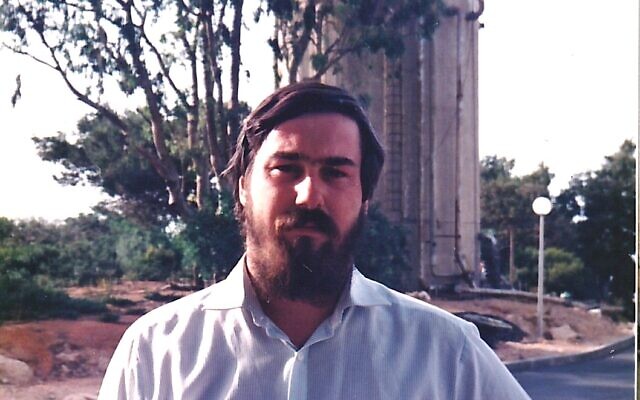

My first Yom Haatzmaut in Israel

It was 1988, Yitzhak Shamir was prime minister, and it was also Israel’s 40th anniversary, so Yom Haatzmaut was celebrated with even more than usual enthusiasm.

On my first Yom Haatzmaut in Israel, I thought I might die.

Let me explain.

It was 1988 and I was in Israel doing the ulpan program at Kibbutz Ma’agan Michael, on the cost just north of Caesarea.

I hadn’t finished converting to Judaism yet – I realised there was much more to it than religion, I was joining a people and so needed to get as much Hebrew language under my belt as possible.

I had been second in charge of the New Zealand Save Soviet Jewry campaign and since arriving in Israel I had already had the privilege of being at Ben Gurion airport to meet refuseniks like Yosef Begun and Ida Nudel when they were released by the USSR.

It was 1988, Yitzhak Shamir was prime minister, and it was also Israel’s 40th anniversary, so Yom Haatzmaut was celebrated with even more than usual enthusiasm.

After the solemnities of Yom HaZikaron, the exuberant atmosphere, the presence of so many blue and white flags and the inexplicable but fun custom of hitting each other with plastic hammers made the kibbutz a fun place to be.

As a seventh generation Kiwi from a military family who had grown up in a Naval housing area watching black and white British war movies full of stiff-upper-lippery and reading Commando war comics, a nation with so much experience of war was not entirely unfamiliar.

So parades, uniforms, talk of previous campaigns and remembering the fallen were a part of Israel I could identify with. Or so I thought.

Ma’agan Michael was a lovely place with fish ponds, banana plantations and even its own plastics factory, but a few years earlier it had been the scene of a horrifying act of terror – the coastal bus massacre.

In 1978 eleven Palestinian terrorists from Lebanon landed on the beach in Zodiac inflatable boats, where they came across an American nature photographer, Gail Rubin, who was taking photos in the wetlands.

They shot her dead, then proceeded inland, hijacked a bus and headed for Tel Aviv with their hostages.

It ended in a shootout with 38 dead. The story made a big impression on us overseas volunteers and ulpan students.

It was sobering to swim at a beach where a woman had been murdered in cold blood.

On the evening of Yom Haazmaut, I and my roommates were relaxing in our room when a sudden light flooded through the window.

“Ah, fireworks for Independence Day” said one of us.

It was obvious to me it was nothing of the sort, it was a flare, and that was confirmed a moment later when the siren on the kibbutz water tower started up.

We had no information but found out later that the IDF beach patrol which goes up and down the coast checking for this sort of thing had discovered a Zodiac pulled up into the bushes off the beach and the area was on full alert.

We had been told in our initial security briefing that if the siren went off, we were to go into our rooms, lock the doors and hide under our beds until told it was safe to come out.

Because a locked door will always defeat an armed terrorist and mattresses have the bullet stopping capacity of 8-inch steel plate, I thought sarcastically to myself as we did what we had been told and hit the deck.

I don’t know how long we lay under our beds on the wooden floor with the lights out, but it seemed forever.

There were flares going off and the sound of helicopters searching, but nothing else.

If there were any terrorists in the area and they decided the volunteer quarters looked as good a place as any to massacre some Jews, we were screwed.

I’ve never wanted a gun so badly as that moment.

Suddenly there was the sound of footsteps on the path outside. They got closer and then stopped outside the door to our room.

Time seemed to stretch out to infinity, and I felt a sharp metallic taste in my mouth. It was fear.

Part of my mind was in complete panic and unable to function, but as that wasn’t particularly helpful I simply locked it away and ignored it while I concentrated on rationally weighing my options.

Clearly it was overwhelmingly likely that it was just one of the kibbutzniks rather than a terrorist and I was in no actual danger.

But the chance that an AK47 wielding maniac was standing 10 feet away WAS NOT ZERO!

This possibility seemed to flip a switch in my brain.

I felt as if I had all the time in the world to formulate alternative plans of action – swinging my arms out to grab his feet if he came in, pulling the mattress over my body if he threw a grenade, that sort of thing.

I knew rationally these were unlikely to be effective, but there was no point in just giving up and waiting for death.

I felt weirdly calm, although definitely there was a part of my mind gibbering in terror, but it wasn’t terribly helpful, so I just ignored it.

My body tensed, in preparation for what I assumed would be a few seconds of action if it turned out my luck had indeed run out and I would be called on to sell my life as dearly as possible.

Of course, it turned out my basic risk assessment that it was simply some random guy out for an evening stroll in the middle of an emergency terror alert was correct.

Israelis can be like that, I learned.

The IDF found the Zodiac belonged to a diver who hadn’t bothered to take it back home with him at the end of the day, and everything returned to what passes for normal in Israel.

But I learned a valuable lesson that Yom Haaztmaut.

About Israel and about myself.

I realised that behind the Israeli swagger and confidence was the very real knowledge that danger and death are the potential price to pay for freedom.

Terror had come to this place before, and it looked like it might be happening again. This was not a theory from a textbook, this was us, here, now and terrifyingly real.

As for me, well there’s nothing like raw fear to burn away things that don’t matter.

I now realised in my gut that being a Jew comes with genuine risks.

Lying on a wooden floor under a flimsy bed waiting to see if you’re going to get shot or blown up will do that.

Becoming part of this people would mean my fate being joined to theirs, and this Independence Day experience was simply a taste of what that might mean in the future.

Since that 40th Yom Haatzmaut in Israel, being Jewish hasn’t been just a matter of faith for me – it’s an embrace of a collective destiny as one people, klal Yisrael.

It’s 36 years later and October 7 has happened and I’m still here, and you’re still here and none of us are going anywhere are we?

Am Israel Chai is so much more than a slogan.

comments