The deep bond between our communities

"I want to reciprocate by helping … overturn a similar lie which is now being told against the Jewish people: that they have no connection to the land of Israel; that they are 'settler-colonialists'."

The feeling of solidarity between Australia’s First Nations and Jewish communities goes back nearly a century, to December 6, 1938, when Yorta Yorta man William Cooper led a march to Melbourne’s German Consulate protesting the atrocities of Kristallnacht. Given how much of the world turned a blind eye to the evils of Nazism in the 1930s, this was a truly astonishing act, emblematic of Indigenous Australians’ capacity for empathy and commitment to justice.

In 2018, marking the 80th anniversary of Cooper’s march, Jewish groups assembled “to honour William Cooper’s memory by making a similar stand on behalf of his people and their future. We do this by calling on our elected leaders to work together to establish a just Treaty that recognises and acknowledges our nation’s First People and ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a lasting voice in our national Parliament,” according to event organisers.

This history informs Indigenous leader Nova Peris’ recent characterisation of Jewish Australians as “the most committed friends and allies” of reconciliation. As an Australian Jew, I can attest to how my inbox overflowed with invitations to talks, discussions and opportunities to support the Voice to Parliament last year.

Peris went on to say, “I want to reciprocate by helping … overturn a similar lie which is now being told against the Jewish people: that they have no connection to the land of Israel; that they are ‘settler-colonialists’.”

New York Times columnist Bret Stephens (6/02/24) described the Jews as an “ethnic group… that can unmistakably trace its language, culture and religion to the same places from which it was long exiled and now inhabits and governs”, pointing out that “virtually every Israeli can read Hebrew inscriptions on Jewish coins found in archaeological sites throughout Israel dating back more than 2000 years.”

To understand the nature of and challenges to Jewish indigeneity, one might imagine that the British invaders, rather than moving Indigenous communities to what they considered less valuable lands, instead expelled them from Australia. Imagine further that these First Nations people were shunted from nation to nation, subject to slaughter, vandalism, rape, every kind of abuse, expulsion and, ultimately, genocide.

And what if those exiles, after many centuries, returned, now in their millions, to Australia, carrying with them the timeless culture that they had carefully shepherded for centuries. On returning, they would find the country that they’d carried in their hearts – the rivers, the forests, the wildlife – waiting for them. Would they not rejoice and kiss the earth, much as Jews from around the world do today when stepping onto the tarmac at Ben Gurion International Airport?

Within that tale of indigeneity lost and found lies the sorrows of two long-suffering peoples. The Holocaust inflicted last century upon the Jews of Europe is the worst genocide in history, though only the most recent of a millennium of efforts to exterminate Jews. Yet, the genocide of Indigenous Australians is equally horrific. The extermination of Indigenous Tasmanians, to take but one example, is comparable in its extent and its brutality, lacking only the industrial methods employed by the Nazis.

Jews and Indigenous Australians also share a history of efforts at ethnic cleansing and erasure of their culture. We are aware of the tragic history of the Stolen Generation and how Indigenous children were forced to don Western attire and attend Christian schools. In Germany, in the 16th century, to take but one example, clerics advocated that Jewish children should be taken from their parents, Jewish books destroyed, and Jews in general be expelled from Christian lands. During the Spanish Inquisition, Jews were ordered to convert to Christianity or be expelled from Spain, leading hundreds of thousands to abandon either their faith or their home.

Stephens closed his column with the point that “History is lived forward, not back, and the goal of politics and diplomacy is to make life as liveable for as many people as possible.” Living forward is a challenge both peoples face.

Indigenous Australians face an uncertain path after a majority of Australians rejected the deep spirit of reconciliation embodied in the Uluru Statement From the Heart. Supporters of the Voice to Parliament across the nation are still nursing their broken hearts.

The Jewish people have learned that the horrors that marked their history for a thousand years cannot be avoided, not even within a nation of their own. Yet, safety for the Jews cannot come from inflicting vast suffering upon the Palestinians. The world waits for a moral stance of constraint and a leadership with a vision of peace to emerge.

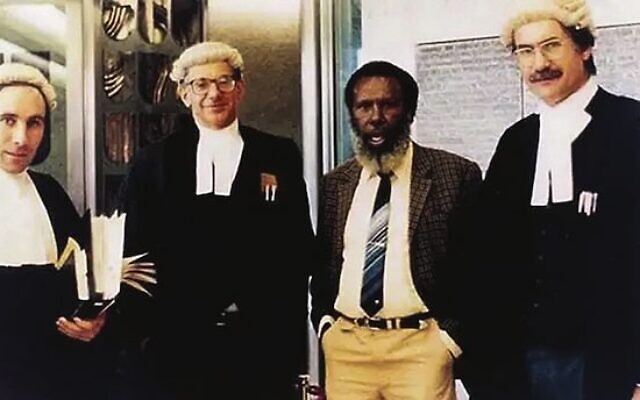

Martin Luther King Jr famously said, “The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.” That arc is bent by the righteous among us. Certainly, William Cooper was a standout in that regard. Nova Peris cites Jewish attorneys Jeff Sher and Ron Castan, leaders in the cause of Aboriginal land rights, saying, “As proud Jews, they understood what it is like for people to have an eternal connection to a land.”

Solidarity, self-sacrifice and deep compassion will continue to bind these communities together, knowing that all those fighting against prejudice and injustice must find common cause.

Dan Coleman is a former political columnist for the Durham (North Carolina) Morning Herald. He is the author of Ecopolitics: Building A Green Society. He lives in Melbourne.

comments