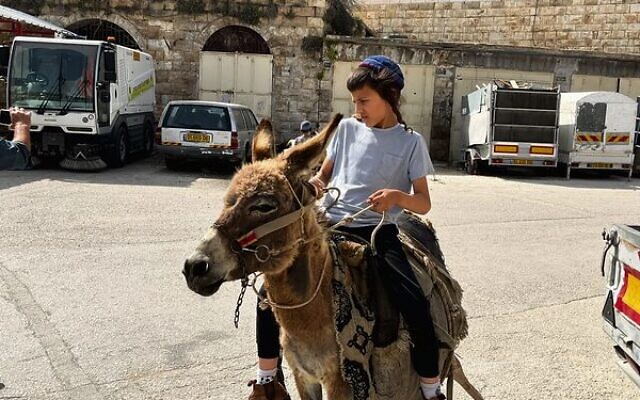

I saw him in the corner of my eye. Kippah shruga (knitted kippah), sun dappled hair, long payot, wool vest, flowing tzitzit, jeans and Australian Blundstones.

He was wearing his tefillin, the armbands digging deep into his bronzed arm. The archetypical hilltop settler, a hippy if he was in any other country.

As our guide explained the horrendous murder of 29 Muslim worshippers by Baruch Goldstein from nearby Kiryat Arba, outside the Tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron, he sauntered up to us. His wife and small child were playing on the grass nearby. Stopping, he looked at us and proclaimed, “Baruch Goldstein is a martyr. He should have killed more. We should kill all the Arabs!”

My wife, Sandra, and I have made many trips to Israel, but we had not been to Hebron, a city that is in the epicentre of the conflict over the disputed territories. We chose to take one of the few tours that presented both the Jewish and the Arab narrative, through tour company Abraham Tours. We had two guides – one Israeli, one Palestinian – each showing a different half and perspective of the city. They claim the tour is political but objective, with participants free to form their own opinions.

We meet in the busy lobby of the Abraham Hostel in the centre of Jerusalem. There are 17 of us from all corners of the globe. Sandra and I are the only Jews, and the only Australians.

Our Jewish guide, Eliyahu, a Ba’al Tshuva, who was a secular pro-Israel activist at UC Berkley before making Aliyah, ushers us onto a bullet-proof bus for the journey to Hebron.

We leave Jerusalem and travel through the beautiful, terraced hills dotted with Palestinian towns and villages and Jewish settlements with their distinctive red tiled roofs. The roads are good, reflecting the investment in infrastructure by successive Israeli Governments, in the West Bank.

The further we travel, the greater the presence of the Israeli army. All junctions have pill boxes with soldiers guarding. Despite the concrete and their full battle gear, they look vulnerable.

The first shock for us is the distance between Kiryat Arba and Hebron. I had always imagined the town to be on a hill overlooking Hebron. After driving through, we realise that Kiryat Arba and Hebron are umbilically joined, the only separation being a security barrier. This symbiotic connection is emblematic of the complexity of a resolution to the conflict.

Hebron is the second largest city in the West Bank, after East Jerusalem, with a population of 215,000 Palestinians and approximately 700 Jewish settlers concentrated on the outskirts of its old city. The Hebron Protocol of 1997 divided the city into two sectors: H1, controlled by the Palestinian National Authority, and H2, roughly 20 per cent of the city, including 35,000 Palestinians, under Israeli military administration.

All security arrangements and travel permits for local residents are coordinated between the Palestinian National Authority and Israel via the Israeli military administration of the West Bank. Thus, Hebron is on both the frontline of conflict as well as cooperation between Arab and Jew, making it a microcosm of the Palestinian-Israeli conundrum.

Once scrutinised and through the barrier between Kiryat Arba and Hebron, the change is immediate. The Old City of Hebron is unkempt and in many parts empty. Once bustling market streets have been vacated to assure the security of the Jewish enclave, often as a response to terrorist incidents. There is barbed wire at many points, and netting above the market streets to prevent rubbish, stones and other projectiles being thrown by both sides.

