How the tribe has influenced the genre

“If you want to talk about a singular Jewish contribution to hip-hop, it’d be Rick,” said Dan Charnas, a journalist and arts professor at NYU. “Instead of hip-hop being rapping over disco instrumentals, he conceived of it as sonic collage art.”

(JTA) – Like many parents, Mickey and Linda Rubin indulged their only child Ricky’s various hobbies. Ultimately, they hoped he would set his artistic interests aside and choose the sensible career of an attorney.

Ricky famously stuck with music.

In 1983, when he was at New York University (NYU), he borrowed $5000 from his parents to record a song by a local rapper, T La Rock and release it on his new label, Def Jam. The song, It’s Yours, was a hit and caught the attention of businessman Russell Simmons. The two joined forces and turned Def Jam into a hit factory. As a producer, Rick Rubin would go on to work with some of the most celebrated rappers of all time, including LL Cool J, Run-DMC and Public Enemy.

“When I started Def Jam,” Rubin told The New York Times Magazine in 2007, “I was the only white guy in the hip-hop world.”

He certainly was not, but he was one of the only white Jews making rap records until Michael ‘Mike D’ Diamond, Adam ‘MCA’ Yauch and Adam ‘Ad-Rock’ Horovitz – better known as the Beastie Boys – burst onto the scene. Rubin produced and released the group’s 1986 debut album, Licensed to Ill, which became the first rap album to reach No. 1 on the Billboard 200 chart.

“If you want to talk about a singular Jewish contribution to hip-hop, it’d be Rick,” said Dan Charnas, a journalist and arts professor at NYU. “Instead of hip-hop being rapping over disco instrumentals, he conceived of it as sonic collage art.”

Fifty years ago, on August 11, 1973, hip-hop was born (or so the origin story goes) when Jamaican Americans Cindy Campbell and her brother, a DJ who went by Kool Herc, hosted a back-to-school dance party in the recreation room of their Bronx apartment building.

Fast-forward to 2023 and hip-hop is ubiquitous – not just on Spotify and TikTok, but across pop culture, from television to fashion.

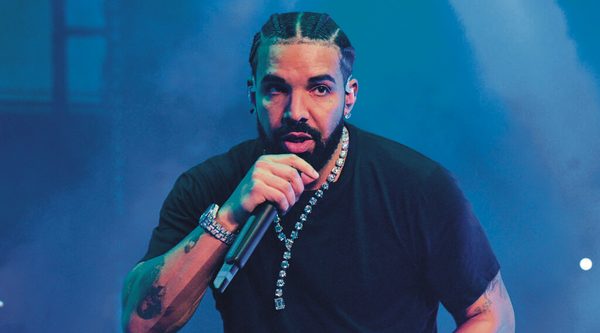

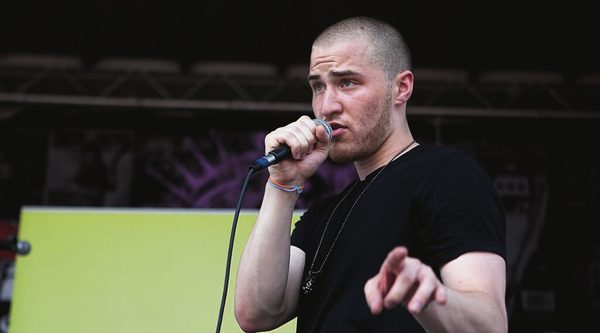

Over the last five decades, many Jewish rappers from different backgrounds and nationalities have left their mark on hip-hop culture, from Drake to Doja Cat, Mac Miller and Nissim Black, to name just a few. In the early 2000s, religiously observant artists such as Y-Love and Matisyahu carved out a niche for rap infused with Jewish wisdom and spirituality. Today, there are several rappers who make Judaism a prominent part of their stage personas, from Kosha Dillz to Lil Dicky to BLP Kosher. There is also a vibrant, multilingual hip-hop scene in Israel.

But the biggest contributions that Jews have made collectively to hip-hop may be on the business side, as managers and record label executives. “White people have played more of a role on the business side than as artists because hip-hop is, for the most part, a Black art form,” explained Charnas.

