Let the artefacts speak

'It grounds them in a particular moment at a particular time'

We regularly hear the question: How will we educate about the Holocaust once survivors are no longer here? As we approach Yom Hashoah, the day we stop and remember the Holocaust, we do so with fewer and fewer survivors in our midst.

Yet this question is ironic, especially around the time of Passover, and following the festival of Purim, two days of observance where Jews famously tell and retell two incredible stories about centuries-old attempts to annihilate the Jewish people.

Let me answer the question, not with a question, but by describing a scene, repeated each weekday at our museum.

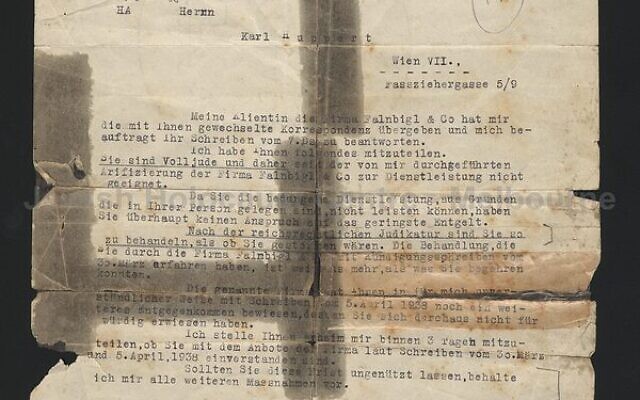

A group of 15-year-olds huddle around a piece of paper, discussing its meaning. The words are in German, but they have a translation to help them. “Who is Karl Huppert?” they wonder. Why is his lawyer telling him that his dismissal was not, in fact, unfair? The answer they discover is shocking, sent to Mr Huppert by an Austrian lawyer in April 1938, just one month after the Nazi invasion: “As you are Jewish, you should be treated as if you died.”

One month after the Nazis invaded Austria – relatively few Jews had been murdered. This letter gives us an understanding of the utter despair of Austrian Jews at this point, fearful for their future. According to the law, Jews were already considered dead.

The letter from the lawyer, however, survived to clearly tell us something important.

The students learn in school about the introduction of discriminatory anti-Jewish laws as an abstract concept.

Seeing the words on this piece of paper, and thinking about Karl Huppert, and what it must have been like for him to read those words, written by a legal authority, is very powerful. For some, it is unforgettable, moving from the abstract to the particular. It grounds them in a particular moment at a particular time.

And to demonstrate to students the nuance of history, they also study another letter of dismissal, this one for a Jewish woman in Berlin, Gerda Urbach. She was dismissed from a government travel agency soon after the Nazis came to power in 1933. Her dismissal clearly states that it is solely because of the new (discriminatory) laws and attests “her service was exquisite”. A glowing reference is also attached.

With this document we invite the young enquirers to consider: What happens in society when a new regime takes hold? Does everyone in that society agree with their edicts? And importantly, what can people who object to these new laws actually do?

The young visitors studying these documents and other artefacts are among 20,000-plus students who come each year from Victorian high schools to the Melbourne Holocaust Museum to learn about the Holocaust. And with the opening of our new museum this number will keep growing, and with education centres and museums opening across the country, the opportunity for every Australian school student to be exposed to the lessons of the Holocaust increases.

Students still meet survivors onsite – and that experience of meeting them and asking them questions remains a most meaningful opportunity – but this close encounter with the evidence in our “In Touch with Memory” program powerfully demonstrates the potential of artefacts to “speak” about what happened.

The Gandel Holocaust Knowledge and Awareness Survey (2022) revealed that 79 per cent of students who learned about the Holocaust at school agree or strongly agree that these lessons had a lasting impact, and we could surmise that this figure would be even higher among those whose school lesson included a visit to a Holocaust museum.

During and following COVID, we received numerous requests from members of our community to donate artefacts, as this lockdown period provided them with a unique opportunity to open long-closed doors and start examining the dusty, decades-old contents contained therein. Papers, photographs and occasionally items passed down from ancestors, yet often with scant detail.

Now is the time for these historical items to be handed over to institutions across Australia, for these last fragments contain gems of evidence that can help others make meaning and tangible connections to past events. Now that we have a wonderful network of museums and institutions across Australia, please consider the value that your documents can bring to them in conveying the history to students.

And, further to this, we are calling on any survivors who have not recorded their testimony to come forward now so that they can be recorded.

The dismissals of Karl Huppert from his job in Vienna and Gerda Urbach from hers in Berlin, simply because they were Jewish, are just two of thousands of stories that students can discover in Holocaust museums. Real stories, revealed by documentary evidence, securely cared for in our collections.

Jayne Josem is CEO of the Melbourne Holocaust Museum.

comments