High Holy Days on the battlefield

Rosh Hashanah, Kol Nidre and Yom Kippur were observed in the most challenging of circumstances by Jewish diggers serving in World War I and World War II.

World War I

While the circumstances of war – particularly the horrific, relentless and constantly threatening nature of trench warfare in Gallipoli and at the Western Front in France and Belgium – often meant that Jewish Diggers were not in a position to observe the High Holy Days, there are many examples of meaningful moments in which they did, in any form they could.

A striking example is in Mark Dapin’s landmark Jewish Anzacs book, published in 2017 by the Sydney Jewish Museum (SJM) and NewSouth Publishing, which has an excerpt from a letter written by Deniliquin-born, Sydney journalist Corporal Phillip Laurence Harris, in 1915 while serving in France with a unit called the Australian Ammunition Park.

While unable to observe Rosh Hashanah that year, Harris beautifully wrote of his touching experience to mark the eve of Yom Kippur.

“Although from the day we arrived in the field, cannonading was incessant,” Harris wrote. “On Kol Nidre, not a gun was fired. It was a brisk moonlit night, and the peaceful aspect of things was not disturbed. I sat with a friend, ‘listening to the silence’ till near midnight. Certainly no Kol Nidre service was ever half so impressive as this service of silence”.

Also stationed in France in 1917 at the 33rd Casualty Clearing Station on the Western Front was a nurse from Melbourne named Leah Rosenthal, who had joined the British Queen Alexandra Imperial Military Nursing Service.

Dapin’s book includes a letter she wrote to her family in St Kilda about a Yom Kippur service she attended, where she notes, “I was the only woman present”, as the rest of the nurses and patients had been moved to a safer location, with Rosenthal then revealing she felt the “honour in being maintained in that most dangerous spot”.

She even posted them the cap of a bomb that almost hit, and described how she had to wear a gas mask while crossing the hospital compound.

A year later, she was still serving in France, and once again was the only female attending a British military Yom Kippur service.

And in Gallipoli in September 1915, Sergeant Julius Neustadt reflected on recently arriving not long before Rosh Hashanah, in a letter to his parents, writing, “I tried to find out if there was a rabbi here – but do not think there is …

I believe the 19th [it was actually the 18th] is Yom Kippur, though I don’t think I will be justified in fasting on the food we get here. Still, I will try and make a little difference in that day.”

Neustadt was promoted to sergeant on Kol Nidre, and another Jewish Digger at Gallipoli, Major Eliazar Margolin, took temporary command of the 16th Battalion on Yom Kippur.

He also commanded its rear party during the evacuation in December, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

World War II

In Libya in the months prior to Jewish New Year in 1941, the small synagogue in Tobruk had been directly hit in a bombing raid targeting the city, causing so much structural damage that it was deemed unsafe and had to close.

A group of Jewish Australian and British troops based there were keen to hold a Rosh Hashanah service on September 22. So as Dapin notes in Jewish Anzacs – in the absence of a synagogue and a Jewish chaplain or rabbi – Major David Benjamin from Sydney took it upon himself to host one … in a concrete cave used by a British tank regiment, whose officer in charge had loaned it for a few hours.

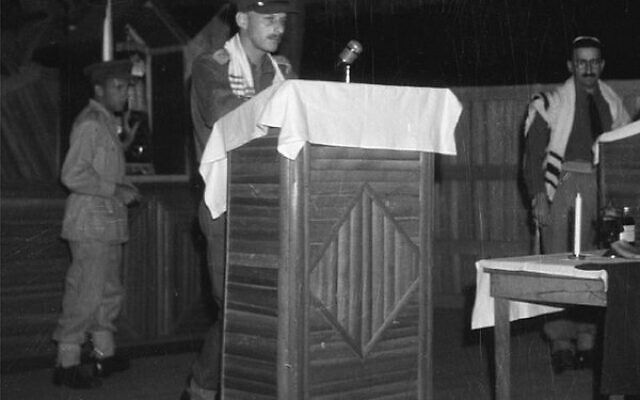

Photo: Sydney Jewish Museum

“I turned up at the concrete cave in fear and trembling,” Benjamin wrote in a letter to his family back home. “How was ‘my baby’ – our New Year Service – going to turn out. It turned out very well indeed – 31 men were there … The Hebrew part was read by Sergeant [Maurice] Sherwood, a Palestinian serving with the AIF … The English part was shared among four of us, Captain [Bob] Rose, Rupert [Michaelis], Colin [Pura] and myself.”

