Art from Vienna’s golden era

THERE are some fascinating Jewish connections in the Vienna Art and Design exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), which highlights the works of Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Josef Hoffmann and Adolf Loos.

The exhibition has more than 250 works from the renaissance in Viennese art that started in the late 19th century and became known as the Secession period.

It is drawn from galleries and private collections in Europe, North America and Australia. The most prominent lenders are Vienna’s Belvedere and Wien museums and the exhibition is part of the “Winter Masterpieces” series, only on display in Melbourne from June 18.

The story of how many of these works survived World War II and came to be in Australia is explained by Tim Bonyhady, great-grandson of art collectors Moritz and Hermine Gallia, in a new book, Good Living Street: The Fortunes of my Viennese Family, to be published later this year by Allen and Unwin.

Perhaps it is not by accident that Bonyhady is an art historian and a curatorial adviser to the NGV on this exhibition.

“In November 1938 two sisters, one unmarried the other divorced, both unknown beyond the small circles in which they moved in Viennese society, fled Nazi Austria for Australia,” Bonyhady writes in the NGV’s 150th anniversary magazine.

The sisters were Hermine’s duaghters, Kathe, one of the first female graduates of the University of Vienna, and Gretl who was married to Viennese leather merchant Dr Paul Hershmann. The Hershmanns 16-year-old daughter Annelore accompanied them.

What is so extraordinary is that the sisters managed to bring with them the remarkable collection of art and design formed by their parents,who were among the leading cultural patrons of the time, and many of them will be on display in the Vienna Art and Design exhibition.

Luckily, their escape was before Kristallnacht, when portraits of Jews were considered worthless. So Klimt’s wonderful painting of Hermine was exempt from the punitive regulations preventing export of art treasures.

Like celebrated composer Gustav Mahler, who was closely involved with the rich artistic life of the time, the sisters had converted from Judaism to Catholicism to survive the Nazis.

Mahler, who was also conductor and director of the Vienna Opera, remarked that switching to Catholicism meant nothing more than changing your coat.

“Look,” he said to a friend, opening his lapels. “It’s the same person underneath!”

The renaissance in Viennese art began in 1897 when a group of artists, including Otto Wagner and his gifted students, Josef Hoffmann and Josef Olbrich, together with Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser and others, aspired to create a renaissance of the arts and crafts and to bring more abstract and pure form to the design of buildings and furniture, glass and metalwork.

They brought together under one umbrella artists who had practised as symbolists, naturalists, modernists and stylists and gave birth to a form of modernism in the visual arts, which they named Secession (Wiener Sezession).

This movement represented a protest of the younger generation against the traditional art of its forebears, a “separation” from the past towards a more adventurous future.

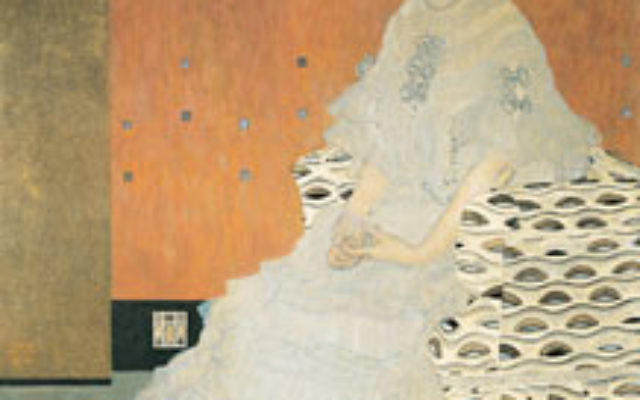

The first chairman was Klimt, whose 1904 portrait of Hermine Gallia forms a highlight of the NGV collection. It shows a thoughtful and mature woman in white, her head slightly cocked to one side as if she is contemplating the future with some well-deserved trepidation.

Less glittering than some of Klimt’s highly decorative portraits, it is nevertheless a masterpiece of quiet understatement and artistic innovation.

Consider alone the variety of materials the artist has managed to convey -– translucent lace, layers of chiffon edged with satin, a woolly ruff -– through which the soft pink flesh gently glows, all set against a patch of exotic, brightly coloured carpet to signal that this is a woman of taste and means, someone not to be trifled with.

Why, one asks, would the Gallia sisters have chosen Australia as a refuge instead of the United States at a time when there was so little cultural life? Simply because other members of the family were migrating to Australia.

When they settled in Sydney, they reunited all the disparate elements of the Hoffmann collection they had each inherited from their parents so that, as Bonyhady puts it, “for more than 30 years … there was no comparable apartment in New York, London, Zurich Budapest or Prague. Nor for that matter was there one in Vienna since most other Hoffmann interiors had been destroyed or dispersed”.

Although Gretl’s daughter Anne could have sold it after her mother’s death and made a fortune, she decided it should stay as a whole in Australia, the country that had saved them from death. So in 1976, the Hoffmann collection entered the museum largely intact.

Apart from the paintings by the masters of Viennese Modernism, Vienna: Art and Design features decorative objects and interior designs of Hoffmann and the Wiener Werkstatte (Vienna Workshop) that includes furniture, jewellery, silver and ceramic wares.

The Vienna: Art and Design exhibition will be at the National Gallery of Victoria, 180 St Kilda Road, Melbourne, from June 18 to October 9. Enquiries: ngv.vic.gov.au.

REPORT: Betty Caplan

PHOTO: Gustav Klimt’s Fritza Riedler (1906) in the Vienna Art and Design exhibition at the NGV.

comments