When I was a boy, growing up in Melbourne and attending Mount Scopus College, we learned nothing about Australia’s Indigenous history.

I was not aware of having met an Aboriginal person until the 1990s, when my firm started to advise the Yorta Yorta peoples in their epic struggle for native title. Three decades later, they remain our clients and friends, alongside many other Indigenous businesses and community organisations.

It was around the time we took up the Yorta Yorta case that I heard the story of William Cooper, the great Yorta Yorta leader, who devoted his life to fighting for the rights of his people, and for all marginalised peoples.

Today, his name is recognised and admired by Jewish Australians for his actions in leading a march to the German Consulate in Melbourne in December 1938 in protest against the Nazis’ mistreatment of the Jewish people.

The story of the stand William Cooper took on behalf of our people hit me like a bolt of lightning. And I vividly remember travelling in a car with the lead Yorta Yorta claimants, Monica Morgan and Uncle Henry Atkinson, shortly after, and telling them of the wonderful piece of history I had just learned.

As it happened, William Cooper was Monica’s grandfather.

He had helped us in our time of need, and I assured Monica that my firm and I would be there for her and her people for as long as it takes.

It had taken me 50 years to realise the extent of the continuing injustice Indigenous Australians were suffering, how they had been scarred by dispossession, disrespect and racism – the same weapons that have been used against the Jewish people for millennia.

“If we had been listened to, and if policies had been designed in partnership with local communities to tackle the underlying disadvantage, then perhaps many of the issues that have erupted now would not have occurred.” Northern Territory MP Marion Scrymgour

My sense of the ties between the Jewish people and Aboriginal people grew even stronger through my friendship with Noel Pearson.

When Noel graduated from university, he came to work for me. And he’s said many times over the years that the time he spent at Arnold Bloch Leibler taught him how much our two peoples have in common.

Noel says his main take-out from working with me and meeting many Jewish Australians was that, like us, Indigenous people can and must resist victimhood, as Jewish people have done, even in the face of persistent racism and victimisation.

This is where the Voice to Parliament comes in.

While there will always be a diversity of views within any community, my sense is that the Australian Jewish community broadly supports the Voice as a just and reasonable step towards righting past wrongs.

However, I’m finding myself more regularly approached at functions and via email by people with questions – questions they want answered for themselves but also so they might help to educate others and build momentum towards a successful referendum.

Let me be clear, people who have questions and/or doubts about the Voice – at least the vast majority – are not racist. This is not about racism.

But keep in mind that, just as we bristle when other sections of the Australian community try to dictate to us what antisemitism is and isn’t, or how we should feel about the Holocaust 70-plus years down the track, we should respect, trust and support Indigenous Australians to determine the best approach to healing their wounds.

And they have determined that a representative body that can advise the Parliament and government of the day on laws and policies that affect them is the most meaningful step the nation can take at this time.

I hope this article, which covers a few of the foundation questions I’m most often asked, will equip people to play an active role in ensuring that family, friends and colleagues can make an informed decision later this year at the ballot box.

Let me be clear, people who have questions and/or doubts about the Voice – at least the vast majority – are not racist. This is not about racism.

Because, as the Shadow Minister for Indigenous Australians, Julian Leeser, said recently: “We have to get this right because the prospect of failure is unthinkable.”

There is a famous quote from the prophet Jeremiah that references a voice, and it comes to mind as we contemplate this step:

“A voice is heard, crying, weeping. It is a mother, Rachel, crying about her children; inconsolable because her children are gone.”

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice needs to be heard because our Indigenous children are suffering also.

And the words of the prophet tell us why.

Calm your weeping – as there is hope for your future.

The big questions

Why is constitutional recognition of our First Peoples important?

Firstly, we are privileged as Australians that our history encompasses the most ancient, enduring culture on earth. Surely, our founding document should recognise and celebrate this richness.

The other main reason is that while Australians of today are not responsible for past wrongs, we are responsible for recognising the impact of intergenerational trauma and for supporting Indigenous fellow citizens to heal from this trauma so that it doesn’t negatively impact generations to come.

Ever since John Howard announced during the 2007 election campaign that, if re-elected, he would work towards constitutional recognition, the aspiration has been embraced by every subsequent government, regardless of its political persuasion.

Having been closely involved in the journey towards constitutional recognition for well over a decade, I view the model we will vote on at the referendum as conservative yet meaningful – the best of both worlds.

How did the Indigenous Voice to Parliament and the executive become the form of recognition to be put to the Australian people even though it would have been far easier to attract community support for a preamble?

While each of the past seven Australian governments has advanced constitutional recognition, the last three have also understood that to pursue a referendum proposal that does not accord with the wishes of the people we seek to recognise would be inconceivable.

