‘This is about our story’

Danny Hochberg finds camaraderie while helping Israel’s soldiers

It is my first day volunteering for Sar-El. I am based at Tel Hashomer, one of the largest army bases in Israel. We have finished a full day’s work and are crowded together in the common room. Our Madricha enters, her brows knotted, her face stern. We are asked to immediately join soldiers who are preparing flak jackets for troops in the South. Because we had worked 10 hours already, the Madricha asked for volunteers only. Nobody declined the request.

Sar-El is a program that is run in conjunction with the IDF Logistics Corps, which involves participants volunteering on different bases, doing non-combative work. Volunteers live on base, wear uniforms, eat and work with soldiers.

Since the start of the war, the majority of volunteers from overseas have cancelled, but they have been replaced by Israelis, who volunteer for a day. I arrived in Tel Hashomer with a large volunteer group of Russian emigres. While they go to their allocated work, I am given a cot in a room I share with others I am yet to meet. I pick-up an ill-fitting uniform from a pile, regretting my haste for the rest of the week, as I constantly hitch my pants above my hips and my shirt hangs on me like a rag cloth.

I am sent to work with Noam, who manages one of many warehouses in which we are allocated. He is a civilian contractor, who has worked here for 13 years. He has worked with Sar-El for much of this time, and tells me that due to shortages, he is often entirely reliant on the volunteers. I am working with Dave, a Texan Jew with a daughter living in Modiin, who takes me under his wing and helps me understand my role, from how to work to what to do in the line-up for food at lunchtime. An ex-Marine, he’s Texan to the core: Trump, the big pick-up truck, guns at home. For all that, he is a softie, and I appreciate his advice.

I quickly learn how to navigate the zeitgeist. Eliyahu in procurement, sits behind a desk, moving like a serpent to the electronic music. His balding palette, gawkey glasses and kippah are the obverse of the pumping music. His sidekick, Igor, a stoop-backed, wheezing Russian Jew is a bristly character who I make a big effort to win over. If there is a computer in the warehouse, it’s not being used. Everyone refers to Igor, who knows where everything is, and seems to record the inventory movement entirely in his head. Micha and Yuval have finished their army service, but chose to stay on to help. They both worked in the surveillance unit, watching the Gaza fence. Both knew friends they served with who were killed on the base at Nahal Oz.

The rhythm of the day, with the exception of the occasional air raid alarm, is typical of any base. Breakfast and then Misdar (Assembly) in the morning, with a flag raising and singing of Hatikvah. We work through to lunchtime which lasts an hour. Then it’s back to work until 6pm and dinner, followed by an evening activity. The work is tiring and the unseasonal heat adds to the challenge. But all of us talk about it in terms of saving lives, and that motivation overcomes the inevitable monotony.

The majority of the group I am with are American. Most are veterans, having volunteered many times to serve in Sar-El. There are also two Norwegians and a few other non-Jews. They are evangelical Christians, committed to the Jewish State. They will often bless us all, and talk in messianic terms. They are good people, and their presence is welcomed.

The rest of the group are American Jews. Some live part of the year in Israel, and part in the States, to be closer to children and grandchildren. Lea and Bernie Weinberger live in Jerusalem, but have a place in New Jersey. Clare and Monty are from Montreal. Marvin, a dentist from New Jersey, tells me his mum was liberated from Auschwitz, like mine. We speculate as to whether they may have met. Marty is a scholar in Near-Eastern studies, and tells me he worked in the Iranian Embassy in the 80s. Jim is an eight-timer from DC. They’re a good bunch. Committed and hard working. On my third day I am surprised when Assaf from Melbourne joins us. He is Israeli born, and a tennis coach back home. When he arrived, he sadly went straight to a Shiva in Petach Tikva, for a friend who lost his mother, brother, and his brother’s 9-month-old daughter on Kibbutz Be’eri. That is enough motivation.

Each day we are joined by day workers. One day there is a group of young, fresh faced American Yeshiva bochers from Yeshiva Torah v’Avodah in Baaka, Jerusalem. They are an enthusiastic bunch and we join them in singing and dancing Am Yisrael Chai. The Rosh Yeshiva spoke to us all, and his words resonated: “We are it. This is about our story, our family, our people. And you are part of this!” The next day we had a group from Ra’anana. I worked with Dani and Yael, whose accents made me think of Sydney. Both came from Johannesburg, and between them had five children in the army.

