Hebrew’s new dawn

Ben Judah explores how a Moldavian Jew's pilgrimage in the 19th century foreshadowed the rebirth of the language of the Jewish people.

Was it guilt, boredom or longing? I’m not quite sure. All I can tell you is that in the pandemic I started seriously learning Hebrew.

Ani lomed. At lomedet. Anachnu lomdim.

At first the words could barely come out of my mouth. They got stuck on my tongue, or in the back of my throat, and made me stutter. Embarrassed by my sounds, I grew frustrated. My head felt like a sieve: whole verbs and endings kept slipping through it.

Ani kore. At koret. Anachnu korim.

Excuses started creeping in: that I was too old or too internet-brained to learn. That it didn’t matter anyway. And then I would hear it: there in the prayers; in a snatch of news. Both alien and familiar. And I’d feel a deeper frustration. Of being the one unable to ask.

Ani medaber. At medaberet. Anachnu medabrim.

And so I kept going. Slowly the words began to stick. The more I learned, as my sentences started to hold up, the more verses came out of the fog. Until, line by line, one paragraph at a time, then eventually page by page, I started to read.

Ani zocher. At zocheret. Anachnu zochrim.

I had not expected what I experienced next. With this little jump in Hebrew, Jewish and Israeli culture began to feel stranger and further away. I found myself reading more and more about Ivrit. Trying to pin it down. Until I became convinced that I didn’t understand this language – that the simple story I’d been told, of death and revival, was wrong. Until I felt I had never truly heard Israel before, in all its harsh complexity, and longed for the guides who could take me in.

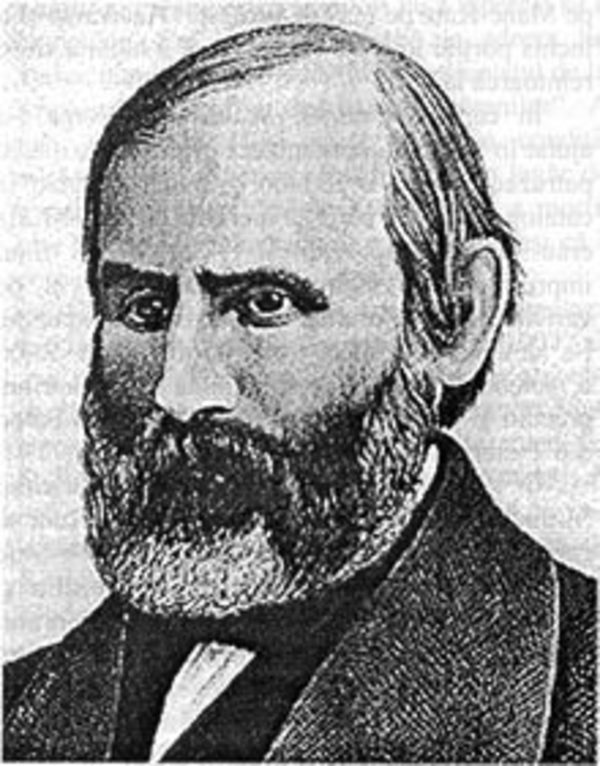

I was in this state when I found Israel Joseph Benjamin, at the New York Public Library, out of an almost random order up from the stacks. It was a worn copy and when I picked it up – Eight Years in Asia and Africa: From 1846 to 1855 – I had no idea what I’d found.

A few hours later I lifted my head in a daze. I’d found it: the guide I’d been looking for. Drawn in a bobbled kippah, his payot like ear muffs: a man who was the last medieval Jewish traveller and the first modern one. A Jew whose journey from Romania, through Iraq and India, all the way to China, caught the twilight of Hebrew as the language of rabbis and wanderers, and its dawning as a modern language. Through him and his journey, I first understood the Hebrew which never really died.

Abandoning his wife and five-year-old son, on January 5, 1845, Benjamin set out from Fălticeni, a small town with a Jewish majority in what was then the Romanian-speaking principality of Moldavia, west towards Austria. His mind full of the only things that his Jewish education and studies had armed him with: Talmud, Torah, Aramaic and Rabbinic Hebrew. Chalking off the principal towns of Austria “for personal matters” and then drifting for a year through Hungary, Serbia and what maps then called “Turkey in Europe”, the Ottoman province of Rumelia that still then made up most of the Balkans, he grew increasingly resolved to see the very edge of the Jewish world.

