Israel’s Supreme Court decisions on the Bedouin hamlet of Khan al-Ahmar as demolition orders, when the court only greenlit the demolition if the state chose to take that route.

Recalling a heated closed-door meeting with Senator Bernie Sanders during his confirmation process, Friedman says in the book that the Vermont lawmaker demanded a response within a week as to whether financial aid to Gaza was more important than aid to Israel.

Sanders’ foreign policy adviser Matt Duss declined to divulge the exact details of the private conversation, but advised taking the ex-envoy’s account with a grain of salt. Friedman, he says, lied under oath by vowing not to advocate for Israeli annexation of the West Bank, if confirmed.

Asked about the pledge, Friedman said he gave it in reference to annexation “on a standalone unilateral basis,” and indeed he did indicate it would have to be part of an agreement between “the parties” at the time.

His decision to back the move as ambassador, he said, was part of his support for the Trump peace plan, which offered marginal concessions to the Palestinians, such as the West Bank territory that remained after Israel would declare sovereignty over every one of its settlements as well as the entire Jordan Valley.

Friedman admits that he was initially hesitant about putting forth the peace plan due to fears that engaging with the Palestinians early on would require him to shelve his plans regarding Jerusalem recognition.

But as he tells it, the plan was just one of a number of diplomatic moves aimed ultimately not at peace with the Palestinians, but opening the Jewish state to the Arab world.

“Jared saw a real desire among the Gulf states to be further aligned with Israel, but they needed something that would give them diplomatic and political cover. We hypothesised that a ‘reasonable’ peace plan might provide that cover, even if the Palestinians opposed it,” he writes.

Friedman clearly left his mark on the plan, which envisions Israel annexing all Jewish communities beyond the Green Line so long as it agrees not to build in the remaining areas of the West Bank that the plan earmarks for a future Palestinian sub-sovereign state.

But the proposal’s architects neglected to include a timeline for when Israel could start annexing territory along the contours of the plan.

As Trump stood behind him at a White House ceremony to unfurl the plan, Netanyahu announced that Israel would annex all areas the peace plan envisioned as remaining part of the Jewish state. He told reporters immediately after the ceremony that he was going to bring the annexation plan to the cabinet for approval just five days later.

Shortly thereafter, the book recounts how Friedman got a call from Kushner: “Did you know that Bibi is annexing the freaking Jordan Valley today?”

According to Friedman’s account, he and Kushner went across the street to Blair House, where Netanyahu was staying, and proceeded to have “a difficult and unpleasant meeting.”

“Netanyahu said emphatically that we had a deal for immediate sovereignty. Jared responded that he thought the mapping process was a first step, which would take some time. To which Netanyahu responded that no mapping was necessary for the Jordan Valley. To which Jared responded, ‘We never discussed that’,” he writes.

Netanyahu was ultimately forced to cave.

The annexation timing ended up being a moot point, although, as on June 12, 2020, UAE Ambassador to the US

Yousef Al Otaiba penned an op-ed in the Yedioth Ahronoth Hebrew daily in which he warned Israelis that moving forward with annexation would squander a rare opportunity that was arising for Jerusalem to normalise relations with Abu Dhabi.

Kushner and Al Otaiba launched negotiations in the weeks that followed that led to Israel, the UAE and Bahrain signing the Abraham Accords three months later on the White House lawn, with Morocco joining the agreements shortly thereafter.

Yet, Friedman rejected the implication that the Abraham Accords were born in the final months of the Trump administration, thanks to the opening created by Al Otaiba.

Al Otaiba’s op-ed “was a public airing of discussions that had been taking place for years” between Trump officials and their allies in the Gulf about the possibility of normalising ties with Israel, Friedman said last week.

However, the former ambassador acknowledged that he and his colleagues in the administration did not know how such improved relations would look and for the first two years, they accepted the conclusion of former secretary of state John Kerry who said that the Arab world would not agree to fully normalise relations with Israel before the Palestinians were given a state of their own.

As US ties warmed with both Israel and the Gulf states, the administration came to reject Kerry’s assumption and began envisioning something bigger, said Friedman.

Still, it was the step by Al Otaiba that provided the clarity the Trump administration needed for how to act next. Would the UAE ambassador have taken that step if not for the US moves orchestrated by Friedman? Sledgehammer answers that question with an emphatic “no” and even has someone willing to stake his reputation in defence of that narrative, as opposed to other, less rosy accounts that frequently rely on anonymous sourcing.

But given the manner in which the former ambassador lays out his description of events, readers are left not really knowing whom to believe.

TIMES OF ISRAEL

comments