Watching Isi Leibler in action in Moscow

'Isi Leibler was a giant of world Jewry. Watching him in action was a rare privilege. May his memory be a blessing and an inspiration'.

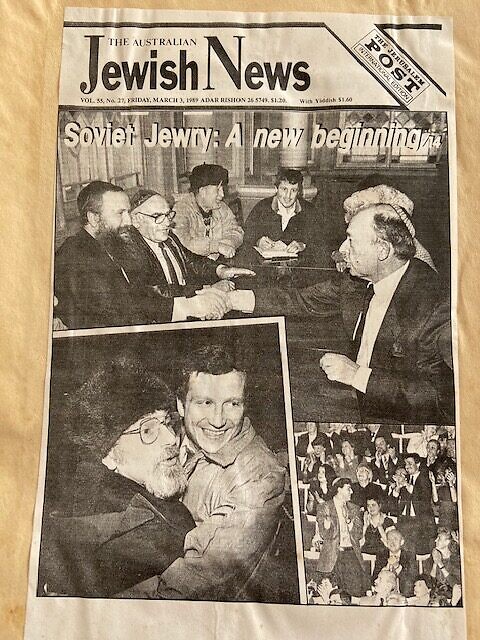

THE phone rang in Isi Leibler’s hotel room. We were in Moscow. It was February 1989 and the temperature outside was a numbing minus 27. I picked up the receiver. It was a senior officer at the Australian embassy.

“Please inform Mr Leibler I’ve managed to arrange the meeting with Mr Rechetov,” said the embassy officer. “He can bring two people with him.”

I relayed the information to Leibler, who had been awaiting confirmation of this meeting for some weeks. His cryptic response: “Tell him there will be nine of us in the Australian delegation.”

All these years later, my ears are still smarting from the eruption at the other end of the phone. The printable portion was along the lines of: “Kindly impress on Mr Leibler that it’s taken me months to get this meeting!”

Leibler’s next response was even more cryptic: “Tell him it’s nine or I’m not coming!”

Guess who blinked. The meeting, with all nine of us, was in the Kremlin – you pinch yourself that you’re inside those walls!

It was with Yuri Rechetov, deputy chief of the Division for Humanitarian Issues in the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Leibler had brought me to Moscow as a senior editor of The Australian Jewish News to report on the historic achievements which he was in the throes of securing.

After exchanging pleasantries, he presented Rechetov with a list of 45 names, each one a refusenik – Soviet Jews who had been declared prisoners of the state for the crimes of applying to emigrate to Israel, studying Hebrew or simply practising their faith.

“We have over a million Jews in this country,” noted a bemused Rechetov. “Why do you care about 45?”

“We care about every one of them,” responded Leibler evenly. “As fellow Jews, we are responsible for every one of them.”

The visit was one of many which Leibler undertook during the dark days of the Soviet empire in the 1980s, having spearheaded a campaign which saw Australia become the first country in the world to raise the plight of Soviet Jewry at the United Nations. He utilised the trips to press the case for freedom for Jewish dissidents and refuseniks, forming close connections with a large number in the process.

That visit included an experience which remains embedded in my psyche as one of life’s memorable moments: Leibler organised the first legitimate concert of Jewish music in Moscow since the 1917 Russian Revolution.

His passing leaves a void that will be felt for years to come.Vale Isi Leibler.https://ajn.timesofisrael.com/the-gold-standard-of-jewish-leadership/

Posted by The Australian Jewish News on Wednesday, April 14, 2021

Held in Moscow’s magnificent, if ageing, Tchaikovsky Hall, the concert attracted 3000 Jews. Lining up in knee-deep snow and indistinguishable in their thick coats, leather boots and Cossack-style fur hats, some had travelled for four days by train from Siberia, spending a significant component of their wages to do so, such was the moment of the occasion.

The performers included the talented Aura Levin from Melbourne, while the final act was Israel’s Dudu Fisher, who played Jean Valjean in Israel’s version of Les Miserables. With fedora-wearing KGB officers menacingly evident in the front of the hall, Fisher caused a frisson to ripple through the audience when he began by pointedly observing, “I’m sure these walls have never heard chazanut before.”

There were refuseniks scattered throughout the auditorium, including Yuli Kosharovsky seated near me – an engineer who had been fired from his post 16 years earlier after applying to migrate to Israel. And then Fisher delivered the most stirring and meaningful rendition of Bring Him Home from Les Miserables that I instinctively knew I would ever hear, causing tears to flow as the power, the poignancy and the painful relevance of those lyrics sank in. It was truly a moment in time.

Leibler’s final act on that trip was yet another historic coup – establishing the Solomon Mykhoels Cultural Centre, with then-World Jewish Congress president Edgar Bronfman doing the honours. The centre was named for Solomon Mykhoels, artistic director of the Moscow State Jewish Theatre. However, he was also chair of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, and as Stalin pursued increasingly antisemitic policies, Mykhoels was assassinated on Stalin’s orders. His death was presented as a hit-and-run accident, whereas in fact he was abducted and killed, his body dumped on the road and run over by a truck.

Isi Leibler was a giant of world Jewry. Watching him in action – whether in meetings in the Kremlin, turbulent exchanges with Soviet officialdom or negotiating humane outcomes for Soviet Jewish activists – was a rare privilege. May his memory be a blessing and an inspiration.

Vic Alhadeff is outgoing CEO of the NSW Jewish Board of Deputies.

Get The AJN Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

comments