How an Olympian is driven by her nana’s strength

'I’m sharing this tonight for the first time – I’ve told this story socially to family and friends, but never in such a formal setting'

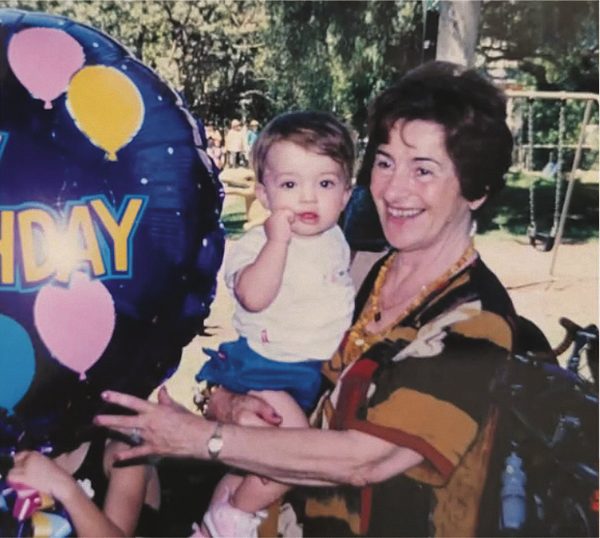

IN a special March of the Living Australia webinar, race walker Jemima Montag described how the passing of her nana, Judith, one month before her sixth-place finish in last year’s Tokyo Olympics – and uncovering Judith’s Holocaust survival story through her handwritten letters – changed her approach to both sport and life through values-based motivation.

“I’m sharing this tonight for the first time – I’ve told this story socially to family and friends, but never in such a formal setting,” Montag said.

Born Judyta Joachimsmann in the town of Wieliczka, Poland, her nana’s childhood was thrown upside down when Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939.

In the first letter in the family’s collection, her nana wrote that her “first sad memories are evoked in the year 1940, the deportation from Krakow, [then] a two-year farm stay with my grandparents on a farm [safe house] near Gorlice … and the loss of my mother on the 14th anniversary of my birth”.

On August 29, 1940, Judith’s mum, Victoria – being a few years older than her husband, Roman – was presumably taken by the Nazis to a death camp.

The family had been herded by Nazi officials into two groups, and in what proved to be her heroic final act, Victoria urged Roman to join the group of Jews being selected for work, and insist that he was five years younger than his real age of 47.

It worked, and Roman – who was later on Schindler’s List – and his children Judith and Ruth, were sent to a Nazi camp near Krakow to work at a nearby factory.

There, Judith was tasked with checking manufactured cables to be used by the Nazis, so she often, courageously, declared faulty cables as being in good working order.

As Montag explained, “It was a fine balance between playing by the rules, and taking clever risks.”

On Judith’s 16th birthday, on August 16, 1944, she and Ruth were forced onto a train to Auschwitz concentration camp, and for almost the next two years, Judith was known as number 26293.

Montag explained how Judith demonstrated incredible stoicism, and how Ruth’s boundless optimism amid the horrors faced every day, gave her the comfort and strength to continue.

Surviving a death march from Auschwitz in January 1945, the sisters were locked in a women’s camp on the final day of the war in May 1945, when Ruth was shot in the leg.

Ruth survived that, only to be murdered a year later in Poland by a group of antisemitic teenage boys, prompting Judith and her father to move to Paris, before Judith migrated to Australia in 1954 – on a ship’s fare paid by Jewish Care – to be with her future second husband, Richard.

Montag said she draws “so many lessons” from her nana’s story of survival, including her stoicism, her strong work ethic, and how she found strength in her family unit.

But the biggest one is being able to “put everything in perspective”.

“Life has its challenges – there are going to be ups and downs … but we’re lucky to have the opportunity to be here, living, and it’s because of the strength, persistence, and sacrifice of that generation of survivors that we have this opportunity,” Montag said.

She also reflected upon the strength she gained by wearing a special bracelet in her race at the Tokyo Olympics, and since then when racing and training.

Back in 2019, when her nana was in her late 80s, one of her necklaces was cut into three bracelets – one each for Jemima, and her sisters Piper and Andie.

“It was my auntie Vicki’s idea, and Vicki has joined tonight’s Zoom,” Montag said.

“When I see it glistening in the sun, and when I feel it physically moving up and down my wrist when I’m racing, it’s a reminder to think about our story, and the strength that’s in me, and gratitude for the opportunity to be here, doing what I’m doing.”

comments