‘Memory is essential to identity’

However, our childhood memories are not just made up of our own – they are inseparable from what we heard our family recount, over and over through the years, embellished...

I think I remember Grandpa Sandor, holding me up high like I was his sunshine – but maybe it is only the photo of us like that I remember.

Grandmother Mathilde, aunties Olga, Irene, Herta, Magda were exited from my life before I had time to get to know them. These were my mother’s family and she spoke of them seldom, with pain and difficulty. I have no memories of them.

My parents had much to remember of their youth and early years of marriage – holidays in the snow and on the beach, skiing, hiking, riding, swimming – large families and many friends. I now have many photos in which I can identify and remember them. Unfortunately, many of the larger family did not live long enough for me to get to know them. Remember them.

For my parents these photos were also a sad reminder of a future as they had imagined it for themselves before the unimaginable happened.

Memories are imperfect but photos don’t lie.

We remember our family and friends from childhood, those that survived and were left behind, as they were then – giving them no credit for having grown up and changed in the many years since we saw them – as we are forced to recognise that we have changed.

Not so long ago it was thought that children’s earliest memories start around three years of age.

More recently that has been revised to as young as five or six months old.

However, our childhood memories are not just made up of our own – they are inseparable from what we heard our family recount, over and over through the years, embellished, embroidered, enlarged; we all have our family mythology, we have tribal memories – and each generation adds to them.

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks said: “Our identity is bound up horizontally with other individuals: our parents, spouses, children, our community fellow Jews. We are also joined vertically to those who came before us, whose story we make our own. Memory is essential to identity.”

If we were to believe the stories told by our parents, each one of us was smarter in childhood than we turned out later, and their grandchildren are smarter still!

There are short-term memories, long-term memories, sensory memories, topographic memories, working memories, ageing memories, forgettable memories.

Fallible memories.

Memories are also filtered, invented, quarantined, implanted.

We all carry with us memories of the past – people, things, places, adventures – lost in time but not in memory.

We have memories of the years of childhood, parents, family – yearning for those we now miss, and time lost, perhaps a childhood never had, maybe misspent.

Memories of opportunities not taken, decisions we wish we had not made, regrets.

“Memory makes us who we are,” wrote John Locke, the English philosopher 400 years ago.

Today, increasingly a digitalised memory, which is more reliable in many cases.

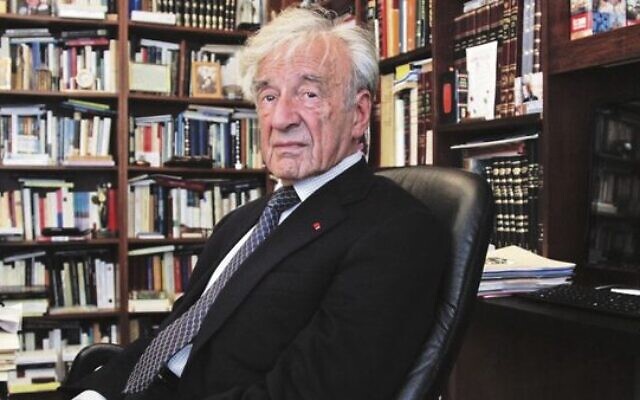

Elie Wiesel said: “Without memory there can be no culture, no civilisation, no society, no future.”

Remembrance of the past is not necessarily the remembrance of how things really were. Some truths of our past are too difficult to accept and alternate versions are created for our comfort.

Some of us remember several families who could not settle when they came to Australia because it was so much better back home – and back they went – and returned here again because back home was no longer the way they remembered it.

For some it was necessary to perform these voyages back and forth several times before they settled for reality.

Who has not indulged in wishful thinking, longing for the imagined, the irretrievable?

On a lighter note, Mark Twain observed: “A clear conscience is a sure sign of a bad memory.”

And Abraham Lincoln noted: “No man has a good enough memory to be a successful liar.”

Many of us have packed up our memories and brought them with us – to a new land or just to a new age – as if we needed, or had a choice to follow Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s advice: “Own only what you can always carry with you. Let your memory be your travel bag.”

Our memories are the last to go – when all else has faded – and so it should be.

We know that we can, and should, visit our memories – but we can’t live in them.

We can, and some do, remain prisoners of the past. We and our memories can stay in the darkness of the past, or we can use these memories to be the light to our future.

I do remember and will never forget that I am here because of the moral strength and conviction, courage and sacrifice of Jan Kraus and his family, Ivan and Marienka Brinza, ordinary people capable of extraordinary acts of bravery.

They did what they did, not for certificates, citations, awards, rewards or medals, but because they knew it was the right thing to do in that moment of our need.

And lastly, we should leave only good memories behind us.

Peter Gaspar is a child survivor of the Holocaust, and a Courage to Care and Melbourne Holocaust Museum volunteer.

comments