An English novelist

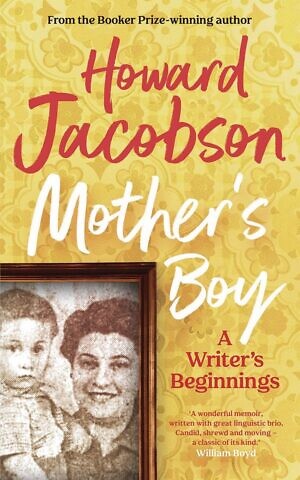

Booker Prize winner Howard Jacobson has released his latest novel, which he describes as a love letter to his parents. The AJN spoke to the author about discovering the writer within.

Howard Jacobson was constantly referred to as the English Philip Roth. While he says it’s a great compliment and hugely flattering, the comparison doesn’t describe what he does properly. Rather, Jacobson says he’s more like the Jewish Jane Austen.

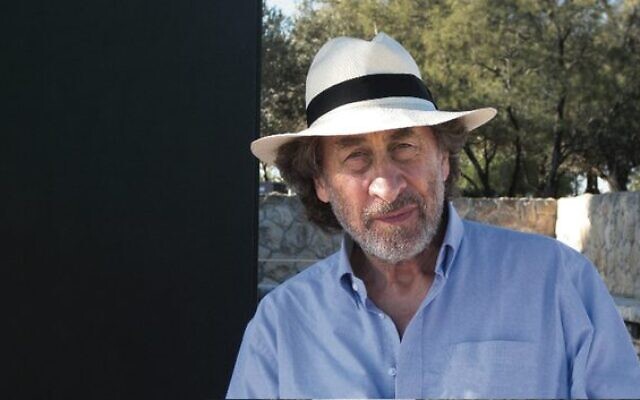

“The assumption was that I just leapt aboard the bandwagon of American fiction,” he told The AJN over Zoom, with rows and rows of books covering the wall-to-wall bookshelf behind him. While he said the great American novelists like Roth and Saul Bellow were authors he definitely came to admire, they were not his role models.

“I’m an English literature man. I was taught Dickens, Jane Austen, George Elliot. I hadn’t even heard of Philip Roth.”

So why the “Jewish Jane Austen”? Because of the way he writes. When describing the comparison, he said, “There was a kind of thing I did, a kind of way of writing prose, a love of a certain understated elegance… quite a stern moralism underneath everything that was less fluid and less wild, and maybe less exciting, than the Americans.

“The truth is, I was and am an English novelist.”

The author, who has just released his memoir, Mother’s Boy, explained that he’s not a great planner. When it comes to his writing, he starts and sees where it leads.

“I almost doodle on the page and something suddenly comes up, and then I follow that. It’s spontaneity. It’s also an inability to plan,” he laughed.

When talking about his favourite book, Kalooki Nights, he explained the book started almost the day after he had been at Shabbat dinner with a local rabbi. The book, which Jacobson refers to as “my best book … very Jewish book, very funny book, very angry book”, was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2006.

His Booker Prize win came four years later with The Finkler Question. It wasn’t the book anyone expected to win.

“It was longlisted, and I thought that’s fine, that will do, I can’t believe it,” he said, continuing to explain that he had to be convinced by his publisher to attend the function which would announce the shortlist. Six weeks later, his award was announced.

“You know what hope is like, even when you think something’s not going to happen, and indeed you know something is not going to happen. You still hope it might,” he said. As the chairman read the description of the winning book, Jacobson still didn’t cotton on.

“I heard him talking about this person called Finkler, and in the excitement, I thought, who is this bloody Finkler?”

Jacobson said the win was astonishing and a bigger prize than anyone knows. “What you don’t know, is that you’ll spend the next three hours that night facing the world’s press, like a leader of a country. There’s this barrage of questions,” he recalled.

Jacobson, whose first novel only came out in his forties, explained that Mother’s Boy is almost like a love note to his parents, and an exploration of why it took him so long to become the novelist he always wanted to be.

Jacobson, whose first novel only came out in his forties, explained that Mother’s Boy is almost like a love note to his parents, and an exploration of why it took him so long to become the novelist he always wanted to be.

“Part of the book is apologising to myself for that, and apologising to my parents for the fact that I led them to believe there was a book coming any minute, any second. And there was no book coming any minute for a long time.

“I’m trying to work out why it took me so long to do it,” he said, going on to explain that all he ever wanted was to be a writer. “I didn’t have footballers on my walls, I didn’t have pop groups on my walls, I had Dickens. I thought I would be Dickens,” he said.

As for his parents, he said he grew up in two very different worlds – his father as an entertainer, and his mother as an introvert.

“My mother encouraged me to read. She read poetry to me. It’s her voice that I associate with writing and with literature. When I was seven or eight, she – a totally uneducated woman – was reading me Tennyson and Matthew Arnold,” he recalled. “She gave me the literature bug.”

While his father never understood Jacobson’s fixation with collecting books, he influenced his desire to entertain.

“The part of me that’s my father’s son wants to write books that are entertaining. The part of me that’s my mother’s son is more reflective, more internalised. And that was the battle. It goes on now in my writing.”

As for the Jewishness of his books, he said as soon as he made his first hero Jewish, he had the voice, and he could suddenly find the words.

While none of his books focus on religiosity, they certainly touch on culture. “[It’s] Jewish thought, Jewish humour, Jewish intelligence, Jewish wit. I became a kind of exponent of it,” he explained. “I never thought about writing and Jewishness together before. I hadn’t read many Jewish writers. I was reading Jane Austen. And then it clicked. I could do it. I had the voice. It was Jewishness that got me going.

“Primarily when I’m writing, I want the book to feel alive. The kind of prose I write is spoken prose. I speak it in my head as I write,” he said. “It’s an obligation of language, first and foremost. The obligation to describe the feelings, embody the feelings, picture the feelings and in the most honest and honourable and surprising way.”

Howard Jacobson will be in conversation with Sarah Kanowski at Melbourne Jewish Book Week. For more and tickets, visit melbournejewishbookweek.com.au/event/howard-jacobson-in-conversation

comments