Past and present meet in Lithuania and Ukraine

Bruce Hill speaks to Shelly Freeman about the importance of preserving our past to connect with the present and future.

Melbourne Jewish woman Shelly Freeman (now living in New York) says her recent visit to the former Pale of Settlement to examine Jewish archival material and her work with the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research made her reflect on some of the lessons we can learn from the Jews of the past.

Freeman is chief of staff of YIVO (a cultural organisation and world-renowned Archive and Library), based in Manhattan.

When she first started at YIVO, Freeman was taken on a tour of the YIVO Archive.

She was shown some of the artefacts from the Holocaust collection, which is the largest collection of primary source Holocaust materials in the world outside of Yad Vashem in Israel.

“Growing up in Melbourne which is home to the largest population of Holocaust survivors per capita outside of Israel (and my grandparents and great-aunt were survivors), and seeing for example the logbook from Auschwitz Block 8 with the names of the inmates and the date they “exited” the camp – code for murdered – and other Holocaust-related materials brought the Holocaust home to me in such a tangible way that was chilling,” she said.

Freeman was also shown a poster from a Yiddish theatre concert in Melbourne on Saturday, April 15, 1939 being performed at the Assembly Hall on Collins Street in the city.

On the poster is the name A Mushin.

“I am very good friends with Pip and Jamie Mushin and sent them a photo of the poster to find out A Mushin was in fact their great-uncle. Seeing these materials firsthand offers such a visceral connection to the past and demonstrates the profound way to learn about and connect to our Jewish history through these primary sources,” Freeman said.

As part of her role, Freeman recently visited Lithuania and Ukraine, together with the YIVO CEO Jonathan Brent.

In the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius, they took part in a conference at the parliament marking the 80th anniversary of the liquidation of the Vilna Ghetto.

And in Ukraine they helped set up the process of digitisation and preservation of the archives of Yiddish writer S. An-sky, best known for his play The Dybbuk.

The An-sky Ethnographic Expedition (1912-1914) collected a wealth of objects and materials documenting Jewish life in the Pale of Settlement. The originals are held at the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine in Kyiv, at YIVO and in the Russian Ethnographic Museum in St Petersburg.

The collection is critical to understanding the daily lives and cultural legacy of the Jewish communities of Eastern Europe, which includes the heritage of many Jewish Australians.

Only a handful of scholars have studied the material in Kyiv, the existence of which is now threatened by the war in Ukraine.

“During our visit we saw where a Russian missile had landed next to the library some eight months prior. This project is urgent because if we don’t act quickly, we risk losing forever a critically important record of Eastern European Jewish life,” Freeman said.

The Vernadsky National Library has a collection of documents, photographs, artwork, sound recordings, ketubahs, folklore, religious materials, newspapers, songs and literature which shows Jewish life in the 1800s and early 1900s in the Pale of Settlement.

The library won’t allow any of the material to leave Kyiv so YIVO will work with their staff to train them on best practice of digitisation techniques and preservation.

“We will purchase all the digitisation equipment for them. Once the materials have been digitised, both YIVO and the Vernadsky Library will make them available on their respective websites,” Freeman said.

She also said she was touched at how the head librarian of the Judaica section at the library, who is not herself Jewish, looked after and respected these materials in a very professional and thoughtful way.

A big part of the YIVO trip was also to show solidarity with Ukraine.

YIVO undertook a similar digitisation project in Lithuania to reunite YIVO’s prewar archive, which had been split as a result of World War II between New York and Lithuania.

The Lithuanian government refused to give the YIVO materials found hidden in a church basement in 1989 in Vilnius to YIVO, which had relocated to New York during the war.

They said the materials and documents were created in Vilnius, which was backed up by the Lithuanian Jewish community who argued that it represented their cultural patrimony and should remain in Lithuania.

There was no definitive legal position regarding rightful ownership, so a commonsense solution was needed to preserve and reunite the YIVO prewar archive which contains approximately 4.1 million pages of original books, artefacts, records, manuscripts and documents.

“This material tells us how Jews lived, where they came from, how they raised and educated their families, how they created art, literature, music and language,” Freeman said.

This led to the Edward Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections Project (EBYVOC) starting in 2014, a seven-year, $US7 million project to preserve, digitise and reunite the prewar archive virtually.

She said after the completion of the EBYVOC in January 2022 the Lithuanians have been very cooperative and eager to do other projects with YIVO.

