The reality of apartheid

It is not for Human Rights Watch or any other self-important agency to re-word the definition of apartheid to suit its ends.

MY wife and I lived in a modest apartment block in the Johannesburg suburb of Yeoville in the 1980s. At 6pm every evening a nightwatchman came on duty. His name was George and he sat in a corner of the foyer for 12 hours, his responsibility being to keep us safe. He had done this unfailingly for three years. One evening, George didn’t show up. A black man in his 50s, he had been arrested. His crime – not having his identity card, called a pass, in his possession when arbitrarily stopped by a policeman.

This was common practice, designed to enforce the apartheid government’s politically and racially motivated policy of social engineering which ensured that the movement of South Africa’s blacks – and their presence in urban areas – was controlled and contained. The Pass Law gave blacks permission to be in a particular place at a particular time – but only in that place and for not a minute longer. Failure to meet those conditions, or inability to produce a pass on demand, meant immediate incarceration, invariably after being tossed into the rear of a police van.

George had been locked up at the nearby Hillbrow Police Station. Racing to get there in time to offer support when his case came up, I found almost 100 black adults seated there, all under arrest for not having their pass in their possession when stopped by police while going about their business.

I missed George’s hearing. It had taken a matter of minutes, with imprisonment the automatic outcome. Knocking on every door of our apartment block that night in what proved to be a fruitless attempt to raise bail money, just two of the 60 residents were willing to contribute.

A minor anecdote? Perhaps. But a telling symptom of the inhumane conditions which prevailed from 1948 – when National Party leader Daniel Francois Malan was elected president, ushering in the apartheid era under the deceptively benign rubric of separate development – until 1994, when Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela became the first president elected after all South Africans were granted the vote.

It was a grotesque system of government at both the personal and political levels, with unmitigated racism the thread which connected and permeated both strands. It was predicated on three cornerstones:

• The Race Classification Act, which classified and separated the population according to colour – whites and so-called non-whites, the latter grouping comprising, in “descending” order, Asians, so-called coloureds (people of mixed race) and blacks.

• The Mixed Marriages Act, which prohibited marriage and sexual relations between the races.

• The Group Areas Act, which stipulated where races could live, the Pass Law a key instrument of this legislation.

APART from the inhumanity of the system, it also had bizarre applications. Chinese South Africans, for example, were classified as Asian and therefore non-white, while Japanese South Africans were classified as honorary white, the rationale presumably being South Africa’s pursuit of trade relations with Japan.

Soweto – an acronym for South West Township – was a sprawling informal city on the edge of Johannesburg which was shockingly deficient in basic amenities such as water, street lights and toilets. It was mainly populated by two million black men, whose presence – indeed, existence – had one purpose, and that was to mine the massive quantities of gold below the ground, providing the nation with a major source of foreign exchange.

Under a clause known as Influx Control, the mine workers were prohibited from having their families with them, the latter banished to Homelands or Bantustans – largely impoverished areas to which most blacks were confined. If caught bringing their families to live with them, the men were charged with harbouring their wife and children. The unnatural conditions, which denied the teeming populace normal human interactions, were conducive to high crime rates.

South Africans classified as non-white had no right to vote or run for political or public office. There were separate hospitals, schools, train carriages, buses, sports clubs, beaches, swimming pools, cinemas, restaurants, park benches, toilets and entrances to the post office – all designated “Whites Only” or “Non-Whites Only” in English or Afrikaans or both.

There were even separate ambulances, which meant “Whites Only” ambulances were prohibited from stopping at the scene of an accident to attend to injured “non-whites”.

There was more, out of sight of the public. The government annually allocated about 400 rands to the education of each white school student, compared with an insulting 40 rands for the education of each black student, ensuring the continued subjugation of the majority black population in terms of educational or career advancement.

There was the Information Scandal. Aware that most English-speakers and English-language newspapers opposed apartheid to a greater or lesser degree, the government siphoned 64 million rands of public money from its defence budget and established the Department of Information, the objective being to purchase media outlets in the US and Europe and turn them into pro-apartheid organs. It also set up a pro-apartheid English-language South African newspaper, The Citizen.

As chief sub-editor of The Cape Times, I was inevitably involved with the system, given the draconian mass of legislation restricting what media could publish. Most activists working to overturn apartheid were banned, which meant it was illegal to quote them or their aims. The effect was to render Mandela and others invisible – unless a courageous politician such as Helen Suzman, who was pilloried by the government for being progressive, female and Jewish, used parliamentary privilege to report her latest visit to Mandela in his Robben Island prison and the media covered her speech. And then there were the many – unrecorded or denied – incidents in which anti-apartheid activists were arrested, interrogated, murdered or hanged. By security agents. The most high-profile was Steve Biko – a potential Mandela. Articulate, charismatic, courageous. A leader of the Black Consciousness Movement, he was banned, arrested, driven naked in the back of a van for 14 hours, interrogated and beaten to death. One medical report said he sustained a “contra coup”, meaning his head was struck so forcibly that his brain moved from one side of his skull to the other.

Writing a book on South African history at the time, I was advised to delete the chapter on Biko out of concern that the entire book would be banned.