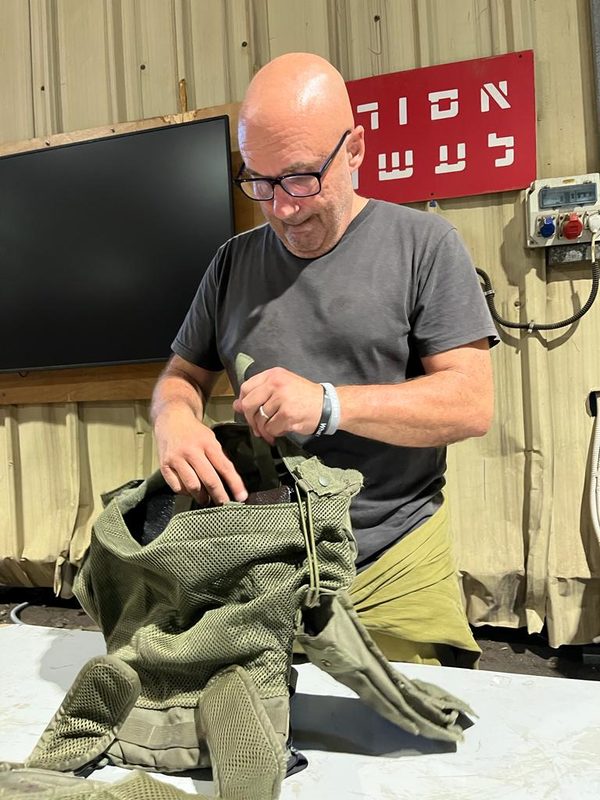

The night we all volunteered to help “build” the flak jackets was emotional. We were transported to a warehouse where there were at least a hundred young soldiers. We were led by combat officers who oversaw the process and were responsible for quality control-we needed to get this right. We created a production line, with each given a different task. I was tasked with opening up the vest and placing the ceramic plate in the front compartment, securing it and closing it. Despite the stifling heat, we worked quickly and efficiently. I admired the work ethic of my group, despite their tiredness and many of them being older than me. Support came in the form of great music being pumped from the speakers, constant encouragement, food and water from the younger soldiers, and a real sense of mission.

I won’t deny that I found the job traumatic. In each vest I saw a young boy, and my eyes welled with tears as I thought of the danger they would face when they placed these over their heads. With each one, I said a silent prayer to keep its wearer safe and bring him home into the arms of his family.

The routine is often broken by the wail of the air raid sirens. I have down-loaded the Home Command app, which rings whenever rockets are launched. It tells me the location and number. When the siren sounds, some run, the more confident amble. There are many of us and the bomb shelters fill fast. We can see the vapour trail of the rockets and the plume of smoke in the sky above us, following an impact by Iron Dome. The booms that follow shake the shelter while birds screech and fly in panic, directionless, looking for sanctuary from the predators from Gaza. The sirens, the hiss of missiles and the boom are becoming normal for me. Erev Shabbat I travel by train to stay with friends, and the driver requests we all lay down in the aisle as the rockets rage above us.

On the way to Hashalom Station, I pass the protest tent embassy for those kidnapped and am given a yellow ribbon to tie to my bag. Citizens and family of those kidnapped maintain a 24 hour vigil. Cars pass tooting their support, volunteers tie the ribbons to their side mirrors. At the Azrielli centre an enormous digital signboard announces the names of cities with communities that support Israel and pictures of their rallies. Among them is Sydney, with a picture of the rally I helped organise at Dover Heights and one of the Opera House lit-up in blue and white.

As I enter Matan, the small town where my friends live, a sign on the gate of Yarchiv, the moshav next door, has a big poster asking for the return of a daughter from the community, Liri Albag. Liri was a surveillance soldier at the Nahal Oz base, who was taken captive by Hamas terrorists on October 7. In Israel, you are never far from the tragedy.

Israelis are a resilient bunch. When I was here in May, I attended protests for Democracy, and feared for the future of civil discourse. I return to a country at war, more united, but angry, grieving and fearful for the challenging days and weeks ahead, let alone the future. There is optimism that victory will be ours, but fear at what cost. Society and the economy are seriously disrupted, adding to the trauma.

I want to write of the hostages as well, but I have no words. Maintain the rage against those that would wish us destruction and stay safe. Am Yisrael Chai!

Jewish Sydneysider Danny Hochberg sits on a number of Jewish communal boards.

comments