In his 2010 book The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop, Charnas shares the stories of the record label executives who commercialised hip-hop, including several Jewish ones: Roy and Jules Rifkind, owners of the label that released one of the first rap records in 1979, King Tim III (Personality Jock) by Fatback Band; Aaron Fuchs, founder of Tuff City Records; Tom Silverman, founder of Tommy Boy Records, whose roster of musicians included Queen Latifah, Coolio, De La Soul and Naughty By Nature; Jerry Heller, co-founder of Ruthless Records with rapper Eazy-E; and Julie Greenwald, Def Jam’s head of marketing in the ’90s (who now runs the Atlantic Music Group).

“I … decided to run a record company on the belief that this Black music, like every other Black music in history, would be worth codifying,” Fuchs said. He later mentored Rubin and even produced some songs himself using the pseudonym Oliver Shalom, a play on the Hebrew honorific for the dead, alav ha-shalom (peace be upon him). “I knew it would last, but I didn’t know that it would revolutionise music the world over,” he said.

In response to a direct message on Twitter, Chuck D of Public Enemy shared the names of the Jews he believes have made the biggest impact in hip-hop, in addition to Rubin: the Beastie Boys; MC Serch of interracial rap group 3rd Bass; Lyor Cohen, who started as Run-DMC’s road manager and went on to run Def Jam after Rubin’s departure; and Bill Adler, Def Jam’s onetime director of publicity who helped Public Enemy weather an antisemitism controversy in 1989.

Chuck D described the 1980s rap scene as a “melting pot of personality, ego, pioneering, money, race and everything else”.

Beyond the boardroom, Jews have also played a significant role in hip-hop as talent managers. Among the best-known are Heller (N.W.A.), Paul Rosenberg (Eminem, as well as Jewish rappers Action Bronson and The Alchemist), Leila Steinberg (Tupac Shakur, Earl Sweatshirt) and Todd Moscowitz (Gucci Mane).

Managers both inside and outside of hip-hop have long been vilified for profiting off their artists’ creativity and labour. Steinberg’s story is different: she accepted very little money while working as Shakur’s first manager because she did not want to be perceived as a white person taking undue credit for a Black person’s achievements.

“Back then, I really wanted to participate [in hip-hop] as an activist and couldn’t make sense of this being about money and business,” she said in an interview with JTA earlier this year. “I’ve reshaped a lot of my thinking – if you’re not making money, you can’t make change in the world.”

Many of the culture’s most enthusiastic chroniclers are Jewish: Jonathan Shecter and Dave Mays, who co-founded the ground-breaking hip-hop magazine The Source; DJ Vlad (born Vladimir Lyubovny), whose YouTube channel features interviews with numerous rappers and has 5.5 million subscribers; Nardwuar (John Ruskin), a Canadian journalist whose unpredictable interviews with rappers receive millions of views on YouTube; and ItsTheReal (Eric and Jeff Rosenthal), who recently released a podcast about the heyday of rap blogs. And then there’s Charnas himself, who was one of the first writers at The Source and a founder of hip-hop journalism.

Charnas connects Jewish involvement in so many different aspects of hip-hop to the historical alliance between Jews and Black people, saying there are “cultural affinities”.

He added there has never been a “Jewish cabal” running the show, a charge that a small number of big-name rappers – including most recently Ye, formerly known as Kanye West – have made. In 2008, Jay-Z and Russell Simmons recorded a PSA about antisemitism geared toward hip-hop artists and fans that was produced by Rabbi Marc Schneier’s Foundation for Ethnic Understanding. Since then, Ice Cube, Nick Cannon, Jay Electronica and, yes, even Jay-Z have all found themselves at the centre of antisemitism controversies.

Y-Love, the trailblazing Black and Jewish rapper who is known for rhyming in Hebrew and Aramaic, said the rappers who have been accused of antisemitism are not saying anything original.

“It’s the same antisemitism,” he said. The best response to the hate, he said, is for Black Jewish rappers with huge fan bases such as Drake and Doja Cat to stand up and say publicly: “When you talk about Jews, you’re talking about me.”

One of the positive legacies of hip-hop, he noted, is that it has allowed Black Jewish rappers like himself to get on stages and screens and show the world just how diverse Jews are. “I think that through embracing hip-hop, the Jewish community added a lot to its own continuity,” he said.

comments