A fresh perspective on children and rebellion

'Let us step inside our own childhood and consider our own behaviours'

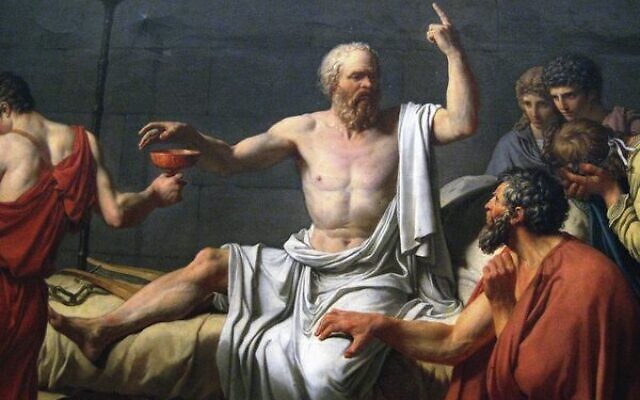

hildren: they have bad manners, contempt for authority; they show disrespect for elders and they love chatter in place of exercise … they contradict their parents and tyrannise their teachers.”

Who is the author of this damning condemnation of the younger generation? Is he a grandparent or parent of today, or maybe an exhausted teacher? Is she a minister in the government, or an expert in parenting or education? Alas, none of these. These are the words of the Greek philosopher Socrates, around 2500 years ago.

In our own tradition, we do not shy from the strongest reactions to the rebellion of youth. The Haggadah tells us, in response to the insolence of the rebellious child, quite literally to “blunt his teeth” (or in practice, punch him in the face).

The Torah goes one step further. The book of Devarim (Deuteronomy) says that a rebellious son (who may also be a drunkard and/or a glutton), for whom repeated chastening from parents and even elders has been unsuccessful, may be stoned to death.

Crikey. While the rabbis have of course interpreted, reinterpreted and softened this instruction – as they have with all other capital crimes – what are we to make of the propensity of the youth to rebel, and of the older generations to despair of their children?

Are we as parents and grandparents destined to repeat the cycle, forgetting that we were once ourselves the youth who were the cause of the despair of our elders? As the poet Philip Larkin said in one of his bleaker poems about childhood and parenting, “Man hands on misery to man.”

As a learning community that was the research base for the now world-renowned approach to teaching and learning Cultures of Thinking, my own school Bialik College revels in “thinking routines” to extend our children’s thinking at every opportunity. To paraphrase one of these routines, Step Inside, let us step inside our own childhood and consider our own behaviours.

Was it not our role as children and young adults to push the boundaries, to extend the thinking of our elders into new (or what we thought were new) inclusive and societally critical ways? Was there a time in our own childhood when we embraced new technologies to the despair of our parents? Did we ever do things that were naughty, rude, rebellious or disruptive?

I hope that you, like me, are able to answer yes to all of these questions.

After all, would the Civil Rights movement have ever got off the ground without the involvement of the youth? And what of the suffragettes, the chartists, the anti-apartheid and the gay rights movements? It is precisely because the young are willing to rebel against their elders and their norms that change has happened. Cultivated agitation is a fundamental right and expectation of the young.

What of naughtiness, rudeness and disruption? Do we forget sometimes that children are at the same time citizens from birth whilst also being unformed adults? Children are learning how to adapt and how to rebel and challenge respectfully. A short while ago I walked into a class whose teacher was running late. The students were being rather loud. Once I settled them down, I exclaimed, “My goodness, you are behaving like…” and I paused realising what I was going to say, until a child finished my sentence for me: “… children!” And we all laughed at the irony.

Indeed, children, like adults, frequently get it wrong. Consider the reference to “zero tolerance to bullying” in many a school’s behaviour code. What does that actually mean? Of course, schools – like all institutions – have red lines, after which it may be appropriate to end a relationship with a stakeholder, in our case children and their families. Yet on a micro level children will get it wrong, they will say the wrong thing and do the wrong thing. That’s why they are children. So if “zero tolerance” means a child is expelled every time they get their interactions with others wrong, how does that help perpetrators to amend their behaviour, and how does that help everyone to learn how to negotiate challenging situations, inappropriate behaviours and poorly behaved people?

The Jewish concept of teshuvah is often translated as “repentance” but in fact it means “return”. Our Jewish lens encourages us to return to situations where we have made mistakes, and then go on to repair relationships and fix them. Teshuvah is inherently restorative, and inherently sympathetic to the necessary flaws of humanity.

So what to make of all this rebellion, disruption and challenge? Maybe we need, as our teenagers would say, to take a chill pill. The cycle of life is indeed a cycle. In the words of Kohelet (Ecclesiastes), “There is nothing new under the sun.”

And as a final thought, let us consider technology. How many parents have despaired at their children’s addictions to the iPad, the Xbox or the Playstation?

Consider the words of this parent also in despair: “For this invention will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it … [it] offers the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom, for they will read many things without instruction and will therefore seem to know many things when they are for the most part ignorant.”

Who was this? A parent bemoaning social media? A teacher bemoaning the internet?

No, it is our old friend Socrates, 2500 years ago, bemoaning the invention of writing.

Jeremy Stowe-Lindner is principal of Bialik College Melbourne and is a philosophy and history teacher.

comments