Antisemitism. For better or for worse, few topics engage (and enrage) Jewish communities as consistently as the world’s oldest hatred. But while many of us have an opinion on it, few are as qualified to discuss it as Dr Dave Rich. Having worked for nearly three decades at the UK Community Security Trust, and previously authoring The Left’s Jewish Problem: Jeremy Corbyn, Israel and Antisemitism, Rich’s latest book breaks down the world’s oldest hatred and explores what, if anything, we can do about it. I sat down with Rich to pick his expertise on this millennia-old topic.

There’s no shortage of books on antisemitism. Why did you feel this book had to be written?

There are loads of great books about antisemitism, but they all tend to fit in one or two categories. You have academic books that tend to be huge and quite dense, or you get books that are political polemics about antisemitism, but from a very particular angle with a particular argument to make.

I wanted to do two things. Firstly, [to write] a book for the general reader. There are a lot of people, certainly in Britain, who in recent years have come across antisemitism for the first time in their lives – because it has been much more prominent in politics, or it has come up in the workplace and the media – but who basically know nothing about it and have never really thought about it before. The book is written for them. Secondly, I wanted to address the subject of antisemitism from a different angle, which is to look at it as an idea. What is the central idea of antisemitism and what are the central themes through which it plays out in different times and places?

The other thing is, in the last few years there have been loads of new books about racism, especially since the murder of George Floyd and the rise of Black Lives Matter. If you go into any bookshop there will be dozens of books about racism, where it comes from, how it plays out in our society, and what people should do about it. There is no book like that about antisemitism. So I decided to write it.

You wrote in the book that there are assumptions about Jews hardwired into our civilisational culture. Can you talk a bit about that?

The central idea of antisemitism is that Jews are always up to something, and usually up to no good. You can’t really trust Jews, they always have an ulterior motive or hidden agenda. This is an idea that has been connected to really significant moments in history, and is present in really mainstream and influential culture throughout centuries. Go back to the narrative about the death of Christ and the blame that was placed on Jews. That’s a formative event in the creation of Western societies that we live in today.

So many of the assumptions that create the architecture of thought in our society come from Christianity, and so the Christian attitude towards Jews is really significant. A lot of the most common antisemitic tropes that we’re familiar with today can be traced back to the Middle Ages. It’s so embedded into the way our world was built that people just don’t notice it.

You say at the start of the book that it is about educating people and not blaming them. It seems like that’s increasingly uncommon today. People don’t want to educate, or think, “did they actually mean what they said?” Why did you explicitly mention in the book that you’re not here to blame, you’re here to educate?

I think most people both want to be good people and be thought of as good. It’s important to give people an opportunity to learn and understand what they’re getting wrong. I’m also trying to reach an audience that has never really thought about antisemitism before, and may well have fallen for these ideas themselves or expressed views that we might think are antisemitic. If your initial response to that is to condemn, then you’re much less likely to reach those people.

I want to reach people and say the reason you come out with these things is not because you’re evil, it’s because you’re a product of your society, and these ideas are just so common in society.

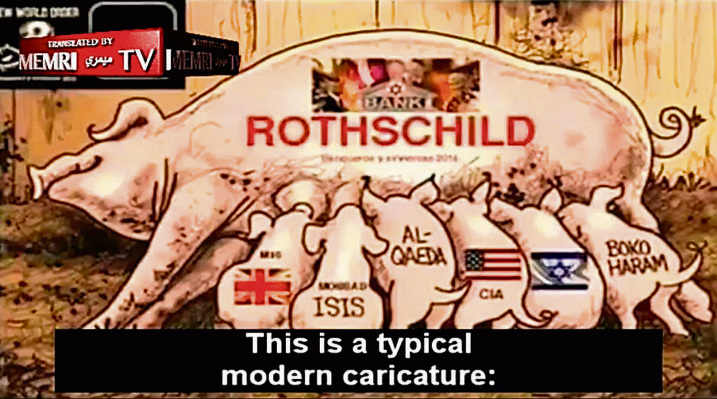

I do a lot of antisemitism awareness training. I speak to mainly non-Jewish audiences, and the main thing I take away from all this is that hardly anyone knows anything about antisemitism. If people don’t even know where the Rothschild conspiracy theory comes from, can you really blame them for sharing a Rothschild video they’ve seen on TikTok because they thought it was funny? You have to give people a chance to learn.

