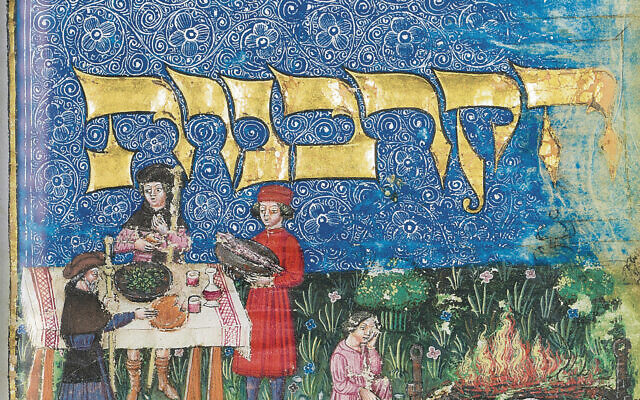

The Pesach seder through the ages

It’s about our history – but it has a history of its own.

WHILE starting with “Arami oved avi – a wandering Aramean was my father,” there is much history in the Haggadah, the seder night is not a time for simply talking about events past.

“Bechol dor vador chayav adam lir’ot et atzmo k’ilu yatza miMitzraim – in every generation one is obligated to view oneself as if he or she went out of Egypt.” Every day of the year there is a mitzvah to remember the Exodus. But on seder night we need to experience it – to be part of events that still have continuity and affect us accordingly. The specific seder observances are designed to achieve that end.

Nevertheless if seeking a historical approach to the seder, one can certainly talk about the history of the seder itself and the practices enshrined therein.

As the Rambam points out in Mishneh Torah (Hilchot Chametz u’Matzah 8) the focal point of the seder is the korban Pesach eaten with matzah and maror – the Pesach sacrifice whose roots date back to Pesach Mitzraim, the very first Pesach on the night that preceded the Exodus itself. It is, he adds (8:8-9), only in the (unfortunate) absence of a korban Pesach in this day and age of galut that it is replaced with a piece of matzah – the afikoman. So let me briefly encapsulate the history of Pesach night observance as per the books of the Tanach.

Clearly the first reference and first occasion on which consumption of the Pesach sacrifice with matzah and maror took place was that night of “makkat bechorot – the slaying of the first born” that did not affect Jewish houses which had the blood of the sacrifice on the “mezuzot”, the door posts. Nevertheless there appears to have been a precedent 401 years earlier – at least for matzah if not the Pesach lamb itself. For when the angels came to Avraham to advise that a year later his son Yitzchak would be born, we find that Avraham instructed Sarah “looshi v’asi ugot – knead dough and make cakes”(Bereshit 18:6). That word “ugot” is the same word used in Shemot to tell us that on departure from Egypt they baked “ugot matzot – (round) cakes of matzah” (Shemot 12:39). And in fact the next night, when the angels were in Sodom to warn Lot to leave, we read that: “Matzot affa vayochelu – he baked matzot for them and they ate” (Bereshit 19:3). Having lived with Avraham for so long he was apparently aware of Avraham’s practices.

Following the Exodus, the next recorded instance of a Pesach sacrifice occurred just one year later. This is the famous occasion when some who were unclean as a result of contact with a dead person (the bones of Joseph carried through the desert) and therefore unable to carry out the observance, complained that it was unfair that they be excluded from so important an event. The outcome was the institution of Pesach Sheni (a second Pesach), a provision that one who was unclean (or far from the Temple) on Nisan 14 could carry out the observance a month later on Iyar 14.

Forty years after leaving Egypt Israel crossed the Jordan and entered their land on Nisan 10 – the exact 40th anniversary of the date that prior to the Exodus they were to take a sheep, bring it into their house and prepare for the sacrifice on the 14th. And as we read in the haftarah of the first day of Pesach, now too the 14th of Nisan saw observance of the Pesach – this time in their homeland (Joshua 5:10).

One might have thought that following that precedent whereby amidst what must have been euphoria on finally entering the land they celebrated with remembering their origins, Pesach would immediately become an anchor of observance by the nation now in its land.

However it seems that once Israel settled in its land and even after the Temple was built, Pesach was not always properly observed. In Divrei Hayamim (Chronicles) II (30) we find that King Hizkiyahu instituted a Pesach celebration that had not been matched since the days of King Solomon – but was on Pesach Sheni, not Nisan 14. However finally as regards specific references in the Neviim (Prophets) section of Tanach we come to the Pesach in the days of King Yoshiyahu, the subject of the haftarah of the second day of Pesach. Apparently by this time much Torah had been forgotten and the King now read in the ears of the men of Judah the words of the “book of the covenant” that had been found in Temple. “And the King commanded all the people saying: ‘Make the Pesach offering to the Lord’. Indeed such a Pesach had not been held since the days of the judges – and all the days of the Kings of Israel and Judah. Only in the 18th year of King Yoshiyahu was this Pesach celebrated to the Lord in Jerusalem” (Kings II 23:21-23).

Moving to the Second Temple era, we read in the book of Ezra (6:22) that just three weeks after completion of construction of the second Temple on Adar 23, Pesach was observed – rightly the first mass celebration in a new era. After all once again the Jewish nation (or at least part therof) had left exile for their land.

Post the Tanach era, Jewish-born Roman historian Josephus Flavius records the extent of observance of the Pesach pilgrimage and sacrifice in the Roman era prior to the outbreak of the wars that led to the destruction. Even from the Babylonian golah tens of thousands made the pilgrimage and offered the Pesach lamb in the Temple. While we have no evidence as to how their seder was actually performed, we know from the story of the five rabbis as recounted in the Haggadah that in the immediate post Temple era the seder was observed in a lengthy discursive context in a manner parallel to ours. And of course the final chapter of Mishnah Pesachim already presents us with the text of the Haggadah with which we are familiar – a presentation of text in a form that we recognise that predates almost everything else in our prayer rituals except actual quotations from the Torah such as the biblically mandated recitation of the Shema.

Indeed as we proceed with our sedarim we are simply continuing a tradition of millennia through which we too like our predecessors hopefully continue to experience that which was the experience of our forebears as they departed Egypt from slavery to freedom.

Shabbat shalom,

Chag Kasher vesameach

Yossi

Yossi Aron OAM is The AJN’s religious affairs editor.

comments