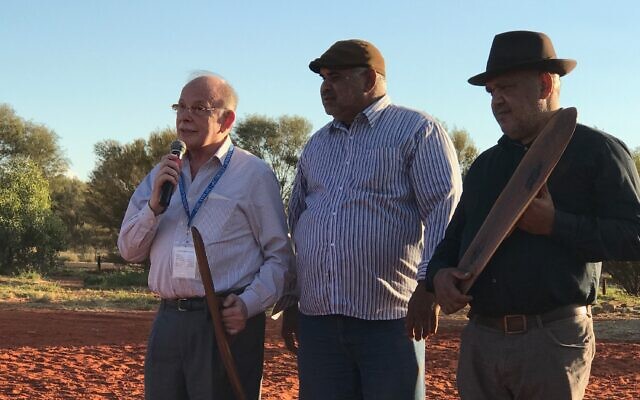

This is why former PM Malcolm Turnbull and then opposition leader Bill Shorten appointed the Referendum Council, which I co-chaired. Our terms of reference required us to consult specifically with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with a view to reaching broad agreement on how they might be recognised in the Australian Constitution.

An advisory Voice to Parliament, protected by the Constitution, was the model that flowed from the most proportionately significant consultation process that has ever been undertaken with Indigenous Australians in the nation’s history.

While other processes to advance constitutional recognition consulted with Indigenous people, this was the first time it was done systematically, comprehensively and in accordance with cultural protocols.

The integrity of the outcome was validated by the findings of the Joint Select Committee, co-chaired by the Liberals’ Julian Leeser and the ALP’s Patrick Dodson, which found that the Voice was the only form of recognition that would be supported by the people we seek to recognise.

Wouldn’t the Voice amount to a third chamber of Parliament and upend the smooth operation of our democracy?

What is proposed is a Voice to Parliament, not a Voice in Parliament. Former PM Malcolm Turnbull and the Nationals’ Barnaby Joyce once described the Voice as amounting to a third chamber but have both since admitted they were wrong.

The proposed constitutional amendment simply states that the Voice “may make representations” to Parliament and the executive government. It will be up to Parliament to decide what it does with those representations.

Parliament debates and formally enacts legislation but the executive does most of the policy formation before laws are enacted and most of the implementation after.

Why should the Voice be enshrined in the Constitution rather than legislated?

First Nations people want the Voice to be in the Constitution so that it cannot be abolished at the whim of a government, as other Indigenous bodies have been in the past. But only the principle of the Voice will be in the Constitution – all the detail about its form and function will be legislated by the Parliament and amended by legislation if and when required.

More important, though, is the fact that by providing for the Voice in the Constitution, the Australian people perform an act of recognition of the First Peoples of our continent.

How would it make a difference to the shocking circumstances of too many Indigenous Australians?

The main lesson governments, businesses and not-for-profit organisations have learned from decades of policy failure in working to improve the circumstances and life opportunities of Indigenous Australians is the imperative of working in close, respectful partnership.

The “Canberra knows best” approach has been poorly targeted and disempowering, wasting lives, potential and many billions of taxpayer dollars on ineffectual programs. This is why First Nations people want, need and deserve a Voice.

Referring to the current crisis in Alice Springs, Northern Territory MP Marion Scrymgour explained: “If we had been listened to, and if policies had been designed in partnership with local communities to tackle the underlying disadvantage, then perhaps many of the issues that have erupted now would not have occurred.”

Shouldn’t Australians have more detail about what the Voice will look like before the referendum?

In announcing the final wording of the referendum question and constitutional amendment, the Referendum Working Group also released a set of clear principles that will underpin the shape and function of the Voice.

But let’s be clear – the only thing the electorate will be asked to support at the referendum is the principle of the Voice, with all the detail left to the Parliament to determine. This detail that can be changed by the current and/or subsequent parliaments if the need arises. To suggest otherwise is to mislead the electorate into believing that we are being asked to vote for a particular model.

How can non-Indigenous Australians vote YES when some high-profile Aboriginal leaders are advocating a NO vote?

