Sketching a life

FROM hundreds of stories around the globe, Olga Horak’s was consistently chosen – time and time again.

After filmmakers Adam Dostalek and Ben Saravia interviewed a range of elderly people from countries including Australia, Argentina, China, Kenya and Qatar – one of whom was Olga – five of these stories were then developed into proof-of-concept animations.

When executive producers at an Argentinian animation festival voiced interest in seeing a single episode centred around one figure, they unanimously selected Olga – a 94-year-old Holocaust survivor, and pillar of strength in the Sydney community, whose attitude towards life can, quite simply, be surmised as “phenomenal”.

“The way she articulates her message to the next generation, to humanity, affects us all. It doesn’t matter what you are – no matter if you are white, black, Jewish, Muslim … We want everyone to be able to appreciate her story,” reflects Dostalek.

“You look at someone like Olga, and her attitude towards life is phenomenal.

“When it comes to talking about wisdom and vision, she has messages that will resonate with the world.”

Dostalek and Saravia are now developing a poignant animation short tracing Horak’s life, and her ever-expanding appreciation for the beauty around her.

“The catalyst for the animation was coronavirus but the subtext and the depth has come from what this woman has survived,” says Dostalek.

“There is a global mood of change, and this Holocaust survivor who has literally endured hell on earth will share her wisdom.”

Extending her gratitude to the filmmakers, and after viewing a small segment of the animation in its development phase, Horak remarked, “I have never seen an animation in connection with subjects like this. Topics like this are usually in books … but this was really a total surprise, but a nice surprise. It is an idea that is completely different.”

Optimistic that the final product will reach a wide array of people, she commented, “Producing something new always creates interest, and interest to groups who have never been introduced to Holocaust stories before.”

According to Horak, “For anyone who has experienced hardship or disappointment, you cannot live with all that sadness, you always have to hope for something better.”

One of her mantras – “Crises come and crises go, but after rain comes sunshine” – acts as a guiding light to a better life.

Born in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia in 1926, Horak was 14 when the war broke out in 1939.

In 1942, her sister was rounded up and taken to Auschwitz. Horak and her parents went into hiding, but were betrayed and also sent to Auschwitz where her father and grandmother immediately perished in the gas chambers.

She and her mother endured the camps together and were liberated on April 15, 1945. But tragically, her mother passed away the following day.

“I had nobody after the war,” she remembers, but she did have hope.

“That is why I say, ‘after rain comes sunshine’.

“For most of the survivors, there were times when we had trouble in our lives, but we also had pleasure and happiness and we created new families.”

In 1947 she married John and they have two children.

“To me, this was happiness; to have a family again.”

Growing a generation of upstanders

ZOLTAN Gervay was an amazing man.

He was interesting and a voracious reader, though he never thought he was smart, remembers his daughter Susanne.

He knew hardship and suffering intimately, having endured gruelling winters and forced labour in one of the most remote parts of Siberia, before making a quick and successful escape to Budapest.

On the rare occasions that Zoltan spoke about the Holocaust, he revisited the traumas of his past in the trusting company of his adoring daughter.

“I must’ve been about eight,” recalls Susanne Gervay, now an Australian author of children’s and young adult literature.

“He said to me, ‘In the war, there were houses with children.’ He said he would go at night to give food and help, and he said that one night he went to one of the houses and it was empty.

“He knew the children had been taken away … He said it just once, and then he didn’t speak about it again.”

From that moment, Zoltan’s disturbing recollection remained imprinted in Susanne’s mind. Only decades later did she learn that the mysterious house Zoltan had mentioned was Budapest’s Glass House – a safe refuge for Jews escaping deportation to Auschwitz – inspiring the premise of Susanne’s latest book, Heroes of the Secret Underground.

In her part-autobiographical and time-slip novel, released to coincide with Yom Hashoah on April 7, 12-year-old Louie uncovers a curious rose gold locket and is sent down a trail of discovery and transported to Budapest 1944.

“Stories are one of the most effective ways to open discussions between parents and young people. Because they will read this book and then they will ask, ‘But why did that happen? How? When?’” says Susanne.

“Young people are searching for meaning and if they love a book, they will read it 10 times. They will be able to quote segments because they are absorbing it into their value system.”