“There was a long and deeply cherished wish of my heart, a wish harboured from my earliest youth,” he wrote. “And I determined therefore to make first a journey to those parts, where once my forefathers dwelt in the days of their glory and of their misfortune, and thus, as in a vision, seek the traces of what remained of the ten tribes of Israel.”

He never returned home.

Styling himself as Benjamin II, the successor to Benjamin of Tudela, the 12th-century Sephardi traveller who had crossed the Mediterranean and the Middle East, this bankrupt Moldavian Jew made his way to Constantinople, preparing to visit the Land of Israel, Baghdad and beyond, courting and cataloguing the Jews he met along the way.

In a world where the first steamships were crossing the Atlantic, the first public railways were being laid and Friedrich Engels was about to publish The Condition of the Working Class in England, “Benjamin II” was convinced he might catch a glimpse of remnants of the tribes of Gad or Zebulun, somewhere in these lands out east being opened up by the colonial empires.

Both medieval dreamer, who captured how far the Yiddish-speaking masses had fallen behind the European bourgeoisie in the mid-19th century, and Victorian explorer, who foreshadowed the Yidden’s later journeys on modernity’s trains and steamships, to incredible and terrible new destinies, Benjamin II never found Manasseh and Naphtali. He travelled naively and wrote shakily and often badly. He compiled copious notes, his style full of biblical allusions and daydreams that, along with the manuscripts he collected, were often stolen by brigands on the Middle Eastern caravan trail. Nevertheless, he left us with a priceless document. A final account that captures how Hebrew was used internationally, as it had been for centuries, in the decades before modernity upended everything.

It was Hebrew that allowed him to discuss Talmud, showing off his Chabad erudition, with the Sephardi rabbis of Constantinople. It was Lashon Hakodesh that took him almost straight to Jerusalem, where he was frightened of thieves and pained by the destitution of the Jews. Hebrew took him into the homes and confidences of Jewish Damascus and Aleppo, where they spoke it “with a so-called Portuguese accent”. It allowed him to talk to the Jewish farmers and chiefs of high Kurdistan, who, to his horror, washed his feet as if he were a holy emissary raising money for the synagogues of Zion, only to pass the water around and drink it. And it was Hebrew, after crossing the deserts – then a great palm grove, where the rabbis once divined a language of date palms in their rustling – that allowed him to find his way to Baghdad, the city of Harun al-Rashid and One Thousand and One Nights “encircled by a glittering girdle, which is formed by the waters of the rapid and foaming Tigris”.

In this sense, the bumbling and impoverished visitor from Moldavia truly was Benjamin II – but he was also Benjamin the last. A generation later, across the Jewish world, that fluency in Hebrew, which Jewish elites had held on to for over 1600 years, was already fraying.

Fluency in writing, not in speaking. Because according to the Talmud, spoken Hebrew died out with Rabbi Judah HaNasi in 217 CE, and modern scholarship concurs. The language faded in the first and second centuries of the common era, with pockets in the Galilee surviving to the third.

What remained was a language to which all Jewish men, though few women, were exposed, but only a small number mastered: rabbis, scholars, sometimes merchants and travellers. This is the Hebrew that never really died.

It was Hebrew script that tied the rabbi, the merchant, the family, into the great web of faith and trade. And it opened doors, for this traveller, into places no Yiddish was spoken.

It is easy to imagine Benjamin in Baghdad, talking, haltingly, with the rabbi or the head of the family about how, as he noted, the trade with India was held entirely in Jewish hands, every few lines a familiar quote from scripture. The same way a Catholic priest would have spoken Latin on his travels, or an imam might have spoken Fusha Arabic. Theirs was not today’s phrasebook question-and-answer approach to foreign languages. It existed in a world where men committed far more sacred texts to memory and quoted them to communicate.

This Hebrew made Benjamin II – whose Talmudic imagination had him dreaming of the River Sambation, over which the lost tribes were said to live – the first Ashkenazi who recorded, in loving detail, the lives of the Sephardim and the Mizrahim. He noted their marriage customs, stories and superstitions, which were as much of a mystery to the Jews of Fălticeni as the ghost tribes of the Bible. A world that is truly lost.