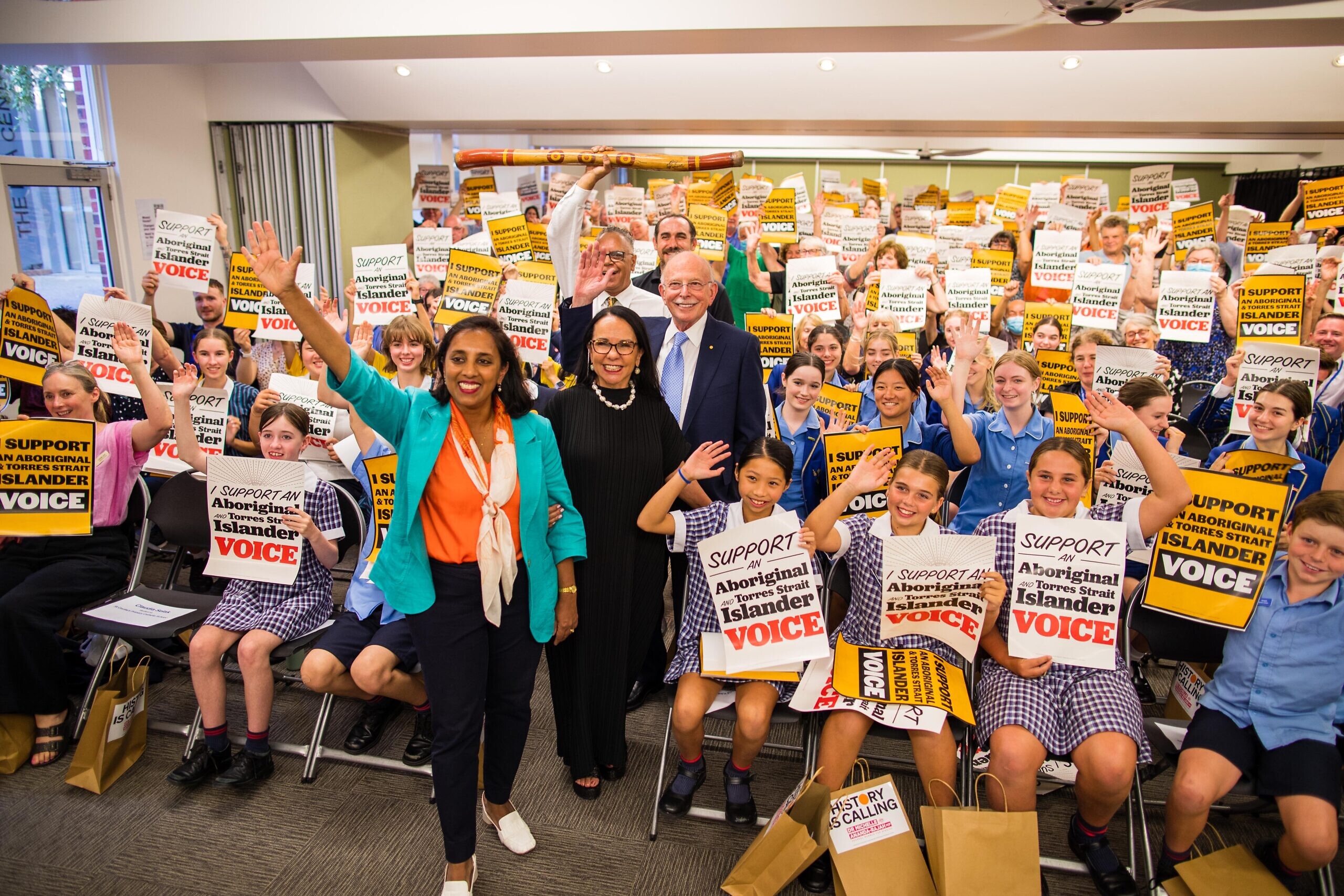

No proposal will ever attract 100 per cent support and no group of people will unanimously agree on anything. But the Voice to Parliament was the agreed outcome of an unprecedented consultation process with Aboriginal and Torres Strait lslander Australians, engaging a greater ratio of the population than the constitutional convention debates of the 1800s, from which Indigenous peoples were entirely excluded. Recent polling confirmed that 86 per cent of Indigenous Australians back the Voice.

Isn’t it racist and divisive to single out one group of Australians in this way?

As former High Court Chief Justice Robert French has recently pointed out, the Voice is not about race. It is about recognising our First Peoples as the indigenous peoples of Australia.

The claim that the Voice amendment would introduce race into the Constitution and assign “special treatment” to one group of Australians was contextualised in 2019 by another Chief Justice, Murray Gleeson, when he noted: “The division between Indigenous people and others in this land was made in 1788. It was not made by the Indigenous people. The race power in the Constitution is now used in practice to make special laws for them. The object of the [Voice] proposal is to provide a response to the consequences of that division.”

Would the constitutionally enshrined right for the Voice to make representations to Parliament and the executive result in inevitable, drawn-out litigation?

Former Chief Justice Robert French recently explained: “There is always the possibility that someone, someday will want to litigate matters relating to the Voice … that said, there is little or no scope for any court to find constitutional legal obligations in the amendment. And if Parliament made a law which created unintended opportunities for challenges to executive action, the law could be adjusted.”

Given the poor success rate of referendums in Australia, why are we taking this risk?

The most successful referendum in Australia’s history was the 1967 referendum in which more than 90 per cent of Australians voted YES to amending sections of the Constitution that specifically discriminated against Indigenous Australians.

Since then, the High Court’s Mabo decision overturned the fiction of terra nullius, and the National Apology allowed Australians of today to express their sorrow for past wrongs and First Nations peoples to accept that apology.

Constitutional recognition in the form favoured by Indigenous Australians would establish a new framework for dialogue and potential for a better future.

Aboriginal lawyer Teela Reid made a compelling argument at the Arnold Bloch Leibler forum last year – that everything meaningful carries a risk but the greater risk is not giving this a go, and a red-hot chance of success.

Mark Leibler is senior partner at Arnold Bloch Leibler. He co-chaired both the Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and the Referendum Council that culminated in the release of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Leibler is also national chairman of the Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council.

comments