We Ukrainians say, ‘Never again!’

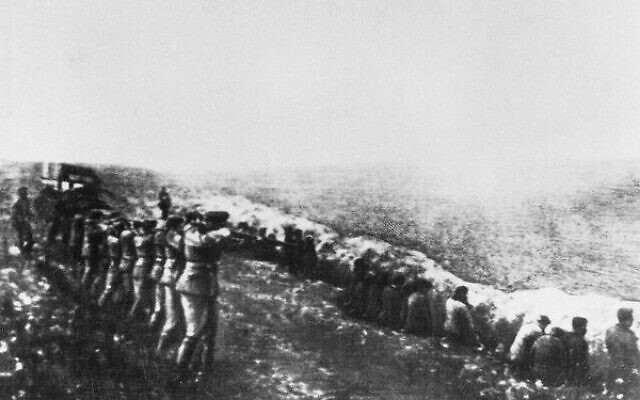

Babi Yar was the most notorious of the “Holocaust by bullets” actions that characterised Nazi crimes in the east during Word War II.

IT is now 80 years since the shooting of tens of thousands of Jews at Babi Yar.

On September 29-30 in 1941, more than 33,000 Jewish men, women and children were shot in a ravine outside Kiev in Ukraine. Over the next three years 120,000 Jews, Allied POWs, Ukrainians, Russians and Poles would die there.

But above all, it is Babi Yar as a tragedy of the Holocaust that we commemorate in September 2021.

Babi Yar was the most notorious of the “Holocaust by bullets” actions that characterised Nazi crimes in the east during Word War II.

Across Ukraine, Belarus, the Baltics and Russia, entire Jewish towns and villages were liquidated. Today, Babi Yar has come to represent many local events that made up the “Holocaust by bullets” in Ukraine and the Eastern Front.

While the Holocaust was planned by German Nazis, Ukrainian collaborators helped.

When Nazi Germany invaded the USSR, the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), a fascist organisation from western Ukraine led by Stepan Bandera and Andriy Melnyk, accompanied Nazi troops into Ukraine. And, OUN collaborators facilitated massacres of Jewish people on the road from Lviv to Kiev and beyond.

Like the German Nazis, the OUN fascist ideology equated Jewish identity with Bolshevism, a false antisemitic shibboleth.

From 1941, OUN Auxiliary Police and other armed formations facilitated the Holocaust across Ukraine, as willing and enthusiastic accomplices of the Nazis. Historians agree that without collaborator help, the Nazis could not have succeeded in mass murder on this scale.

But Babi Yar also has huge contemporary significance.

In July 2021, Ukrainian filmmaker Sergey Loznitsa won the Cannes Film Festival best documentary award for his film Context.

Context depicts the buildup and aftermath of the Babi Yar massacre using remastered black and white archival images, Thus, the 1941 Kiev events appear fresh and current. Amidst devastation, people shuffle and glance at the camera in images that could well have been recorded today.

Babi Yar is a focal point for Ukrainians today, as we engage with the past.

There are reasons for optimism.

A museum is underway to commemorate Babi Yar as a pivotal Holocaust event. Antisemitic rallies denying the Holocaust have been banned in Kiev. The Ukrainian President, Volodymyr Zelensky, is proudly Jewish, as is the mayor of Kiev, former boxer Vitaliy Klitschko. Ukraine has a religious centre for Lubavitcher Orthodox Jews in Uman. In many ways, modern Ukraine strives to reassert its historical diversity.

Tragically, some Ukrainians still struggle to recognise the full tragedy of what happened during the Holocaust in Ukraine. Although some seven million Ukrainians fought Nazism on the Allied side during World War II, and the majority of Ukrainians today celebrate the liberation of Europe from Nazi rule in May 1945, there are problems.

For an ultra-nationalist “Banderite” minority of Ukrainians today, the Holocaust is seen as part of the battle against Soviet Russian oppression.

Controversially, streets have been renamed in honour of Holocaust perpetrators and Nazi collaborators. And disturbingly, today, small numbers of Ukrainians also celebrate Nazi collaborators who fought against the Allies on the German side.

While the past is complex, the OUN and their accomplices have not gone through the “Kollektivschuld”, the notion of a collective responsibility attributed to Germany and its people for perpetrating the Holocaust, and other atrocities during World War II. For this reason, the OUN is rejected by the vast majority of modern Ukrainians, at home and abroad.

While electoral support for ultranationalist parties is only in the two per cent range, these groups exert unacceptable influence on the Ukrainian state and security apparatus. As a consequence, red and black banners, torchlight rallies, and fascist symbols too frequently feature in international news reports about Ukraine.

The current military conflict with Russia has also attracted international neo-Nazis to Ukraine. Recently, a former Australian soldier, Conor Sretenovic, reportedly tried to join the fascist Banderite AZOV Battalion. His passport was cancelled by the Australian government after ASIO advice that he and AZOV may pose a national security risk.

There are Ukrainian ultra-nationalists who live in Australia in 2021, some of them the children and grandchildren of the Ukrainians who collaborated with Nazi Germany during WWII. And some have ties with extreme ultra-nationalist and antisemitic minority groups active in Ukraine. Their denial of historical truth and glorification of Nazi collaborators as heroes, while odious, is very real.

The Australian Ukrainian Congress oppose their views, and we actively assist Australian authorities in monitoring their activities.

Today, most Ukrainians in Australia and Ukraine solemnly commemorate the 80th anniversary of Babi Yar as a Jewish Holocaust tragedy. This anniversary is an opportunity to challenge those that seek to excuse Nazi crimes and to whitewash historical truth.

We Ukrainians say, “Never again!”

Olga Proskurnyak is a member of the Presidium of the Australian Ukrainian Congress. She is originally from Odessa and now lives in Sydney.

comments