Gerald Pynt’s book, Jews in World War II, sheds more light on this unique service, via excerpts from a letter written by one of the attendees.

The letter reveals that the concrete cave once “had been used to house Mussolini’s ammunition … today it was our house of prayer”.

“There was no shofar, we had no talithim, our raiment was dirty and dusty, but we were a very happy gathering … several said to me how affected they were by the thought of Jews meeting in the middle of the desert to celebrate the New Year.”

Also on Rosh Hashanah that year, a little further east in Egypt, Melburnian Cecil David Super wrote a letter home about experiencing a service in Cairo, which is noted in Dapin’s book. He wrote: “In the crowded Jewish Club, there being about 350 to 400 Jewish soldiers gathered there from all corners of the British Empire. I noticed an Air Force officer … it was Rabbi [Israel] Brodie, formerly of Melbourne! He gave us a rousing sermon … full of fire and magnificent language. I have always been an admirer of his, but never in my wildest dreams did I expect to hear him preach in Cairo on Rosh Hashanah.”

Turning to the jungles of New Guinea, Reverend Louis Rubin-Zacks of Perth Hebrew Congregation, as Dapin notes, was based in the then Dutch territory’s capital of Port Moresby in 1943 to carry out his chaplaincy duties – work he described as including “a fair share of excitement, due to enemy bombing raids”.

He conducted services for Australian and American servicemen, attended by 500 soldiers on Rosh Hashanah, and 550 on Kol Nidre, including 20 to 30 Australians on both occasions. He wrote in a letter, “I have never yet experienced in civil life such a fine body of earnest and devout worshippers, following the services with such keen enthusiasm and attention. During the mornings, the continuous drone of planes overhead often drowned our voices, and the last few minutes of Kol Nidre were concluded in darkness, due to an air-raid warning. It was most impressive and profoundly stirring, under these conditions, in our chapel in a clearing in the jungle, to hear the men join heartily in singing Yigdal and Olam, and finally to disperse to the age-old tune of Hatikvah.”

When Rubin-Zacks returned to Australia in 1944 due to ill health, Chaplain Rabbi Lazarus Goldman from Melbourne – who had already served in Egypt, Libya and Syria – replaced him in New Guinea, and also visited troops in Indonesia, Borneo and the Solomon Islands. During Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur in 1944, Goldman, ably assisted by Captain John Einfeld, led services in a straw hut in Lae that was crammed with 350 Australian and American servicemen and women.

The SJM’s military history collection includes photos of those services, and also a photo of Digger Albert Abraham Hertzberg blowing a shofar at a 1944 Rosh Hashanah service in an undisclosed location in that region, and also a letter written to his parents by attendee Hy Havers, a US air force captain, who was mightily impressed.

Havers wrote, “You have every right to be proud of Albert, and let me tell you that he is a humdinger of a shofar player … I wish you could have seen the eyes and faces of all the men attending, there was joy on hearing the old shofar call.”