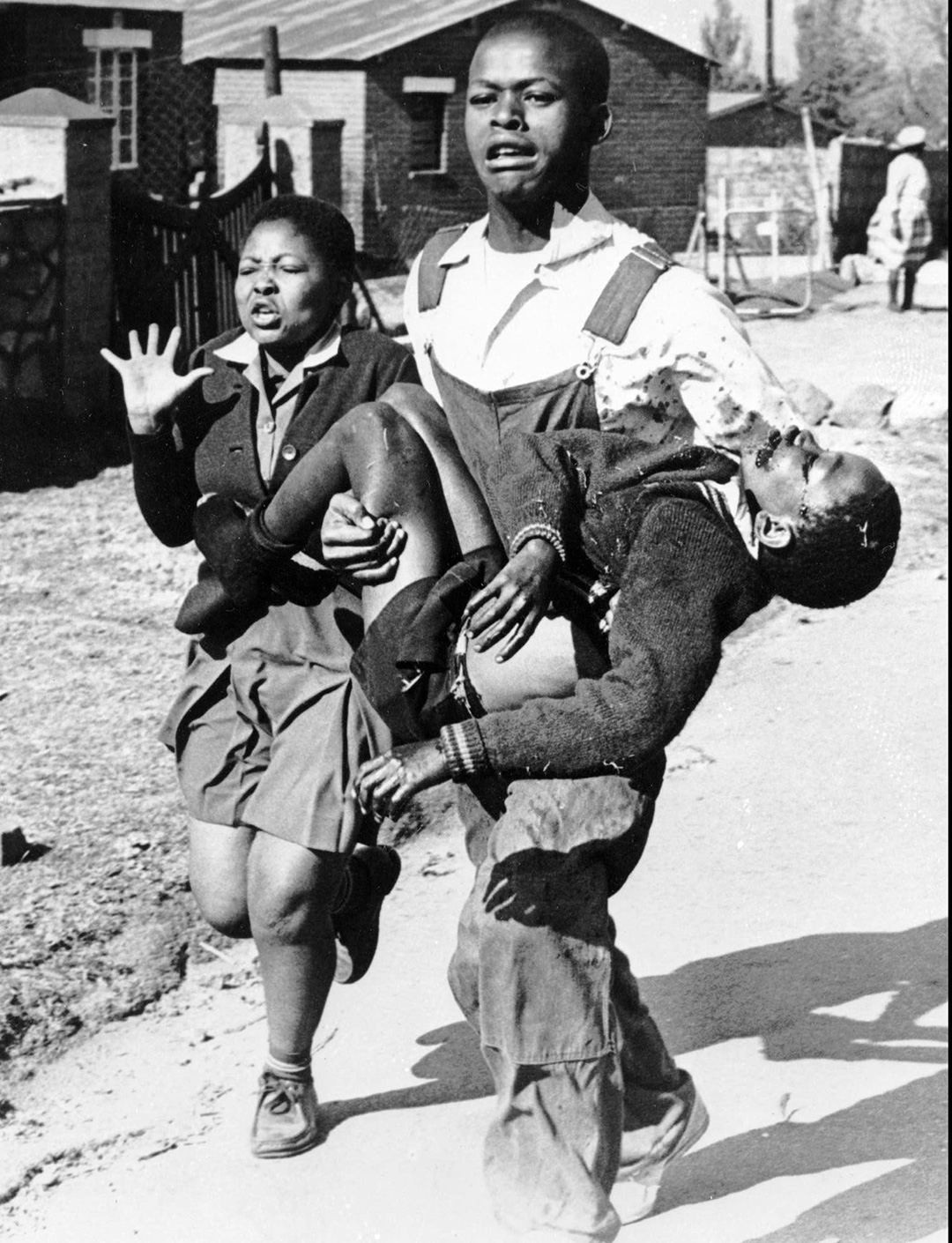

Nor can one overlook the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, when 69 blacks were killed by police – most shot in the back – while protesting the Pass Law; or the 1976 Soweto riots, when over 360 blacks were killed while protesting the introduction of Afrikaans as the medium of instruction at school.

South Africans in March 1960 protesting the Pass Law. Photo: Getty Images

THE objective of this overview is to depict the apartheid system from the perspective of one who was there. It is prompted by a 60,000-word report by Human Rights Watch (HRW), which invoked the apartheid slur to condemn Israel. Yet HRW admits it did not apply the textbook definition of apartheid when accusing Israel of that crime. Which means the only way it could make the egregious claim was by creating its own politically-motivated definition – a farce if ever there was.

Apartheid was apartheid was apartheid. It is not for HRW or any other self-important agency to re-word the definition to suit its ends. In fact, its own “definition” is so broad that if applied rigorously, almost every person in every nation could be deemed guilty of it.

Finally, no nation is faultless. It is simply relevant to note that there is only one country in the Middle East in which the rights of workers, trade unions, women, LGBTIQ people and ethnic and religious minorities are respected in a way that is consistent with democratic values and practices; that Israel’s Jewish, Arab and other citizens share the same hospitals, universities, public transport, beaches, shopping malls and other public spaces. Most significantly, every Israeli citizen has the same civil and religious rights, including the right to vote, and there have been Arab members of every Israeli parliament since the state was established in 1948 – the most democratic right of all – with 14 Arab members sitting in the current parliament.

The situation in the West Bank is more complex. Mahmoud Abbas is in the 17th year of his four-year presidency of the Palestinian Authority, which controls the major urban centres known as Area A. Israel controls the thinly-populated Areas B and C, but has not asserted its sovereignty over any of Areas A, B or C.

On the contrary, it has tabled at least three offers that would have established a sovereign, territorially-contiguous Palestinian state over 100 per cent of the Gaza Strip and more than 90 per cent of the West Bank, plus additional territory from within pre-1967 Israel to bring it to 100 per cent. Never did South Africa’s apartheid government contemplate anything that fair-minded.

The apartheid slur is baseless and a lie.

Vic Alhadeff is a consultant to the Executive Council of Australian Jewry and the NSW Jewish Board of Deputies.

Get The AJN Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

comments