Few people, in a single life, would ever hear as many of the Jewish languages as Benjamin II did: from Kurdish Jewish neo- Aramaic to Judeo-Amazigh, he experienced the Babel of the Jews. Most, like Yiddish, were variants of other languages, richly laced with Hebrew and Aramaic words. Most, like the Ladino he heard in ports around the Mediterranean, are now on their way to being extinct.

Back home, in Eastern Europe, between the shtibels, yeshivot and taverns, things were happening. Modernity was creeping in. This was especially true of the use of Hebrew. For decades two revolutions had been moving the Jewish world. The Haskalah, or Jewish enlightenment, was bringing new ideas, languages and ambitions into the shtetl. Older, but no less transformative, was Chasidism, a Jewish revivalism, with its ideal of the pious chasid. Both forces were present in the life of Benjamin II, who began as a Chabad chasid and then abruptly turned into his own kind of encyclopaedia-reading, French- and German-published maskil.

The books in the shtetl had changed. Chasidism had, over the last few generations, produced countless rough, living, Hebrew accounts of the lives of its tzaddikim, often splattered with Yiddish and ungrammatical. Modernity was hovering at the yeshivah door. The Haskalah, answering the cry of its own 18th-century heroes like Moses Mendelssohn, ushered new books in a variety of European languages, on all aspects of life, into every Jewish town. Reading was no longer primarily a religious activity.

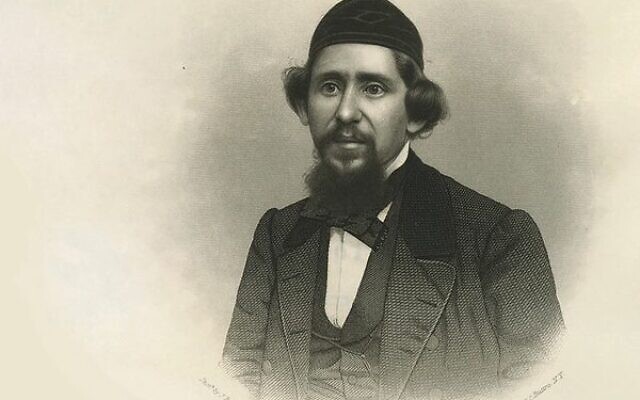

Benjamin II might have been dimly aware of Joseph Perl’s Revealer of Secrets, which is now identified as the first Hebrew novel, a coruscating attack on the Chabad movement, published in 1819. But it was little known and, by the 1850s, long since out of print. It is certain, however, that on his final return to Europe he would have become aware of the literary sensation in his absence: Ahavat Zion – The Love of Zion, by Avraham Mapu, which his contemporaries would have considered the first Hebrew novel. Published in 1853, this historical novel, written in copy-paste, faux-biblical prose, turned the landscape of the Bible into a literary world. It could soon be found everywhere: in yeshivot, in synagogues, in the studies of the rabbis reading it in secret by candlelight.

Benjamin II and Avraham Mapu had a lot in common. Educated by and faithful to the old system, but hungering for something more, they were the prototypical figures upon whom the modern Hebrew revival began: the last of the old world and the first of the new. Without fully understanding it, they were seeking to secularise their Judaism, which for them was lived through Hebrew, meaning such a process could only begin there. Patriotism and enthusiasm for the language, to quote Hillel Halkin, the great Israeli-American literary critic and historian of Hebrew, not only predated patriotism and enthusiasm for the land, it prefigured it. Within a year of Benjamin II’s landing in Europe, in 1855, the Mapu readers, the frustrated yeshivah bochurs and the eager maskilim would have a new form of reading material with the 1856 launch of Hamagid, the first newspaper in the language of the Torah. As they slowly secularised and modernised, a disparate generation began to write in the only language cheder had taught them to truly value – a language they could not leave behind. They feared that, if they did not try to save it, Hebrew might finally die.

This is an edited extract of Ben Judah’s “Ivrit: The language that makes a people” from the latest issue of The Jewish Quarterly: jewishquarterly.com

comments