“If people don’t even know where the Rothschild conspiracy theory comes from, can you really blame them for sharing a Rothschild video they’ve seen on TikTok?”

It seems that when it comes to antisemitism, the public, by and large, often isn’t quick to come to our defence. How does that fit into this idea you write about that people are inherently good people who abhor antisemitism?

You’ve got to remember, we aren’t the only people trying to reach these audiences. There are lots of other people – much more harmful actors – who are creating and spreading engaging content and ideas. And the ideas they are trying to share resonate. They stick precisely because they’ve been around so long. If people see videos on YouTube about rich Jews like George Soros using their money to manipulate immigration, at a subconscious level that will resonate because it fits into the groove of how our societies have taught us to think about wealthy Jews who are politically engaged. It makes sense at a deep level because it’s so familiar.

It resonates in the way that if it was about other minorities, it wouldn’t necessarily resonate. If there were conspiracy theories about rich Black people using money to control politicians, people might look at it and think, “well that goes against the grain of what I know about Black people”. It doesn’t fit the stereotype.

I want to get your thoughts on the “canary in the coal mine” analogy. While it may be true, it’s also inherently dehumanising because it says if Jews are attacked, non-Jews should care because it means that people who actually matter may be hurt next. How should we approach this analogy?

I don’t really like the analogy because I don’t want to be a dead canary, and that’s the role that’s allocated to Jews. What that means is our lives are of less value than the lives of others who will be saved by the forewarning that antisemitism brings. But let’s be charitable. I don’t think most people who use the analogy mean it in that way. I think what people mean is you should be alert to antisemitism even if you aren’t Jewish because it affects Jews first, but it endangers everyone in the end – and I do think there’s truth in that.

“The central idea of anti-semitism is that Jews are always up to something.”

There are lots of examples throughout history where falling for antisemitism has in the end been very damaging to that society. This is partly because Jewish communities have been able to contribute greatly to societies they’ve lived in if they’re allowed to flourish. But it’s also because antisemitism at its heart is a conspiracy theory, and conspiracy theories are a false way of understanding the world. If your way of understanding the world is that Jews are to blame for everything, you’re not really going to get to the bottom of what your actual problems are and come up with realistic solutions to deal with them.

You wrote in the book, “Even the most powerful Jews were only ever power-adjacent, and it could be quickly whipped away from them if the wind changed”. Do you think that’s true for Jewish Diaspora communities today?

Two of the worst catastrophes to affect Diaspora Jewry are the expulsion from Spain and the Holocaust, and they both happened in countries where Jewish communities had been incredibly well integrated. History should show us that a Jewish community with that level of integration, security, belonging and prosperity will always have the potential to collapse.

You write that millennials are more prone to anti-Jewish views than pensioners. What do you think this says about the future for the Jewish Diaspora?

There’s quite a lot of polling evidence in Britain that if you’re under the age of 35, you’re much more likely to believe conspiracy theories about Jews than if you’re over the age of 50, but you’re also much more likely to believe conspiracy theories about everything else if you’re younger and if you rely on social media as your main source of news and information. People below a certain age are getting their news from TikTok and Instagram, and people above a certain age never use TikTok and Instagram. That’s a big problem.

The question of the future of Diaspora Jewry is always tied up with the question of the state of societies that we live in. What does it mean for liberal democracy if we don’t have a shared understanding of what is true and what is a reliable and trustworthy source of information? If that collapses, then things turn darker for Diaspora Jews, as they’ll turn darker for anyone else who cares about liberal democracy.

What advice would you give people for fighting against antisemitism?

Knowing what we’re talking about is really important. A lot of Jewish people don’t know a lot, so we need to educate ourselves in order to educate others.

For us as Jewish people, one of the most important things in breaking down discrimination and prejudice is human interaction, and we are only small communities, but the more we can get out there and build those human relations, especially amongst kids, is really important.

There’s been this explosion of Jewish schooling in Britain in the last 30 years. It’s been incredibly successful and had a lot of positive benefits within the Jewish community, but one of the consequences is that there are far fewer Jewish kids in other schools than there used to be, and so the non-Jewish kids in those schools don’t have Jewish friends. What can we as a community do about that? It would benefit us to find ways to build really meaningful contact and engagement at a human level with the societies that we live in.

Josh Feldman is a Melbourne-based writer.

comments