Fashion has a way of defining an era, of defining a person. Clothes tell a story. And the clothes from Auschwitz-Birkenau tell a story too – the ones taken from the prisoners the moment they arrived, but also the clothes that were sewn, on site, for elite Nazi women.

Author Lucy Adlington’s new book, The Dressmakers of Auschwitz tells the tale of the mainly Jewish women and girls who were selected to work in the Upper Tailoring Studio, designing and sewing beautiful items of clothing worn by Nazi Berlin’s upper echelon.

It’s a story that hasn’t yet been told.

The power of clothes

Adlington is a clothes historian, so the story of the seamstresses is one that she felt privileged to tell. Through her research, Adlington was faced with the peculiar conundrum of the Nazis viewing Jews as a subhuman race, who were not allowed to touch clothes in retail stores for fear that they will defile them, contrasted against the Kommandants requesting the dressmakers in Auschwitz to design and stitch a dress for them.

It’s like the juxtaposition between stripping people when they first arrive at concentration camps, taking away their identities, to then forcing them to make clothes for those in power.

“The Nazis were absolutely well aware of the power of clothes,” Adlington said from her home in England. “They knew what could give you status and what could take it away.”

The last remaining survivor

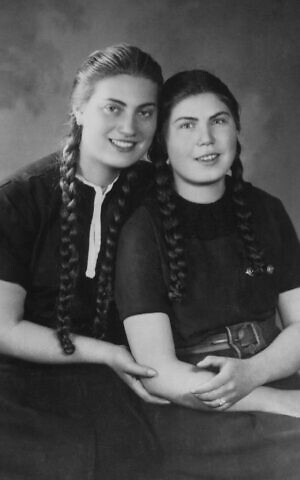

Several of the dressmakers that Adlington talks about in The Dressmakers of Auschwitz were on the second transport from Slovakia.

Photo: Tom Areton

Speaking to families of survivors including the last surviving seamstress Mrs Bracha Kohut, Adlington said she was touched by the show of solidarity constantly shown by the women, whether that was stitching up mistakes at the studio, joining the resistance or listening to each other when they just wanted to talk about their families.

When asked how she felt speaking to Mrs Kohut, Adlington said it was a very intense week. “How powerful it is to make a connection between someone we might perceive as this old woman, but she’s not. She’s the young woman from the story. She’s the 20-year-old who was stripped on arrival. She’s the one who said, ‘We’re going to be having coffee and cakes, wait and see’.”

Adlington explained there was a mixture of skill among the women at the Upper Tailoring Studio. “These are ordinary people, they’re ordinary young women and girls,” she said. “Some of them were very good seamstresses, some of them barely knew how to sew when they were taken in and rescued into the salon. But they’re not ordinary to the people who love them, and they’re not ordinary in what they represent.”

The memories attached

Researching the history of Kanada, the warehouse used to store stolen belongings of prisoners, really hit home for Adlington. “When the young women are sorting through, they’re having to bale up coats or lingerie or children’s frocks, and one of the girls finds her own coat,” she said. “These were not coats they’d worn into the camp; they were coats they’d left at home with the family.”

Of course, this meant her family had been deported.

For Adlington, it is the memories attached to garments that matter.

And the clothes from Auschwitz-Birkenau tell a story too – the ones taken from the prisoners the moment they arrived, but also the clothes that were sewn, on site, for elite Nazi women.

“All that remains is this garment that can’t talk, it doesn’t have the information written on it, it’s just yarn. But it holds all of those memories.”

One of the most memorable garments she owns, as part of her collection of vintage and antique clothing spanning 250 years, is a suit sewn by one of the dressmakers who survived.

“It doesn’t have a label on it. It doesn’t say ‘Hunya sewed this’, ‘Hunya survived Auschwitz’, ‘Hunya kitted out the Kommandant’s wife,” Adlington said. But when you look at the stitches and the silk, that’s what makes the connection.

Ultimately, we understand how clothes make us feel and how they matter to us. We recognise our dad’s favourite cardigan or our child’s favourite dress, and we thrive on that human connection.

For the dressmakers of Auschwitz, they were doing meaningful work, supporting each other. They weren’t being degraded with hard labour. “That gave them a sense of humanity and dignity, which meant that they had the capacity and the privilege to be able to help others,” Adlington mused.

It’s a story about a group of brave women who quite literally, sewed to survive. And Adlington, who is not Jewish, was the perfect person to tell it. As she said, “If not me, then who?”

The Dressmakers of Auschwitz is published by Hachette Australia, $34.99 (RRP)

comments