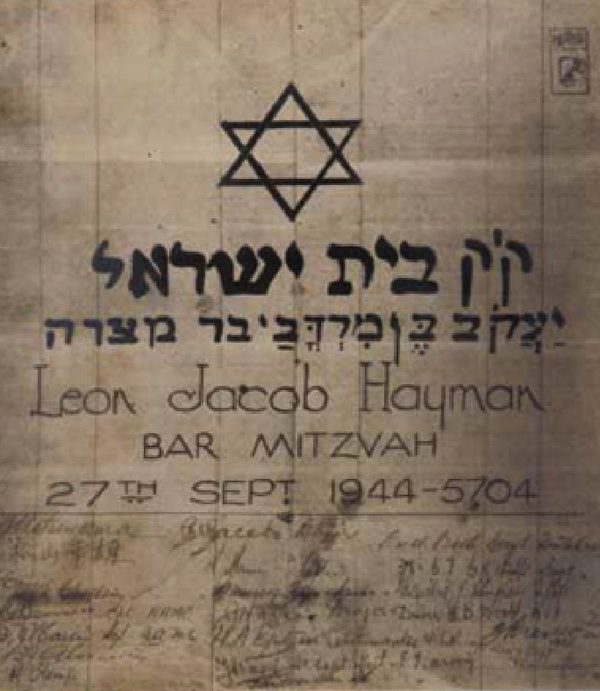

At the Tamarkan POW camp in Thailand in 1944, a bar mitzvah ceremony was held in the most unusual of circumstances. It is well-documented in Pynt’s and Dapin’s books and other sources, but it was only just discovered – by Sydney-based Operation Jacob co-ordinator Peter Allen in the process of assisting with research for this article – that the date of the ceremony, September 27, was actually Yom Kippur.

Saddened by not being able to be in Melbourne to attend his son Leon’s bar mitzvah, Victorian signaller Mark Hayman was determined to hold a service by proxy.

The Japanese were suspicious of that request, but eventually granted his wish on the condition a Japanese interpreter be present.

About 60 Australian, British, Canadian and Dutch POWs took part, even signing a bar mitzvah certificate for Leon, which today is held by the Australian Jewish Historical Society (Victoria).

According to Pynt, the Japanese interpreter expressed his best wishes for Leon, and hoped he and his father would reunite soon – which they did.

Pynt noted that because the service was to be followed by a social gathering, the date chosen was not a sabbath.

Allen said, “It would seem that the Jewish POWs at Tamarkan had no way to confirm the date of Jewish festivals, so were not aware that they were actually celebrating the bar mitzvah on Yom Kippur!”

Interestingly, signalman Neville Milston of Sydney had loaned his Singer Daily Prayer Book to Hayman for use in the service.

A year later, while temporarily stationed at an ex-POW camp near Bangkok after the Japanese surrender, Milston took part in a “short, but moving and emotional” outdoor Rosh Hashanah service attended by 12 to 15 colleagues, and his Singer siddur was put to good use once more.

Milston, who died in 2007, first used that siddur at his bar mitzvah at The Great Synagogue in 1933 and it stayed intact throughout his time in POW camps in Malaya, Burma and Thailand.

Keeping the faith

Maintaining religious traditions and celebrating Jewish festivals was, and still is, very important to many Jewish Diggers on active service, but obstacles and logistical challenges made that difficult.

The role of Jewish chaplains – from the first Australian Army chaplain, Rabbi Jacob Danglow [whose career spanned 54 years], and the the first to serve overseas, Rabbi David Freedman – to Lieutenant Harold Boas who was appointed as a Jewish liaison officer by the Australian YMCA in World War I, was vital in making religious observance more accessible to the troops.

Having access to Jewish literature was seen as important, and the first prayer book specifically published for Jewish soldiers in Britain and Australia was the ‘Khaki’ Prayer Book, of which the SJM has an original that was first taken to battle in World War I by Oswald Benjamin, and then used by his son David Benjamin in World War II.

In 1943, on Rabbi Danglow’s urging, the Jewish Chaplains of Australia decided to print an Australian Service Prayer Book, a Haggadah and later a Prayer Book for the Solemn Days. The SJM’s collection includes the latter in original form, printed in 1945, and donated by Enid Himmelhoch.

These books were in part supplied by the Jewish Veterans’ Associations – a tradition which continues to this day – and chaplains often inscribed them with a personal message.

Deadly statistics

According to Peter Allen, five Jewish Diggers lost their lives on Yom Kippur in World War I.

Second Lieutenant Keneth Solomon died of his wounds on September 18, 1915 at a UK hospital after suffering them in a battle at Suvla Bay in Gallipoli on August 22.

Four men – Lieutenant Wilfred Norman Beaver, and Privates Alexander Cohen, Joseph Cohen and Abraham Jacks – were killed in action on September 26, 1917 in the Battle of Polygon Wood in Belgium.

While no Diggers were killed on Rosh Hashanah in either of the two World Wars, 10 soldiers died in the Great War, and three died in World War II, in between erev Rosh Hashanah and Kol Nidre.

The AJN would like to thank Roslyn Sugarman from the Sydney Jewish Museum, and Peter Allen who is conducting further research on behalf of the ACT Jewish Community and the Australian Jewish Historical Association into the lives and service records of all Diggers named on the Australian Jewish War Memorial in Canberra, for their assistance with this article.

comments