In writing Heroes of the Secret Underground for ages 9+, Susanne seizes the opportunity to instil in readers a strong moral compass.

“They are at the cusp of: who is God, why am I on this earth, why is there racism, what is happening, where am I going, how can I help?” Susanne fires, adding how young people are also at “the cusp of despair”.

“Young people often don’t have much experience and they believe when they face a real challenge it is the end … It’s not. It’s the process of learning and meeting [a challenge] and becoming resilient.”

Adds Susanne, “Not everyone will become a great warrior or advocate or champion for justice, but if enough young people see it through story, they at least won’t be part of the herd … That is extremely important. They will know it is not right.”

On her own journey of self-reflection, Susanne confronted her experience growing up as the daughter of two Holocaust survivors through the creative writing process.

“It was a really painful book to write, even though it is ultimately celebratory,” says Susanne.

“It makes me cry [as] it’s so close to my parents’ experience. I hope – and this is where I have fear – that I have done them justice.”

Heroes of the Secret Underground is published by HarperCollins. Purchase a copy of the book at bit.ly/3chsAcC.

A window into the past

ESTABLISHED in 2016, the David Labkovski Project (DLP) uses over 400 pieces of art created by its namesake as a tool to educate about the Shoah and bring history to life.

“We realised that the uniqueness of our educational approach centred around the universal language of art and the ability of this body of artwork to reach and engage audiences from all backgrounds,” says founder and executive director Leora Raikin, Labkovski’s great-niece.

“Our project-based curriculum transfers ownership and responsibility onto students so that they can become curators, docents and educators to their peers and community.”

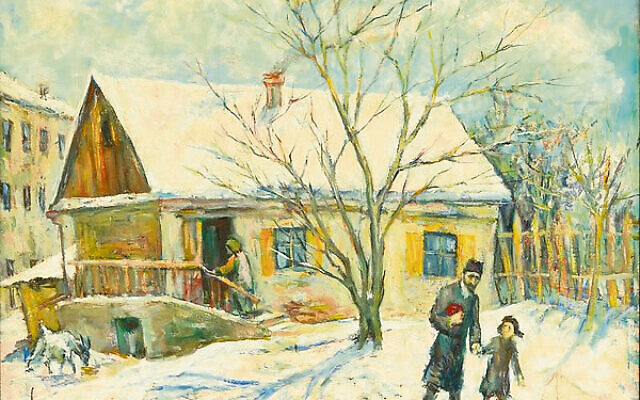

David Labkovski grew up in Vilna, a thriving city for Jewish culture prior to the second world war that was dubbed “the Jerusalem of Lithuania”.

His art from the era depicts a city where Jews comprised nearly fifty per cent of the population, with numerous synagogues, Jewish schools, newspapers and cultural organisations.

“Labkovski tells the story of a community that existed before the Holocaust, giving the viewer a remarkable glimpse into the Jewish community of his childhood and and the history of his community,” Raikin says.

After being drafted into the Red Army and also spending three years in a Siberian Gulag, he returned to a destroyed city.

After being drafted into the Red Army and also spending three years in a Siberian Gulag, he returned to a destroyed city.

His self-portraits from the time show his despair in the prison camp, while a painting of Raikin’s great-grandparents, their daughter and twin grandsons being forced out of their home by the Nazis and into the Vilna ghetto – which hung for years in her grandparents’ living room – had a lasting effect on Raikin.

“It was this painting, along with hearing and listening to my grandfather’s stories about life growing up in Vilna, that created a a desire in me to learn, read, study and immerse myself in anything related to the Holocaust,” she says.

“In his later years, David began painting flowers, fruit and landscapes, representing his peace of mind, spiritual renewal and sense of hope for the future.”

Marrying the past with the future, DLP has also created a virtual reality component that transforms Labkovski’s art into an immersive experience.

Marrying the past with the future, DLP has also created a virtual reality component that transforms Labkovski’s art into an immersive experience.

“This VR experience uses cutting edge technology to immerse students in the paintings,” Raikin says.

“[It] provides participants an opportunity to explore the ‘world that was’ by stepping into Labkovski’s artwork, interacting with objects in a pre-war home, hearing about the lives of the characters in the paintings and exploring the shulhof – synagogue courtyard.”

comments