After obligatory visits to glass-making and ceramic shops, both industries Hebron is renowned for, we were brought by our Arab guide, Marlwa, to the Old Hebron Museum which is housed in the old “Palestine Hotel”, a beautifully restored building from Mandate times. We meet Tareq Tamimi, the general manager of the Hebron Chamber of Commerce, who takes us through the displays, the last being on Israeli policies and violations against the Palestinian residents and urban heritage.

We are then seated while Tareq tells us about the history of Hebron under occupation. It is hard to listen to. His narrative is filled with exaggerations, and at times, outright disinformation. Despite this, we have agreed between us to not interfere with his narrative or any other we hear during our time on the Arab side.

At one point, he explains that the two stripes on the Israeli flag are the Euphrates and the Nile, insinuating Jewish intentions. At another point, he claims no Jews were present in Israel before the Europeans Jews came in the early 20th Century. He does not deny the Hebron massacre of 1929 or riots in 1936-39, but claims many residents helped their neighbours (partially true). There were many other examples, exaggerated or false, in amongst the real suffering that Hebron’s citizens have experienced under occupation.

Following lunch, we enter through turnstile security gates, one of 18 checkpoints set up by Israel, under the watchful eyes of Border Police, into the Jewish compound. Beginning in 1979, Jewish settlers moved from Kiryat Arba to found the Committee of the Jewish Community of Hebron in the former Jewish neighbourhood near the Abraham Avinu Synagogue, and later to other Hebron neighbourhoods including Tel Rumeida. They took over the former Hadassah Medical Centre, Daboya Hospital, now Beit Hadassah in central Hebron. Today approximately 500-800 settlers are protected by a brigade-size military presence.

We are taken to the Hebron Visitors Centre in the beautifully renovated Hadassah Building, a hospital until abandoned in the aftermath of the 1929 Arab massacre. We are escorted through a museum that tells a familiar story from biblical times to modern, of the Jewish presence in Hebron. We then meet with Dr Noam Arnon, spokesperson for the Jewish community of Hebron and a noted historian and scholar of the city. While the account is more factual than that which we experienced on the Arab side, it presents a very singular perspective, with little mention of the Arab inhabitants other than motherhood statements of their preference for Jewish rule, or acts of terrorism. No mention is made of Jewish terrorism, including Baruch Goldstein.

After the talk we explore the compound. It feels run-down except for some newly built or renovated buildings. Many settlers carry a gun. The dominant dress-code is black or khaki. There are soldiers everywhere, often lounging, listening to modern music and exercising. It feels more like an army base in parts. We talk to them; they are all looking forward to completing their service.

There is no economic activity and family life is hidden to us. From the top of its tallest building, we can only see Arab Hebron surrounding us as far as the eye can see. Despite the history, we cannot escape the feeling that it is an unwelcome and unsustainable presence, existing through force of arms.

Our tour concludes with a visit to the Jewish side of the Tomb of the Patriarchs and our encounter with our aforementioned menacing modern Orthodox disciple. The group is visibly shaken by the encounter. We are devastated that they should experience such a fanatical perspective of Judaism. How could they form any positive opinion after hearing his outcry?

On the bus back to Jerusalem, the group is quiet. I chose this moment to get up, with Eliyahu’s permission, and speak to them about their experience. They were confused and upset by what they had seen and experienced (as were we). They all agreed the issues were complex. The different narratives reflected differing perspectives and accentuated the complexity of a resolution. Regardless, they all left feeling that Israel, despite the complexity of issues and history, is an oppressive force, ruling over a desperate people. Sadly, no amount of spin can change that.

As Rabbi Donniel Hartman said on his recent visit to Australia, “We are occupying another people. Whether we are occupying another land is up to opinion.”

We wondered how they would feel, later in their trip, when they were enjoying the free lifestyle of Tel Aviv, and whether this experience would change that. It did for us.

Jewish Sydneysider Danny Hochberg sits on a number of Jewish communal boards.

comments