“I can say the people I have worked with have been incredibly genuine and see this history not just as the history of the Jews but part of Lithuanian history, albeit a difficult part of it in that the Lithuanians were actively involved in the destruction of the Jewish communities in Lithuanian during the war,” she said.

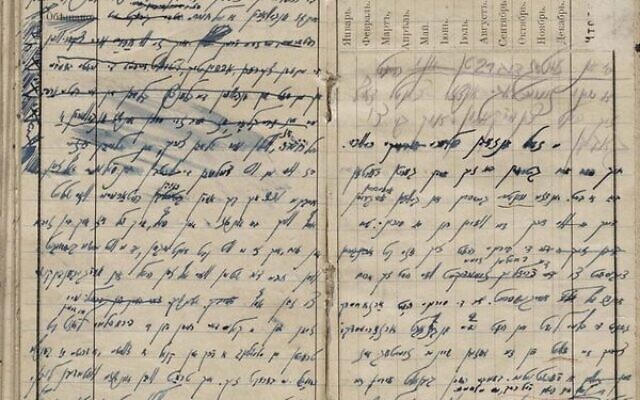

One of the treasures in the YIVO archives is the diary of Yitskhok Rudashevski, a 14-year-old boy who lived in the wartime Vilna Ghetto.

“He records the human depravity and suffering which he and his fellow Jews experienced which knew no limits; it is very difficult to read. But what shines through in the diary is his brilliance, his devotion to Jewish culture and how this sustains him during the darkest period of his life and his determination to survive,” she said.

Freeman said Rudashevski’s diary deftly explores his resistance to Nazi barbarity in the form of cultural resistance.

She said, “By engaging in his Jewish culture in the worst of times, he in his own way defied the Nazis’ regime. Even in the hellish ghetto, Rudashevski and his friends participated in youth clubs, history and folklore circles, mock trials and exhibitions, among other activities as a way to lift their spirits.”

Freeman believes his diary reflects not only who he was but the tragic loss of who he might have become.

When Rudashevski’s family found out about the impeding liquidation of the ghetto, they, with other families, hid in a malina (hiding place) but were caught and murdered in the Ponary killing field.

Rudashevski’s young cousin, Sori, somehow survived and after the war returned to the hiding place and found the diary.

Freeman said in a poignant note in his diary, Rudashevski wrote about how much he loved living in Vilnius – the summers, his friends, the life there and then he said, “And then one day something turned.”

“Obviously, we are by no means in the same situation as prewar Lithuania but that line about one day something fundamentally changing is how I feel to some degree about my life as a Jew pre and post-October 7,” Freeman said.

Freeman believes there are lessons for Jews today from these historical materials.

She keeps thinking of the line in Rudashevski’s diary where he talks about how much he loved his life in Vilnius and then one day things turned.

“In my lifetime I have never seen so much antisemitism in both Melbourne and Manhattan where I now live. This would have been unthinkable to me a few years ago,” she said.

Freeman considers that the materials in the YIVO archives show that antisemitism never goes away, it just morphs into different forms.

“However, what history also shows is that we are a people who ultimately survive even when it looks like things are stacked against us. Even as we face the worst threats and challenges, we survive,” she said.

When Freeman from 21st-century Melbourne looks at the Jewish material in the YIVO archives, she says she sees history repeating itself in the sense of the rise of antisemitism and Jew hate, but also that we survive and ultimately thrive.

“The message I choose to take from the lives of those living in those times and the history conveyed in these materials is that it is never an option to give up. I think about the paper brigade (a group of slave labour workers from the Vilna Ghetto who risked their lives to save Jewish materials from destruction at the hands of the Nazis), who despite everything going on around them they still believed in the future of the Jewish people,” she said.

They somehow believed Jewish life would go on after them, despite every account to the contrary, and that is why they risked their lives to rescue these materials for the next generations, Freeman said.

So, too, when Rudashevski took his diary even to his last cramped hiding place and continued to write in it, and during his time in the ghetto he continued to engage in his Jewish culture, refusing to give up.

“My role at YIVO has taught me in a very profound way the importance of our culture and material culture. It tells us who we are and instils in us a knowledge of our history, our traditions and our heritage,” she said.

Freeman often ponders how it is that we as a people have survived all these years despite the odds, and what are the factors that have led to Jewish continuity.

“One of the things I land on is the value we as a people have placed on preserving and defending our culture and heritage at all costs. The paper brigade could not save people, but they could and did save our heritage,” she said.

To find out more about YIVO go to www.yivo.org

comments