On train trips in Nazi-occupied France, three-year-old Michèle Kneppel was too young to understand the peril she and her mother faced.

The infant could not know her mother Ruth was a courageous agent of the maquis, the collective of French rural guerilla movements, which took its name from the maquis or scrubland which they frequented, resisting the German occupation.

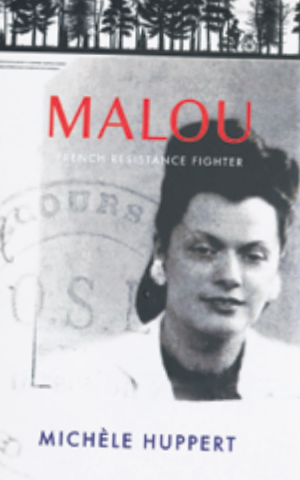

On joining the Maquis, Ruth had adopted the nom de guerre of Malou, and had traded her obligatory yellow Star of David for an Algerian Christian identity. An Italian passport issued to her by the Maquis gave her cover, and importantly, allowed her and her young daughter to travel the trains undetected.

As an agent de liaison for the Maquis, Malou would be the only name by which Ruth was known to the Maquisards, who never disclosed their real names to one another, or exactly where they came from.

To the other passengers on these train trips, Ruth and Michèle were an unremarkable mother and child. But Ruth was listening for snatches of conversation, or other clues – vital shreds of information that could be assembled to help the French Resistance.

“From a very early age, I was taught behavioural codes,” Michèle Huppert, as she is today, tells The AJN, when we speak at length about her newly launched biography, Malou, French Resistance Fighter.

“She showed me how to behave, so to speak,” Huppert says of her mother. “I could look at her, at her eyes, and with a little flicker or a smile, I knew to speak or not speak. That’s how we did it for five years.”

The intensity between mother and daughter, punctuated by these non-verbal cues, was an incredible bond which kept them spiritually at one, even when they were physically apart at times when Ruth had to take on far more dangerous work.

Every time she left me, she must have thought maybe that’s the end, I won’t see her again. But I didn’t know, I didn’t feel it at the time. That’s how well she protected me with her friends.

For many of these assignments, she would leave young Michèle with other members of the Maquis in Villeneuve sur Lot in France’s south. As most of the Italian Maquisards had left their families behind in Italy, she was virtually the only child in the group.

As Malou, Ruth would ride a bicycle on her clandestine errands, a revolver hidden in her bag. Well dressed, multilingual and coolly confident, she helped gather information to aid efforts to smuggle weapons to Resistance assassins, to bring coded messages to fighters in the scrublands, and to break Maquisards out of prison.

Her mother “made sure that wherever I was, I would be contented,” explains Huppert. “I was very nicely looked after but I must have missed her. She always made sure I was safe and that I understood she would be back for me, although some of the trips she made were harrowing.

“Every time she left me, she must have thought maybe that’s the end, I won’t see her again. But I didn’t know, I didn’t feel it at the time. That’s how well she protected me with her friends.”

One time, rounds of gunfire were heard at the notorious D’Eysses prison at Villeneuve sur Lot, where many Jewish prisoners were known to be held, and Ruth and other Maquisards prepared themselves to hide escapees. But chillingly, none were seen to emerge after the shootings.

A particular mission was personal for Ruth. Discovering that her husband had been arrested by the French police, she went to rescue Fred, who had been imprisoned in Lyon for six months.

Shortly after arriving in Lyon, Ruth was also arrested and was interrogated for six hours. She admitted being Jewish. Yet to her surprise, the chief of police turned out to be a Resistance operative and released her along with Fred.

In what seemed like another world, in 1933, the Kneppels had moved from their home in Vienna to Paris. Adolf Hitler had taken power in Germany, but in Paris, studying French at the Sorbonne, life had been peaceful and exciting for Ruth.

She was pregnant with Michèle in 1939 when World War II broke out, and as the German army closed in on Paris in 1940, her parents hid with her in various homes.

When the danger of being arrested by the Nazis became too dire, the family fled Paris and later migrated to the free French zone in the south, carrying Michèle, then a few months old, in a shopping basket.

At the border between occupied France and the free zone – later co-occupied by the Germans and Italians – the family separated. Fred and his mother set out for Nice, while Ruth and Michèle made their way to the Dordogne, where she knew friends who could hide them.

“We separated at the border because we felt a larger group like that was harder to manage,” says Huppert.

Ruth had first encountered the Maquis on a farm where she and her infant daughter were hiding. Her mother was introduced to the Resistance by an Italian Maquisard, a refugee of the Benito Mussolini regime, as many in the movement had been.

Ruth’s parents Leo and Margaret Altmann had been among Austrian Jews deported to Riga in Latvia. During their journey, the prisoners were forced from the train by the Nazis and shot to death. Ruth joined the Maquis because “she wanted to avenge them”, says Huppert.

“The Resistance were small groups that could set themselves up where the army couldn’t, and this is where they could do their work,” Huppert explains.

In the lead-up to D-Day in 1944, the Resistance, under the direction of General Charles de Gaulle from his exile in London, ramped up their sabotage operations on the German army as it moved north towards the Allied landing points at Normandy.

Michèle and Ruth were liberated in the south shortly before the Allies reached Paris. “After the war, I remember the joy,” says Huppert. “The French collaborators were put on trucks and driven through the cities.”

At the time Paris was liberated, Ruth had become the head of the Maquis at Villeneuve sur Lot and stayed on to document its many activities. After some weeks, says Michèle, “she cleared out her desk and took her daughter home to Paris”.

A brief visit back to postwar Vienna was depressing and the family encountered cold contempt for surviving Jews, says Huppert. Conversing in French, her mother overheard a group of Viennese engaging in antisemitic banter. “They thought she didn’t understand German … they spoke trash between one another. But my mother broke into German and gave them a piece of her mind.”

In Paris, Ruth helped orphaned Jewish children through the humanitarian organisation OSE (Oeuvre de Secours des Enfants).

After the war, I remember the joy…

At OSE, Ruth had told her supervisor she had a second cousin who had emigrated to Australia in 1938 and was living in Melbourne. Her boss suggested Ruth should place a notice in a Jewish newspaper in Australia. The notice in The Australian Jewish News worked, and they located the cousin, Paul Stein.

Fred remained behind in Paris, but Stein made arrangements for Ruth – and Michèle, now 12 – to settle in Australia in 1952. After an amicable divorce from Fred, Ruth later married Paul.

Completing school and business college, Huppert married Czech-born Holocaust survivor Paul Huppert, a scientist and electronic engineer, and she made a career in business and in the fashion industry.

After Ruth passed away in 2007, Michèle began to patch together her shreds of memory lingering from the war years. “I had never asked questions of her. I was always very discreet. That’s how I was brought up, ‘Don’t ask questions.'”

But combing through her mother’s documents, “certain things, especially when I looked at photos, they came back to me. With the help of books I’ve read in France about that period, I slowly, slowly – like a jigsaw puzzle – discovered the life that we led.”

She was inspired in her search by Les Parisiennes, a book by journalist Anne Sebba, which detailed courageous Parisian women in World War II, and by the findings of historian Danielle Daquis.

Michèle visited France, where she toured the Centre National Jean Moulin, a Resistance museum near Bordeaux, and donated copies of documents she had found among Ruth’s possessions. Michèle has also donated a trove of memorabilia about the French Resistance to Melbourne’s Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC).

In an online event at JHC last month, she explained her mother’s story, as told in Malou, French Resistance Fighter, to Dr Anna Hirsh, JHC’s manager of Collections and Research; the gripping story of a mother and daughter in the darkest of times. Segments from Ruth’s video testimony to the JHC in 2001 were featured. Michèle’s granddaughter Genevieve Huppert read an extract from the book, and Anti-Defamation Commission chair Dvir Abramovich paid tribute to Ruth.

In an online event at JHC last month, she explained her mother’s story, as told in Malou, French Resistance Fighter, to Dr Anna Hirsh, JHC’s manager of Collections and Research; the gripping story of a mother and daughter in the darkest of times. Segments from Ruth’s video testimony to the JHC in 2001 were featured. Michèle’s granddaughter Genevieve Huppert read an extract from the book, and Anti-Defamation Commission chair Dvir Abramovich paid tribute to Ruth.

Huppert, now a great-grandmother, told The AJN that, aside from her historic research, her book sums up “what I felt in my heart”.

comments